Another sparkling day off dawned upon a car-less adventurer. There was nothing to do but find another on-foot adventure, and luckily I had just the thing on my list. Almost since this blog’s inception I’ve been meaning to document the disappearing piles of St Clair beach before they are washed away and I lose my chance forever. It’s just that with so many other fascinating places to explore, I’ve so far managed to neglect this popular Instagram backdrop.

But that changes today! I strode past the fine Tudor-style houses of Forbury Road, reflecting the more English and Anglican tendencies of this suburb’s earliest settlers, in contrast to our more famous Scottish Presbyterians. Reaching the end of the road, I turned left along the Esplanade and made my way toward the golden sands of St Clair.

St Clair Beach has been the seaside destination in Dunedin since the city was founded, with thousands of early Dunedinites flocking here for sunning and surf-bathing over the hot Christmas holidays as early as the 1880s (when horse-drawn trams made the area accessible to city folk). And for almost exactly as long, there have been complaints about the disappearance of the sand, and schemes to preserve it.

The problem wasn’t just aesthetic, as dune loss caused practical problems such as when the sea breached the dunes for the first time in 1883 and flooded parts of South Dunedin.

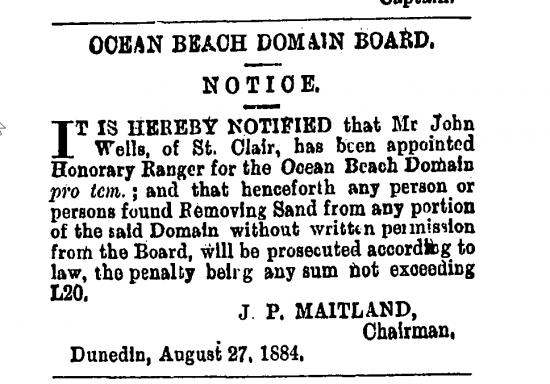

In 1884 an Ocean Beach Domain Board was constituted, charged with conserving and beautifying the sand dunes, which in many cases had been dug away or sold as lots for building on (the original subdivision of St Clair included properties that bordered the high tide mark, a situation that was bound to end in tears even in the days before climate change was a thing). However the government declined to provide the board with funds for such a mission, leaving them rather at a loss to do anything about the issue, though they did appoint a “ranger of the sandhills” (coolest job title ever?) and forbid the removal of sand – at least, not without a licence.

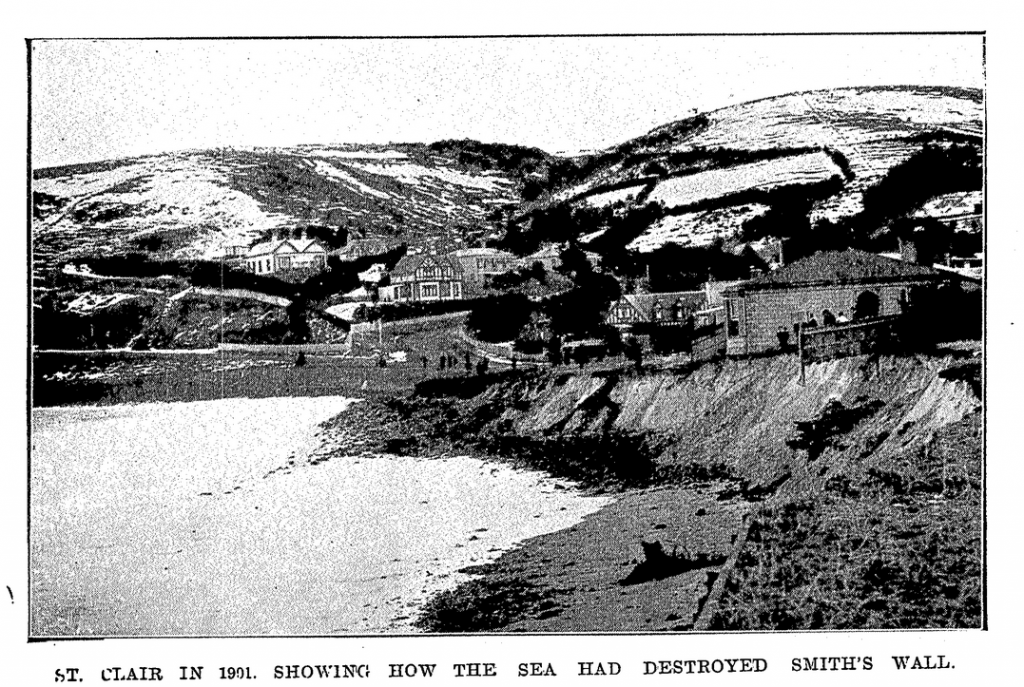

The first attempt to fight the tides appears to have been James “Darky” Smith’s privately built stone wall built in 1884 and washed away only two years later. The Caversham Borough then erected a replacement wall of rubble in 1888 but that lasted only a year. The dunes were breached in 1891 and again in 1898, this time with flood waters reaching as far as Hillside Road.

