I’d seen where my ancestors the Parsons first stepped on to New Zealand soil, but that was just the first piece of a much larger puzzle. What were the circumstances that lead up to that brave first step? What could have possessed this little family to leave their homes and set out across the sea to begin their lives anew in an obscure colony on the literal other side of the world?

To answer that question we have to go back to the Cornwall of the early 1800s, which along with Devon was the primary source of candidates for the New Plymouth settlement. Following the end of the Napoleonic Wars an economic depression hit the region, and was especially severe in the north-east where my ancestors the Parsons lived. It was into this environment that John Parsons and Grace Gilbert were born, both children of labouring fathers.

They married in 1836 at St Denis, North Tamerton, having three children over the next five years (though the first appears not to have survived). John was an agricultural labourer, a class of person heavily affected by the high rents, high taxes, and scarce employment that accompanied the depression. The “hungry forties” now loomed, a decade in which some poorer families even faced starvation.

On 25 January 1840 a group of Devon and Cornish “gentlemen”, led by the Earl of Devon, agreed to form the Plymouth Company of New Zealand. Its aim was “to render available the resources of Devon and Cornwall, and to present to their inhabitants the means of participating in the favourable prospects offered by this new field of colonisation”.

Agricultural labourers and their families were part of the desired class of immigrants who could qualify for free passage, or purchase of land in the proposed colony could also be counted toward a subsidised passage.

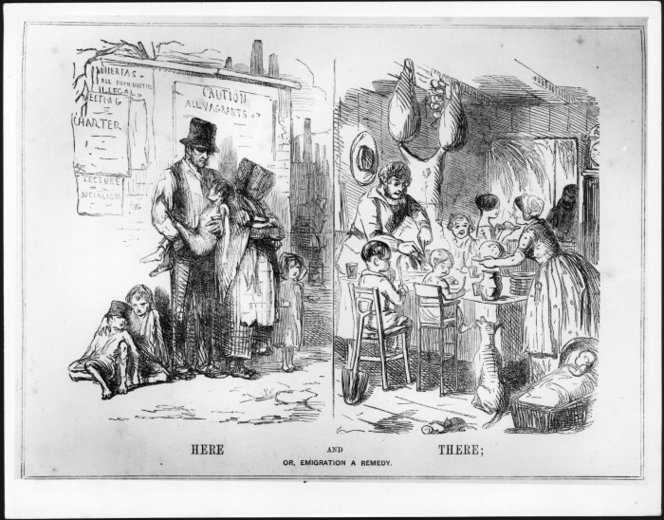

Faced on one hand with promises of abundant employment and the possibility of becoming independent land owners, and on the other scarce work and limited social mobility, emigration may have seemed like the only viable option for the family. So they became tiny molecule in the 250,000-strong tidal wave that left Cornwall for foreign shores between 1815 and 1920, in what has been called “the Great Emigration” or “Cornish Diaspora”.

In late 1841 the young couple, along with their daughter Jane and infant son Thomas, boarded the Timandra, fourth of the six ships that would carry a total of about 800 settlers to New Plymouth. At 2pm on November the 1st, 1841, the ship weighed anchor and departed. The little family would never again set foot on Cornish soil.

Lucky for us, an account of the journey has been preserved in the journal of Josiah Flight, one of the cabin passengers and later Resident Magistrate at New Plymouth.

The Parsons, unlike Josiah, were lodged in steerage, cramped and uncomfortable. The immigrants may have been on their way to egalitarian New Zealand, but that didn’t mean old English class conflict wouldn’t become the defining characteristic of this voyage.

Not more than two weeks into the journey the cabin passengers convened to complain about the conduct of the steerage passengers, claiming that steerage was “a little Ireland or hell of swearing, filth, theft, and pilfering” . The meeting closed with a resolution to draw up a notice on conduct and to form a committee for the purpose of starting a school for the immigrants’ children.

This backfired almost immediately, with many of the steerage passengers boycotting the next Sunday service at protest in being told to keep off the coveted poop deck (the rear most and highest deck of the ship). They also felt the school to be “interference” by the cabin passengers, with one representative pointedly observing that they “only wished to have the credit of conducting the school whilst the others did all the working part”.

The first death on board was of a three week old baby, son of Mary Ann and Peter Norman. Dr George Forbes, the ship’s physician, began to conduct an autopsy without consulting the parents, who were utterly distraught when they discovered it was happening. Peter protested to Josiah flight, who was eventually able to calm him down and allow the autopsy to proceed.

But sickness was spreading throughout the ship, and our family the Parsons were not immune to its effects. Little Jane died on the 13th of December after a few days’ illness. Dr Forbes was determined to conduct an autopsy on her as well, but John and Grace adamantly refused. This may seem a little odd from our modern perspective, but the Parsons came from a world in which dissection after death had long been associated with criminals and paupers, people whose families could be forced to surrender their loved ones’ bodies and forego a proper religious burial. To have their beloved daughter placed on such a level must have been enormously distressing for the grieving parents.

