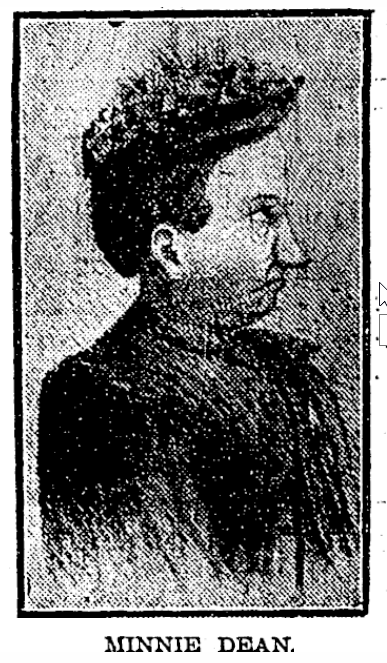

Once again it was time for a day trip to Invercargill, and once again I planned to steal away my family for an adventurous detour. This time I fixed upon a small Southland town, once home to the famous baby-murderer Minnie Dean, only woman ever to be hanged in New Zealand.

The catch was we weren’t even sure if we’d even make it out of Dunedin due the copious amount of rain and flooding over the past week. As we crested the saddle heading toward Mosgiel the Taieri Plain hove into view, and I was alarmed.

However the road was clear so we made it through the flooded fields without mishap.

As we approached Winton from the north we discovered the street where once Charles and Minnie Dean had lived with their large brood of adopted children. It seemed first and foremost to be a crossroads leading elsewhere.

I didn’t head down the road in search of their home, for a reason you’ll understand later. Instead I headed straight for the Old Winton Cemetery. Once again the others set up their picnic while I took a wander in search of my historic quarry.

The more engrossed I became in Minnie Dean’s story, the more my initial flippant assumption that this would be a fun gruesome Halloween tale faded. Like a lot of things this story is both more complicated and more tragic than first glances might suggest.

Minnie was born in 1844 as Williamina McCulloch in Greenock, Renfrewshire, Scotland. Her father was a train driver, and in the 1851 census (the only one she appears in) her family is living in a tenement shared by eight households. Father (John), mother (Elizabeth), Minnie and two of her sisters (Christina and another Elizabeth) occupied a single room apartment. Three other daughters had died young, and two more were born over the next few years.

In the 53 page statement Minnie wrote while awaiting execution, she described the ordeal of watching her mother slowly die of cancer. At first I suspected this might be another of her fabrications, as on subsequent censuses, though Minnie has disappeared, the family otherwise seems complete, including mother Elizabeth.

But a lot can happen in the decade between censuses. For example, a woman can die and her husband can remarry another woman of the same name, creating a trap for future historians. It’s a trick at least two of my own ancestors have pulled.

But the next mystery of Williamina McCulloch’s young life is not so easily solved. Despite the earnest attempts of every historian who has examined her case, none have yet discovered the answer. For the young Williamina McCulloch disappears from Greenock and does not resurface until three years later in Invercargill, claiming to be Mrs McCulloch, the daughter of a clergyman and the widow of a doctor – and with two young daughters in tow.

Her presence in Invercargill wasn’t entirely random – a maternal aunt was one of the founding settlers of the city. “Granny Kelly”, as she was popularly called, must have known that her niece’s story wasn’t true, but never gave her away.

Minnie’s explanation, and the most likely one, was that she had come via Australia. But how she got there, who she travelled with, and even whether the two children were her own or acquired in some other way are all unanswered questions.

It seems likely that the two children were her own, and illegitimate, so perhaps Granny Kelly kept quiet in order to save her niece the stigma that would accompany such facts. Here in New Zealand, posing as a sixteen-year-old widow, Minnie had a chance for a fresh start. She made a living by teaching, and by all accounts was a kind and intelligent governess.