This set off a flurry of discussion toward fixing the issue, with the Ocean Beach Domain Board reviewing three proposals, including one by Francis Petre who recommended a wall at St Clair and a clay bank along the back of the dunes. It was civil engineer Leslie H. Reynolds who proposed a series of groynes as part of his solution, and argued passionately for it with several correspondents to the newspapers of the day. The third proposal was submitted by engineer and surveyor William Henry Hutchison, who irrelevantly but mildly interestingly died of a shark attack at Moeraki in 1907. After much debate (including a meeting at which mayor of the time, Edward Bowes Cargill, walked out) the matter died down and nothing was done.

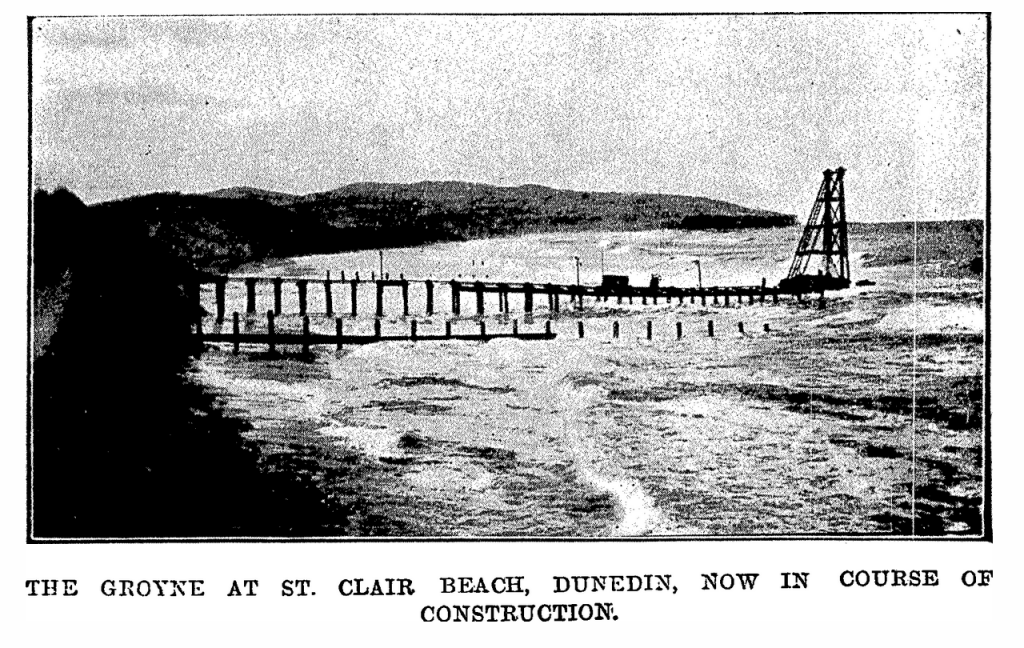

That is, until 1901, when there was a sudden revival of interest and the Board was finally given the means to raise funds for protecting the beach. The reason for this appears to have been heavy weather which occurred in 1900, the result of which can be seen in the image below.

A two-pronged approach was tabled, involving growing and stabilising the sand dunes by means of barriers and replanting coupled with raising the high water mark through the construction of groynes extending out into the ocean, which – it was hoped – would cause sand brought in by the prevailing currents to settle instead of drifting away.

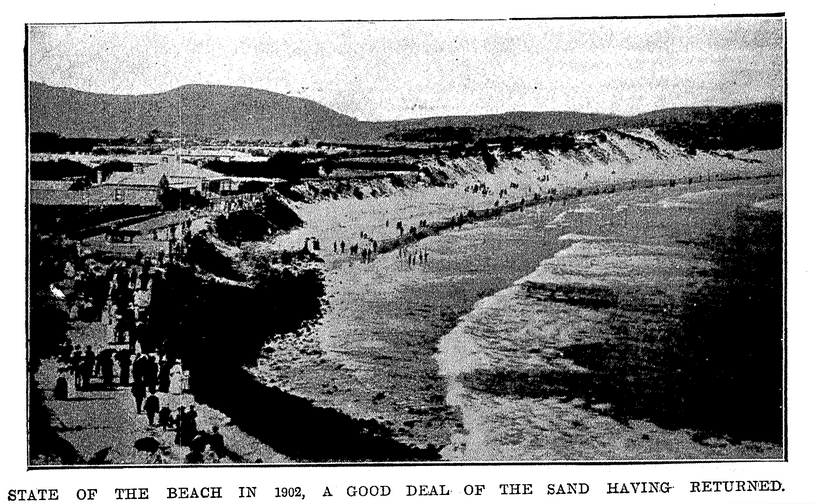

A first groyne was installed by 1903 and more put in place by 1905. At first public opinion appeared to be full of praise as sand returned – however, if you look at the pre-groyne 1902 picture below you may note that plenty of sand came back on its own.

