Here in Taranaki I’ve been following the lives of my ancestors. I’ve traced their journey to New Plymouth aboard the Timandra, and I have visited the site of the Battle of Waireka, where Thomas Parsons fought as a member of the Taranaki Militia, receiving the New Zealand Medal for his efforts. His father John Parsons was also drafted into the militia, but his medal medal was awarded for his actions in another fight – the Battle of Māhoetahi.

In my previous posts, I’ve already sketched a rough picture of the lead-up to the war, both on a national scale and for the Parsons family themselves. While the outcome at Waireka provided some discouragement to the Māori gathering in the south, it did not stop them from defeating the British at Puketakauere. New Plymouth was in shambles, its terrified settlers crowding the town while farms burned and fields went to waste. In these cramped conditions disease tore through the refugees, and as many as 121 died from sickness. Others were evacuated to Nelson or Auckland.

While I know that Thomas and John served in the Taranaki militia, I don’t know what became of the rest of the family at that time: John’s wife Grace and their four other children, then aged 16, 13, 11 and 9. Whether they stayed in Taranaki or took refuge elsewhere, it must have been a time of great anxiety for them. Grace only lived a few more years, passing away at age 51 of “general debility and ashma[sic]”. I can’t say for sure that the war was responsible for any of her health problems, but do wonder.

Now that we understand the situation as it stood in November 1860, let’s move on to Māhoetahi. Of course I had to stand at the site, and this one is situated in a field 10km outside of New Plymouth on State Highway 3.

This little hill certainly presents an underwhelming defensive position.

When it comes to Māhoetahi, it’s one of those cases where we only really have access to one side of the story. Pakeha writers are wont say that standing here was an act of honour-driven hubris, as the Māori combatants were not local, but Ngāti Hauā from Waikato drawn by dreams of glory. We have such language as “war-fever”, “desperate for battle”, and motivation described only as “to kill soldiers”.

It could, of course, be entirely that simple. There’s not a lot of information to be had about Te Wetini Taiporutu of Ngāti Hauā, the leader of the foray, but I’ve learned that he was an intimate member of the King Movement, which arose partially in response to the increasing rapidity of land sales in the Waikato.

In 1858, at a King Movement meeting in Ngaruawahia, he said:

I say let the [Māori] King rule on his own land and the [European] Queen on hers, and both bound by love to each other, and God over both of them…Let us have new thoughts and live in peace and quiet on our lands.

Te Wetini Taiporutu, 1858

In April 1860, following the outbreak of the Taranaki War, he commented on the situation thusly:

I have two things to say. I do not approve of murder, neither do I approve of war.

Te Wetini Taiporutu, 1860

That directly contradicts the reasoning usually given for Te Wetini’s Taranaki taua, that he wished to “kill soldiers”, which while usually given in quotes is never accompanied by an actual source.

In May, during the hui in which King Pōtatau’s flag was raised, Te Wetini gave a symbolic demonstration. He took three sticks and stuck them into the ground, one to represent the Queen, one for God, and one for the Māori race. Then he picked up the Queen’s stick and threw it away. This was interpreted as demonstrating that by carrying on the Taranaki War, the Governor had severed the relationship between Māori and Europeans. Throughout the meeting he continued to advocate support for the Taranaki Māori and an end to land sales. This was seen as an extreme position by the European commentators, but it is hardly a one-dimensional lust for battle.

Missionary John Alexander Wilson, who followed the war-party to Taranaki, recalls finding Te Wetini one of few receptive souls to his pleas for merciful conduct toward the settlers. They spoke on the day the party departed, and as he tells it the occasion was more sombre than “feverish”.

When I arrived early this morning the last files of the taua were leaving the village of Kihikihi. I found Wetini standing alone, looking at the men of his tribe as they passed before him. He seemed heavy and cast down. His only weapon was the sword of Lieutenant Brooks, which he held drawn in his hand. After we had greeted, his words were few. “We held a runanga, as I promised you,” he said; “but the people would not hear. Epiha, Te Oreore, and myself were for mercy to the wounded and prisoners; all the rest were against us. I now go with them to this war, but should they persist in this evil work and act as at Puketakauere, I shall leave them and return to Waikato.”

J. A. Wilson, Missionary Life and Work in New Zealand

With this evidence, it seems unfair to boil down Te Wetini’s motivations to “savage chivalry”, when they were undoubtedly far more complex. We’ve started to challenge long-standing European narratives regarding the New Zealand Wars, and perhaps one day a better scholar than I might bring some justice to Te Wetini.

The tale takes on a new, tragic tone when you start to consider the complexities at play, instead of treating it like a just-so morality tale with a lesson on unchecked hubris.

Te Wetini and his taua established themselves on this little hill, and this brings us to another criticism of the much-maligned Te Wetini. For what fool would set up a defense on this “gentle mound”, unfortified save for some old pre-European earthworks?