In 1872 she married Charles Dean, keeper of the Etal Creek hotel. Charles was not a strong personality, and though he apparently disapproved of Minnie’s later activities he appeared unable or unwilling to stop them. The marriage may have seemed like the gateway to a comfortable existence, but the Deans seemed cursed by bad luck or ill judgement, or perhaps a mixture of both. Business in Etal Creek dried up as the gold rush waned and other travel routes gained in popularity. So the Deans purchased a farm in the midst of the land boom, only to fall into bankruptcy during the 1880s depression that followed.

Which brought them to Winton. They purchased a roomy home (on what is now Deans Road) known as The Larches, only for it to burn down shortly after they moved in. So Charles built a two room shack with attached lean-to which served as their home.

During this time, her two daughters grew up, married, and left home. But tragedy was not far behind, and one day in 1882 Minnie’s daughter and two grandchildren were found drowned in their own back yard well. The inquest jury (in an act of kindness to the grief-stricken husband, as suicide was considered a sin) declined to come to any official conclusion about how they had ended up there.

The marriage between Minnie and Charles produced no children, and it was at The Larches that Minnie began collecting children in earnest. Over the years an astonishing total of 28 children passed through her hands for varying amounts of time.

How on earth did one woman manage to find 28 children who were either unwanted or unable to be cared for by their own families?

Lynley Hood, in her biography of Minnie, tells of tracing the origins of 18 of those 28. Of them, 16 were born out of wedlock, and the other two were born suspiciously soon after their mothers’ marriages and disowned by the men involved. Of those whose source of payment are known, four were paid for by their mothers, five by fathers, and seven by grandparents (the standard fee for taking a baby permanently was £20).

The options for unmarried women and girls who became pregnant in Victorian New Zealand were all-around horrible. Some risked death at the hands of an illegal abortionist, some concealed the birth (itself a crime) and committed infanticide, some ended up in Rescue Homes such as the one in Caversham. Others were willing to pay for someone to remove the child – the product of their shame – and raise it as their own. And so the industry of “baby farming” sprang up, those who made a business of taking in unwanted children and accepting payment for doing so.

The idea of providing any kind of support for unwed mothers so that they could keep their children was considered preposterous – it was thought such a thing would only encourage rampant immorality.

So much for where Minnie got the children – what happened to them after? Six died, ten lived, and three went to fates unknown. One further infant was in her care only very briefly before being removed by police.

That’s not actually too bad a track record when you consider the time period, especially knowing some of these children were extremely young – even newborn. Survival odds were slim for a young baby without breast milk in an era when other sorts of milk were at risk of contamination and formula wasn’t an option.

In 1891 an inquest was held after the death of one of the children in Minnie’s care, six week old Bertha Currie. It found that the child was well nourished and likely died of natural causes, but criticised the state of the house. At the time of the child’s death Minnie had ten children total in her care, ranging in age from six weeks to eleven years. Three slept with Minnie in her bed, four in boxes about the room. Two slept with Charles in the lean-to, and two shared a bed in the kitchen.

In spite of the crowding and shabby state of the house all the little ones were well fed and cared for.

The inquest may have exonerated Minnie from responsibility in Bertha’s death, but by being published in the newspapers it brought a lot of negative attention. In future she was much more reluctant to report the deaths of children in her care.

During this time too the police became increasingly interested in her activities, and a new law, the Infant Life Protection Act, was introduced in 1893 to monitor baby farming – it required those involved in the industry to register themselves and the children in their care. Minnie never did apply for registration, believing – perhaps rightly – that she would be denied.

In spite of the scrutiny, Minnie continued to acquire children, becoming increasingly secretive in her efforts to do so. The baffling part here is why she didn’t just stop. Was it economic desperation? The business doesn’t seem to have been financially viable and Minnie was accepting children at lower and lower prices. Her behaviour has even been called compulsive. Was she then a hoarder of children like some today hoard animals? Was she trying to fill a hole left by her lost child and grandchildren? Or perhaps she felt some strange sort of kinship with unwed mothers and their unwanted children, borne from her own personal experiences?

