Note: This adventure takes place in an area of active industry filled with all sorts of hazards. I had a local guide to keep me safe – please don’t try to find your way here on your own!

A fellow adventurer hit me up one dreary July day, turns out he’d arranged a most exciting adventure. A local guide had offered to show him a historic listed lime kiln that would usually be out of bounds – and I was invited! The old kiln wouldn’t be the only exciting thing we’d see that day, but I won’t spoil the surprise for you.

We accordingly set off up the northern motorway on the scheduled day, turned inland at Palmerston and continued until we reached the town of Dunback. There we briefly admired the historic Dunback Inn before meeting up with our guide, whose much-battered 4WD carried us westward toward the looming Razorback Range.

I don’t think I’ll ever get used to how quickly New Zealand reverts to wilderness as soon as you leave the beaten track. The mountains here are bald and grim, clad in tussock and speargrass, though Ngai Tahu Forest Estates plan to convert 890 hectares of these slopes into pine plantation. Some locals are unimpressed at the idea that the stark bare ridges and valleys that they love might be transformed into tidy pine plantations, but on the other hand this plan is part of a larger effort by the forestry giant to offset dairy farming emissions by establishing 6500 hectares of pine forest. This will help New Zealand meet her obligations under climate change agreements, and I’m sure it helps that this venture should eventually net a tidy profit.

Once again the values of heritage, industry, ecology and the public vs private senses of ownership are pitted against each other.

We wended our way up what began as a steep gravel road and in the end became little more than a pair of shallow ruts, all the way to the rim of the mount that overlooked the modern lime works on one side, and plunged down into the active quarry – tidily hidden from view of the highway – on the other.

After admiring the Shag Valley up and down, we clambered back in the vehicle and made our way back down past the huge open pit of the quarry. This I believe is the “new face” opened up in 1952 while the workings were under management of the Milburn Lime and Cement Company, whose holdings included cement works at Pelichet Bay (Now Logan Park) and Burnside, and lime works at Milburn and on the Otago Peninsula.

Then we pulled up at a plateau not far below the quarry, where our surprise awaited. Perched on the shoulder of the mountain was a cluster of derelict industrial buildings, surrounded by scattered debris.

This could only be what remains the primary and secondary crushers built adjacent to the new rock face in order to crush boulders of up to 76cm cubed into a more manageable 2cm size before transport down the mountain. At least, that’s what history says. My imagination preferred to think that we’d been transported to the ruins of Chernobyl or some similar site of Eastern European decay.

We found the remains of an old forge and a concrete pad overlooking the lime works below, where once we might have found the proudest feature of this state-of-the-art facility – the aerial ropeway, said at the time to be one of the largest in the South Island. This consisted of “thirty-seven carriers filled semi-automatically from a storage silo near the quarry”, each carrier bringing 660kg of stone to the works below.

We could still see the remains of some of the supporting towers below, the tallest of which would once have been 21 metres high.

The cost of the ropeway alone was more than 2 million dollars in today’s money.

I couldn’t find any mention of the site’s abandonment in my usual sources, so had to rely on oral history instead – our guide reckoned it had gone out of usage back in the 70s, although it’s also possible that the closure of the Burnside Cement Works in 1988 also spelled the end of this crushing plant.

We continued downhill, where not far from the modern lime works we found the shed and machinery that had once formed the terminus of the aerial line, with its “automatic tipping device”.

But the area’s far more humble industrial beginnings were also represented here, tucked into the cliff below in the form of three dark tunnels.

These are the legacy of the very first attempt to exploit the lime deposits in these hills, under the auspices of the Government’s Public Works Department. It was our old friend John McKenzie who managed to obtain this power in 1897 as part of an amendment to his Settlements Act Bill. The bill also allowed a railway to be built for the purpose of transporting the lime to customers, who were offered free carriage for up to 100 miles.

It’s not known for certain whether these are the original coal-fired kilns which commenced operation in 1898, or gas-fired upgrades put into use once the coal was found to be too inefficient.

Unfortunately the troubles didn’t end there, for in the process of improving the kilns an embankment collapsed and killed three workers. Even after completion the venture remained unprofitable, and so the government offered it up for lease.

It was taken up by James Gibson for a while, until in 1909 the aforementioned Milburn Lime and Cement Company took over, immediately commissioning a state-of-the-art gas-fired Schmatolla kiln.

This steel-girded brick edifice was 22 metres high when constructed, and still perches proudly overlooking the modern limeworks despite losing a brick or two over the past century.

Looking at it up close, we could see the complex system of vents and chambers and inspection holes which allowed the kiln to process up to 30 tonnes of lime per day, whereas the old type could only manage six.

