Heading south through the Marlborough district on State Highway One, I had a special place in mind. An unassuming pull-off at Tuamarina, not far north of Blenheim, boasts a significant place in our history. Here in 1843 Māori and European faced off in the first battle of the New Zealand Wars, and the only one to take place in the South Island.

The seeds of this “affray” (as they refer to it these days) were sown in the London office of the New Zealand Company, where Edward Gibbon Wakefield threshed out out his high-minded plan to create a colonisation scheme that instead of marginalising the “natives”, would integrate them into the new society and carry them forward on the wave of “civilisation”. The scramble for New Zealand land – they had to get here before the fledgling Government laid down the law regarding purchases, before competing colonisers, and before Sydney speculators – meant he sent his brother Colonel William Wakefield off in a hurry, but not without principled instructions on the purchase process: honesty and transparency were key, with the vendors understanding clearly what they were giving up and what they were receiving in return. By November 1839 he had purchased about 20,000,000 acres in the North and South Islands, centred on Cook Strait.

Predictably this enormous land haul did not go unchallenged, both by those who had already purchased parts of it and by the Government. Nevertheless they pressed ahead with their schemes, promising every colonist a certain acreage of land, even though it would quickly turn out that the Nelson settlement did not contain nearly enough arable land to go round. This soon got the New Zealand Company in dire straits as colonists abandoned the settlement or threatened to riot.

Over the Richmond Range, on the other hand, the wide fertile plains of the Wairau Valley beckoned. The only hitch was that Te Rauparaha steadfastly denied that the Wairau Valley was part of the land signed over to the New Zealand Company. But the Nelson Examiner reasoned:

God ordered and made the law…that man should work, and that the right of property be given by labour expended…and that all the chaffer about rights of the natives to land, which they have let lie idle and unused for so many centuries, cannot do away with the fact that, according to this, God’s law, they have established their right to a very small proportion of these islands.

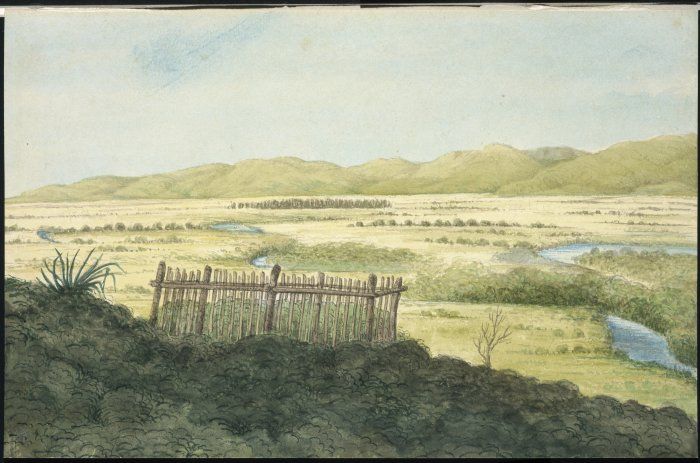

So when the chips came down the high ideals upon which the Company was founded were dropped in favour of the slightly less meritorious but ever-popular philosophies of “you snooze, you lose” and “God says so”. The overseer of the new settlement, another Wakefield brother by the name of Arthur, sent surveyors out at the start of 1843 – which brings us to what we see here at this little nook just off State Highway One.

A stone cairn stands, erected on the 1959 centennial of settlement in this district. One plaque pays tribute to the first settlers,and another to the first survey team, indicating the location of their camp (on the slope of the hill behind, now whittled away for the railway cutting). It certainly doesn’t mention that either of these things were contested.

But contested they most certainly were, and Ngāti Toa immediately protested this incursion into their land. Te Rauparaha’s older brother Nohorua led a delegation to Nelson to but was rebuffed by Arthur Wakefield, a second party which included Te Rauparaha and Te Rangihaeata met with a similar result and was denied the opportunity to use the Land Claims Court to settle the dispute. Upon being threatened with arrest, the delegation left, but not without Te Rangihaeata’s ominous warning that any surveyor that returned to the Wairau would be shot. A third delegation, consisting of younger, Christianised Ngāti Toa were also rebuffed.