Alas it was not to last, and by 1920 the beach was in just as sad a state as it had been in 1901. Once again, something had to be done lest the “salubrious suburb” of St Clair be completely washed out to sea. Once again, debate raged. Was the solution more groynes? Or a breakwater extending from the rocky point beneath the salt water pool? Or perhaps a barrier at the base of the dunes?

It was groynes again that were decided upon in the end, though not without some commentators calling them “eyesores” and “beach disfigurements” and describing the work as “money thrown into the sea”.

Funding delays meant that construction was delayed all summer and had to be carried on through winter, with all the extra challenges caused by stormy winter seas. As a stop-gap measure a barrier of rocks was piled against the dunes to keep them from being washed away, though some would opine this action could only make matters worse.

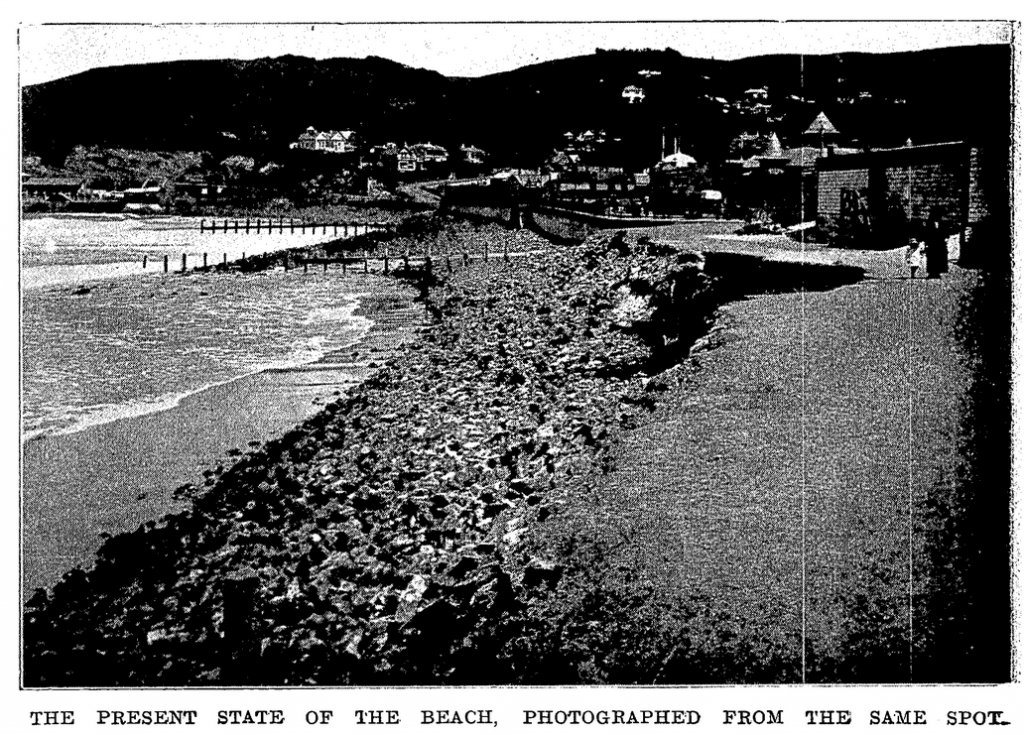

The groyne design was modified to two rows of piles, ten feet apart, upon which a tram line could be mounted to carry the necessary machinery. After that, boards would be hammered between the piles to further break up the action of the currents. Unfortunately the extra cost of the modified design meant that only three could be completed, one of them being the one so beloved by photographers in its final years.

The third and final groyne was completed in January 1921, to be immediately challenged by a week of storms in February that ripped out six of the piles and left the beach in a “wretched” state. After enduring much outrage and armchair coastal engineering from the general public, the Domain Board eventually decided to fill in one of the groynes with stone and to place an apron of rocks at the base of the Esplanade, which was suspected in driving currents up the beach to scour away the precious sand.

By 1923 the storms (both figurative and literal) seemed to have died down and sand had apparently returned, though whether the groynes actually had anything to do with it is unclear. Regardless, the Domain Board claimed it as a win.