The Plymouth Company had problematically instructed it’s ships’ doctors to perform autopsies whenever possible, which was against the norm at the time. The steerage passengers rallied around their own and in the end the bereaved parents had their way. Jane Parsons was committed to the deep without suffering the indignity of an autopsy.

Two days later eighteen year old Mary Ann Norman died. Peter Norman had first lost his son, and now he was losing his wife to complications from her pregnancy. Dr Forbes again insisted on the necessity of a post-mortem, but Peter refused and again all of steerage rose up. This time it looked as if things might become violent before the captain backed down, and Mary Ann too was buried at sea with body and dignity intact.

No further autopsies were attempted. Soon after this drama, the Timandra stopped at Cape Town, where the immigrants were able to go ashore and take advantage of the cheap wine, which helped to lower the tensions on board.

Tempers did flare once more however over another fun little regulation by the Company – this time requiring that chloride of lime (a disinfectant similar to bleach) be sprinkled around the beds in steerage. But the immigrants feared it was damaging their clothing, so tried to stop the crew member responsible. This resulted in a fight between the sailor and one of the immigrants, Samuel Joll. The outcome was that the captain mustered the passengers and issued an ultimatum: Samuel could either apologise, or he could be put in irons until he was willing to apologise. The stubborn Samuel refused and – much to the dismay of the steerage passengers – Captain Skinner was true to his word. Samuel eventually had a change of heart and was released.

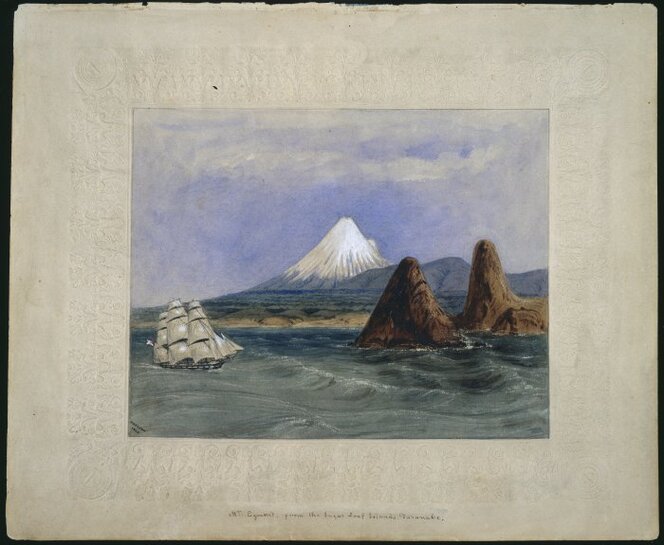

Finally, on 22 February 1842, Mount Taranaki (then known as Egmont) was spotted, and I imagine few on board felt regret that the troubled voyage was soon to end. After 113 days at sea the Parsons had now arrived at their new home, landing in the colony’s whale boat somewhere near where the wind wand now stands.

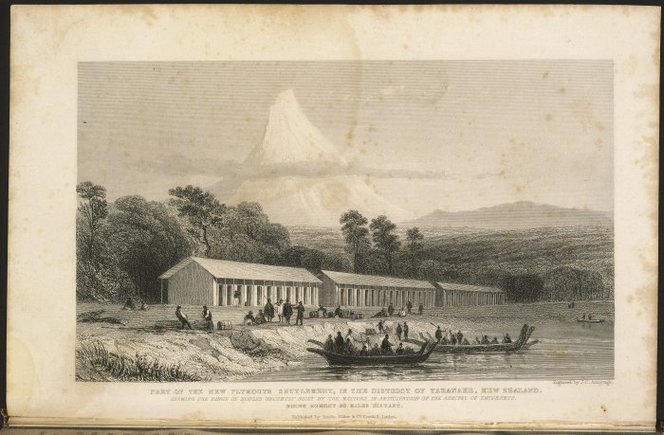

I often wonder what their thoughts must have been at this moment. They had given up everything and even lost a child in the process of coming here. First impressions were likely pretty grim. Delays in surveying the town meant that most settlers were still in tents or raupo huts ensconced on the narrow strip between impenetrable forest and roiling sea. The constant rain seeped into the makeshift accommodations, and the odd earthquake only added to the unsettling strangeness of it all. While the local Māori were friendly, there were regular rumours that war might break against their Waikato enemies.

Trade ships were reluctant to approach the dangerous exposed coast, and food shortages had brought the colony to the brink of starvation more than once. One disillusioned settler described the harbourless town as being like a “penal settlement”, seeing as it was impossible to leave or communicate with the rest of the country.

Worst of all, they had arrived in the midst of a plague of rats. A great migration was travelling south along the coast, destroying food, crawling over beds as people slept, and even attacking babies. This was on top of the usual fleas and swarms of sandflies that left children covered in red welts.