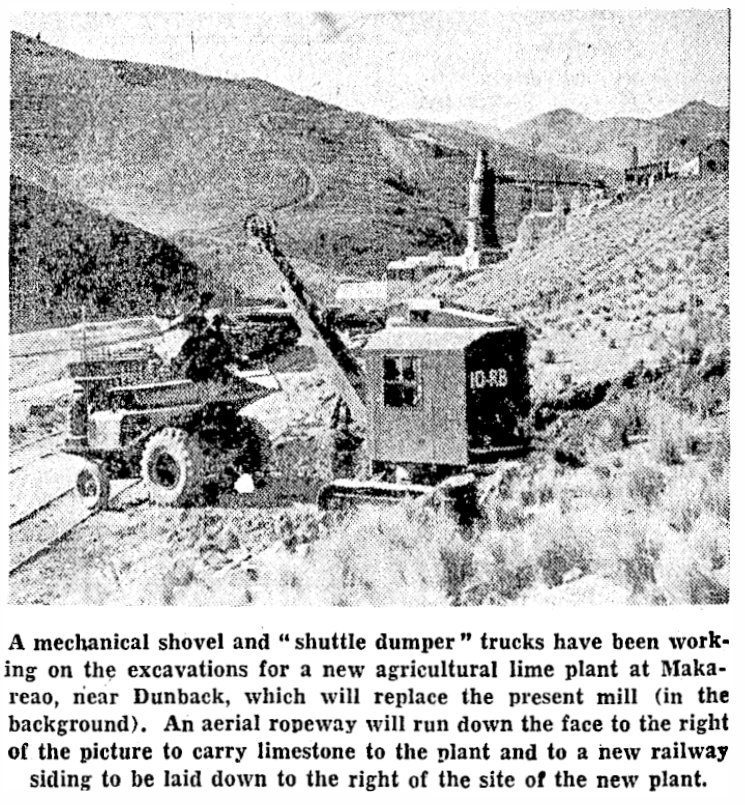

Sadly the workforce would once more pay a heavy price for progress. Two men were blown from a trestle while constructing the bridge between the kiln and quarry. One died while the other made a lucky escape with only minor injuries. The accident can be more clearly understood upon seeing the image below, dating from the 1952 redevelopments, in which the bridge can be seen in the background.

These developments also required an increase to the community residing here, with the installation of new single and married men’s quarters. The Company even provided a swimming pool, the concrete foundation of which now stands alone in an empty field.

The lime taken from here was used (unburned) as a fertiliser to increase the yield of our agricultural lands, or (burned) in the concrete produced at Burnside. In that respect it played an invisible but very literal role in building our province, including Roxburgh Dam. Today the plant supplies lime for the nearby Macraes gold workings.

In 1963 the Milburn Company merged with the New Zealand Cement Company to form New Zealand Cement Holdings Ltd, which in turn became Milburn New Zealand Ltd. In 1999 Swiss company Holcim gained full ownership. In 2015 the lime manufacturing business was sold to Graymont, which is based in North America and is the third biggest lime manufacturer in the world.

Putting together everything we’d seen at this remarkable site offered us an almost continuous picture of the Otago lime industry from 1898 until today, from its troubled government-sponsored beginnings, to its impressive heights in the 1960s and 70s, right up to its present day incorporation into a globe-spanning corporate entity.

And so this century old industry enters a new era as our landscape and our society continues to change around it. As the years pass, will this palimpsest of industry be layered once more with new state-of-the-art technology, or will it fall into disuse and finally be left behind one day as progress marches on?

References:

Ngai Tahu Forest Estates Makareao RC Application to WDC 31 October 2017The Cyclopedia of New Zealand [Otago & Southland Provincial Districts] The Milburn Lime And Cement Company, Ltd

NEW ROTARY CEMENT MILL FOR BURNSIDE Otago Daily Times, Issue 27526, 21 October 1950

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. Star, Issue 6050, 11 December 1897

LOCAL AND GENERAL. Evening Post, Volume LV, Issue 47, 25 February 1898

LIME DEPOSITS Otago Daily Times, Issue 19066, 11 January 1924

North Otago Times, 1 September 1910

MILBURN LIME & CEMENT COMPANY Otago Daily Times, Issue 15107, 1 April 1911

New owners visit Makaraeo lime works by Bill Campbell

Another great historical write-up. I think part of the issue that residents have with a pine forest will be the “wilding pines” they will all have to deal with. Sometimes growing exotic trees is not a good idea.

Planting pines to offset dairy makes no sense. “The extra monoterpene emissions from our pine forests, they augment the lifetime of methane … by probably in the order of two to three years,” he told RNZ, “he” being Dr Jim Salinger. At: https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/397692/pine-plantations-extend-lifetime-of-methane-in-north-island-atmosphere (My OH is a landscape architect/ecologist and helped me with this info.)

Amanda – Inchvalley lime kilns – I’m intrigued by the photo of the old limekiln hearth from outside – the really “tidy” arch with a loganberry bush in fruit? overhanging.

Is this one of the three kilns in the face just up the valley from the Schamiolta kiln – if so I do not recognise it. Can you e-mail me a few more pics – maybe looking down on it – I do not recognise the lay of the site nor the fact that trees are growing in the mouth of the kiln.