Te Rauparaha was fairly elderly by this point, which made it easy for Arthur Wakefield to dismiss him as “a terrible old villain” who was “all bounce”, and his followers as “drunken travellers disturbing the peace”. Perhaps if he’d known more about the old chief’s history – his conquest of the top of the South Island, his sacking of Kaiapoi Pa, and the great mana he commanded – he might have reconsidered his stance.

So Te Rauparaha and Te Rangihaeata travelled to the Wairau themselves and escorted the surveyors off the lands, burning their huts behind them. Arthur Wakefield, with the assistance of Nelson’s temperamental Police Magistrate Henry Thompson, reacted to this by issuing a warrant for the arrest of the two chiefs and gathering a force of about fifty untrained Special Constables, some of whom had never even handled a weapon before. This ill-fated force sailed to the Wairau and on 17 June 1843 approached the very spot I was now standing to face the Ngāti Toa force ranged on the far bank of the Tuamarina stream.

The titoki tree used as a mooring for the canoe that Arthur Wakefield and his party used to cross still graces the stream bank, behind a sign created by local school children which gives an overview of the event. Lucky for me there is now a road bridge, which allowed me to follow the conflict across the deep stream in the absence of a handy boat.

In the ensuing confrontation a shot – perhaps accidentally – hit and killed Te Rangihaeata’s wife Te Rongo. From that moment all bets were off and the far more experienced Māori force pursued the Special Constables back across the stream and up the hill behind, where a cemetery now stands. That’s where I must go to continue the story, and luckily it’s only across the highway and past the school.

Upon the hill another monument, erected in 1866, marks the approximate spot where a number of the European party surrendered, only to be executed without mercy by Te Rangihaeata for the the death of his wife and other insults toward his people. Twenty-two settlers fell, including both Arthur Wakefield and Henry Thompson, and between three and nine Māori. The surviving Pakeha fled back to the river mouth and the comparative safety of Nelson.

I say “comparative”, because the residents of the fledgeling settlement feared attack now that hostilities had been opened, with Ngāti Toa from far afield gathering to support their chiefs. The Ngāti Toa vastly outnumbered the Europeans at this time, so outright war could easily mean extermination for the infant town. Fortifications were built and militia trained to defend the settlement, while the Government declined to offer any financial or military support.

The extremely tense situation was eventually resolved by Governor Robert FitzRoy’s investigation ruling in favour of the Māori, stating that while the killings were to be regretted, the settlers had provoked the incident. Though the Nelson Examiner raged against this decision, the Māori never did attack and tensions eventually eased.

But the balance of power had shifted and Ngāti Toa, vindicated in their possession of the Wairau, became increasingly confident in asserting their mana whenua over the Nelson region. Arthur Wakefield and Henry Thompson’s series of misjudgements and poor decisions had left both of them dead and the Wairau still firmly out of the New Zealand Company’s grasp. Though no further battles were fought in the South Island, the event had profound effects throughout the country and foreshadowed further conflicts that were fast approaching.

And what of the Wairau? Today’s tale ends here, but only a few short years later the tug-of-war for the valuable district would take a new turn, a contentious one fraught with kidnap and blackmail.

But that is a story for another day.

References:

Te Tau Ihu o te Waka: Aa History of Maori of Nelson and Marlborough. Volume I: Te Tangata me Te Whenua – The People and the Land by Hilary and John Mitchell

Nelson Historical Society Journal, Volume 3, Issue 1, October 1974 Tua Marina and Port Underwood

Gnarled tree marks place of Wairau Affray by Mike Crean

Making Peoples by James Belich

Excellent post- very informative and interesting. Look forward to your follow-up about the settlement of the Awatere and Wairau Valleys.

Thanks for posting this, Amanda. I’ve grown up with this story, as my ancestor was one of the NZ Company surveyors involved in the Wairau. There have been a number of art works recently in Nelson that are bringing the significance of this event into the wider public eye.

Beautiful place, how long does it take to get there?

Do they go visit their for annual tribute?

The solemnity of the place makes it a great memorial. I hope in upcoming Christmas they will hold event there.

url:

https://www.roofingrepairstauranga.kiwi/