It was slightly better at the time, surrounded by perilous swamp and tangled scrub. Bringing his meagre force (the number of men is, as usual, much contested, but about 150 is the generally accepted figure) here may have been part of a larger plan, to lure the enemy out from New Plymouth into the treacherous wild land where Te Wetini’s Taranaki allies could strike from the surrounding area. To this end, he sent the following message to the assistant native secretary in New Plymouth, Robert Parris.

I have heard the word about coming to fight me, that is very good; come on the land, and let us meet each other; the sea is the place for fish to light in. Come on the land where we may stand on our feet; make haste, make haste, don’t delay. That is all I have to say to you—make haste.

Te Wetini Taiporotu

Depending on which narrative you favour, this might have been part of his strategy, or a further example of his foolish hunger for glory.

Unfortunately, the defenders were still digging in when they were interrupted by a force of Europeans, who had been sent out from the settlement on a similar mission – to secure the hill of Māhoetahi. That was the 5th of November.

The European force set out at 5am on the 6th, numbering about one thousand in all. The professional soldiers of the 65th Regiment took the middle and the right flank, while the Volunteers and Militia had the left – my ancestor John among them.

Unready, and facing 10-to-1 odds, the only hope for the defending force was to make a fighting retreat. Though the Europeans did not quite manage to surround the hill, the result was still a disaster for the Ngāti Hauā.

Te Wetini died in the retreat, and his son was injured so severely he died in New Plymouth days later. Te Wetini’s brother, Paora Te Ahuru, escaped, reportedly with a bayonet still in his body as he fled. It was also reported that Porokoru, who had co-signed Te Wetini’s challenge, was killed, but later reports suggest he lived to fight another day. If there had been a plan for reinforcements to come from the surrounding area and ambush the Europeans, they never did.

In just two hours, it was over. About 40 fallen Ngāti Hauā were found and buried right here on the hill. Six, including Te Wetini, were buried at St Mary’s Churchyard in New Plymouth.

The losses on the New Plymouth side were 4 killed and seventeen wounded. Though it was a decisive win, there wasn’t much to show for it. The Ngāti Hauā weren’t local, so the Taranaki side remained unharmed. Māhoetahi itself held little strategic value. From this point on, the strategy of the “long sap” was implemented – which you can read about from the perspective of my other ancestor, Frederick Nichols.

Beyond being present, John Parsons apparently didn’t distinguish himself in the battle. Upon approving the application for his New Zealand War medal, Captain Stapp, who had been his commanding officer, said that he “had every reason to believe” John had been there. He lived another decade before passing away at age 58. He wasn’t wealthy. He was buried at Grace’s side in Te Henui cemetery, but no headstone marks their grave.

Thus ends the story of Grace and John Parsons, whose life here is marked by a street name, a scatter of newspaper references, and a medal for probably having fought. So too ends Te Wetini, remembered more as a fable than for the complex man he truly was.

Image sources:

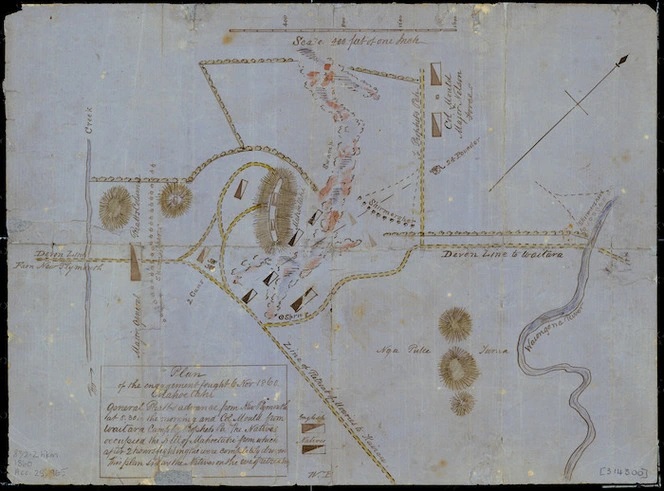

[Creator unknown] :Plan of the engagement fought 6 Nov. 1860 Mahoetahi [ms map]. General Pratt’s advance from New Plymouth at 8.30 in the morning and Col. Mould from Waitara Camp by Prophets Pa. The Natives occupied the hill of Mahoetahi from which after 2 hours fighting they were completely driven. This plan shows the Natives on the eve of retreating, [1860]. Ref: MapColl-832.2hkm/1860/Acc.25965. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22311930

References:

War in Taranaki 1860-63 ‘A change in tactics’, URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/taranaki-wars/change-in-tactics, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 21-Oct-2021

TARANAKI. New Zealander, Volume XVI, Issue 1526, 1 December 1860, Page 7

JOURNAL OF PROCEEDINGS AT WAIKATO. Taranaki Herald, 11 June 1860, Page 1 (Supplement)

Missionary Life and Work in New Zealand by J.A. Wilson

The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period: Volume I (1845–64) by R.E. Owen

Narrative of the Late War in New Zealand by R. Carey

The Maori king by J.E. Gorst

MAIL NOTICE. Taranaki Herald, Volume XIX, Issue 1091, 24 May 1871, Page 2