Whatever the reason, it was to be her downfall.

In April 1895 she travelled to the Bluff to pick up Dorothy Edith Carter. In a rush to make it to Milburn in order to pick up a second child, she purchased laudanum and administered to the girl, either to calm her fretting and help her to sleep, or to intentionally overdose and kill her – depending on who you believe.

This use of laudanum – to soothe infants, not to harm them – was fairly common at the time, though even then it was known to be dangerous. Laudanum is a tincture of opium, hazardous and addictive.

Whatever the intent, Dorothy died on the journey. And here the most infamous scene of Minnie’s crimes takes place – she hid the body in her tin hat box and continued on her way to meet the woman who would hand over little Eva Hornsby.

Eva was in her care for perhaps only ten minutes – after which her body joined Dorothy’s in the hat box. Minnie claimed this was the result of a fall, the autopsy doctor suggested suffocation was more likely.

An sharp-eyed newsagent had noticed Minnie with a baby at one stage of her journey, but then no baby on another. This information was handed on to police, who traced the origins of the infant and confronted Minnie. She told them she’d never had the child, then that she was fine, just with someone else. Based on the fairly flimsy evidence at hand she was arrested for murder.

A frantic search ensued for the body, but what was unearthed in Minnie’s garden was completely unexpected. The recently-interred bodies of two babies, followed by the skeleton of a third child. These finds, reported breathlessly by the press, whipped the nation into a frenzy.

It took the jury only half an hour to find Minnie guilty of the murder of Dorothy Edith Carter. For this she was sentenced to hang. She proclaimed her innocence to the last, and her only wish was to see her children (five were removed from her home following her arrest) once more before she was killed.

So was the jury poisoned by prejudicial press and moral indignation? There’s no doubt that Minnie was a liar, and that she directly caused the death of at least one, almost certainly two, children. But was she the ruthless monster she has been made out to be, taking payment for children intending only to kill them as soon as she was able?

I for one am not so sure any more.

That was the end of Minnie, but what became of Charles? For the time period, it’s rare that a man’s life should be so completely overshadowed by the fame of his wife. Charles was found free of fault and returned to the Larches, which in 1908 burned down again, this time with Charles inside. He left no family, the papers reported.

He was buried here with his wife in Winton Cemetery.

I soon found the spot. At first the site was unmarked, though legend had it nothing would grow there. Then a headstone mysteriously appeared in 2009, but was quickly replaced by an official one laid by one of her surviving relatives. The unveiling ceremony, attended by about 100 people, focused on themes of forgiveness and reconciliation.

It’s a somewhat uplifting end to a tale that has been otherwise heartbreaking throughout. Those 28 unwanted children, presumably only a small sample of hundreds. The mother and two children found drowned in their own well. The lonely death of Charles Dean. And weaving together all these tragedies is Minnie: respected teacher, compulsive baby-collector, kindly adoptive mother, liar, murderess.

References:

Minnie Dean, Her Life and Crimes by Lynley Hood

1851, 1861 and 1871 UK Census Records, via FreeCen

The Woodlands Fatality. Southland Times, Issue 4395, 10 August 1882

Inquest at Winton Southland Times, Issue 11695, 27 March 1891

The Trial of Minnie Dean by J.O.P. Watt

Mystery headstone on Dean’s grave By Hamish McNeilly

Minnie Dean: offer of forgiveness by Debbie Porteous

Mist enjoyable read, I am left wondering winnie Dean’s is shown in such poor light’. For the money she earnt, replacing children to homes where they were wanted, and releiving girls/ women in a predicament’ brought about by ” men/bosses/abusers” she certainly never lived the ” high life ” , children died, disentry, amonst unsanitary conditions, depriving breast feed didn’t have the best start,

Great read!!! You really put a huge effort into the research and writing of your stories, well done

Thank you!