At least the New Zealand Company (which, due to financial issues, the Plymouth Company had now merged into) kept its promise to provide employment, right? It’s true the colonists were all provided with employment upon arrival, but there was more than one catch. The Company was the only employer, giving its employees very little bargaining power when it came to wages or conditions. These were fairly decent at first but became steadily more restrictive as the Company’s financial situation began to falter.

Payment was in the form of cheques on the Union Bank, rather inconvenient to cash with the institution being 180 miles away in Port Nicholson, and in consequence the cheques became a de facto currency of the settlement.

In spite of these challenges, it was hard to deny that the place was beautiful and the land fertile. The newcomers admired the clear waters, elegant tree ferns, and tame bird life. There was potential here, enough to hope that with enough hard work this struggling settlement could be transformed into a thriving and prosperous New Plymouth.

Would the little family’s big decision be worth the cost? They must have wondered as they stood on that bleak shore. Unable to go back, their only choice was to forge ahead with their new lives and make the best of the result…whatever that might be.

References:

Emigration from Cornwall in the 19th Century by John Biggans

The Establishment of the New Plymouth Settlement in New Zealand compiled and edited by J. Rutherford and W. H. Skinner

Popular Protest in Early New Plymouth: WHY DID IT OCCUR? by Raewyn Dalziel

Image Attributions:

Punch: Here and there; or, emigration a remedy. London, 8 July 1848.. Ref: PUBL-0043-1848-15. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/23241802Ship Timandra. Ref: PAColl-2200-1. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/23107244

Heaphy, Charles, 1820-1881. Heaphy, Charles, 1820-1881 :Part of the New Plymouth settlement in the district of Taranake showing the range of houses recently built by the natives in anticipation of the arrival of emigrants. Mount Egmont 30 miles distant. Engraved by J. C. Armytage. London, 1843. Ref: PUBL-0048-01. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22661554

Heaphy, Charles, 1820-1881. Heaphy, Charles, 1820-1881 :Mt Egmont, from the Sugar Loaf Islands, Taranake 1849. Ref: A-145-011. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22717831

Hi there. Great writing. I am related to the Wills and Jordan families who travelled on the Timandra.

I have just read on FB about a book about to be printed re the voyage of another family in case you are interested.

You need to pm Jo Madden to pre order if you are interested. I will try to give you the page from FB.

Thanks

Jo Madden is a member of the Taranaki Families – Genealogy and DNA FB page. You will find her on there.

Copied from her FB but didn’t have a share option. So here goes!

PRE-ORDER YOUR COPY NOW!!!!

For the Flight family it would be the very last time their feet would ever touch the hallowed ground of Queen Victoria’s England as they headed to a new colony in a land thousands of miles on the other side of the world.

This is the true story of one of New Plymouth’s pioneering settler families as documented in the historic diaries of their lives. Throughout their epic sea voyage and the ensuing turbulent years they strive to forge their own niche in their adopted antipodean home.

My book is complete and ready for printing so private message me within a week if you want to pre-order a copy so I have an accurate idea of my print run size. Will cost NZ$28.95 plus any postage required.

I’m related to the Parsons as well,

Great to hear from a distant cousin! If I may ask, which of their children are you descended from?

I am descended from their daughter Mary-Sarah (her married name is Nicholls) https://www.geni.com/people/Mary-Nicholls/6000000024726267675 my mother Elaine is studying our family ancestry, and I got to hold Thomas Parsons medal at the Puke Ariki in New Plymouth given to him in the 1860s,

Since we are family by descent, I will give you my email address, hotsugar888@hotmail.com, My name is Emily and I live in Dunedin, the same city where Mary-Sarah is buried,

I am also descended from Mary parsons and Frederick Nicholls. Funny thing is I married a Parsonson!

My dad was raised in Waimate by Mary’s grandson.

My ancestors came out about that time on the Timandra.

Clare family.

Is there a ship’s manifesto / passenger list available so I can check if it was the same voyage. Thanks.

Regards Christine

Hello, I enjoyed reading this – my ancestors came to NZ on this ship. A 20month old Ann Northcott died on this journey too. What were the primary sources you used for this? Do you know where I can access them digitally? I have heard about the diary of Josiah Flight but can’t find where I can read it unless I go to a library to look at the physical copy in the library. Can’t seem to find it online.

Many thanks,

Chris Northcott.

Hi Chris, I had a physical copy of the diary, although I think I remember reading one online years ago. You may also be able to contact a local library to see if they can make a copy for you, if you can’t access the library yourself.

My Ancestors were also on the Timandra, the Loveridge family. Quite a large family to bring all this way. Very interesting to read of the conditions they left behind to come to New Plymouth. Thank you

My ancestors were also on the Timandra, the Vercoes. I have just arrived in New Plymouth for the first time. I can’t wait to explore. I can’t imagine how they must’ve felt when they arrived back then.