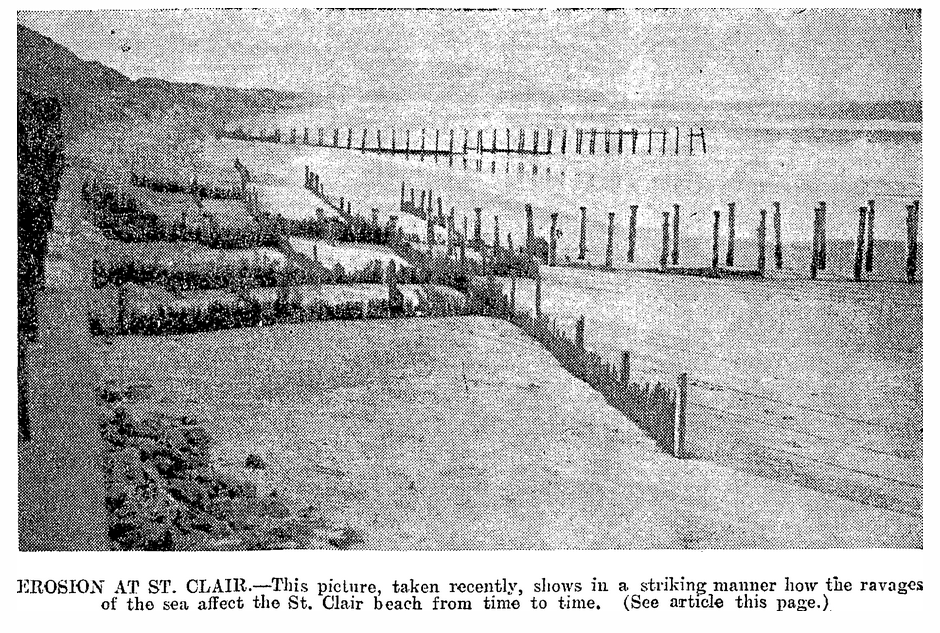

But by the mid-1930s the tides were again turning. The St Clair Surf Club argued that the groynes were nothing but a hazard, and erosion was once again ravaging the shore.

From the fifties through the mid-nineties things seem to have been uncharacteristically quiet on the beach erosion front, and I’m not sure if it’s due to the sources I checked or the fact that the Esplanade area suffered a downturn, with publicity in the eighties focusing on drunken delinquent youths, vandalism, and shabby derelict buildings. Responsibility for the area also passed from the hands of the Domain Board and into those of the Dunedin City Council when the former was dis-established in 1989.

Revitalisation came in the latter half of the nineties, with the Council providing repairs and re-paving the Esplanade, improving amenities, planting trees and commissioning art work. Businesses moved back in and the area once again became trendy.

There was only one problem. You guessed it – erosion. March of 1998 brought gale-force winds which scoured the sand out from beneath the Esplanade, undermining the cobblestones and causing large slumps to appear, as well as wrenching a staircase away from its mooring. Then in March of 1999 the sea swept away extensive anti-erosion efforts including sand and rock backfill and native plantings on the nearby dunes. One estimate put the loss at 600 cubic metres of sand.

It was at this point the Council determined that the Esplanade, built starting 1912 to replace the doomed Smith’s Wall, was nearing the end of its useful life span. Undermining and slumps were now a regular thing, costing about $12,000 per year to repair.

This set off another round of public discussion, with the Otago Daily Times running a “Saving Our St Clair” series soliciting views and ideas from readers. All the old suggestions resurfaced, like the breakwater extending out from the hot water pool, along with some new ones such as an offshore artificial reef made from tires or a pier built over the site of our single ragged remaining groyne.

This suggestion was immediately met with resistance, as one reader argued:

I adore the warped and wizened shapes of that old thing. It’s nature’s sculpture, made of natural materials by natural forces…

The Council eventually narrowed it all down to three plans: 1. Rebuild the Esplanade wall to its original position and height. 2. Replace it with a series of wide terraces leading down to the beach. 3. A split level design with vehicle access and a slightly lower promenade for pedestrians.

I don’t want to spoil the ending, but one of those does sound mighty familiar.

When the time came for the Council to seek consents the public was perturbed to learn that they had also slipped in a 20 metre long rock groyne jutting out from the Salt Water Pool. The controversial groyne was the only part of the massive $6.06 million project not to receive approval.

Construction began in October 2003, as the existing sea wall was covered over by 280 5-tonne concrete panels, in a saw-tooth configuration designed to help deflect the waves.

The work also included installation of “riprap” boulders bolted to the rocks by the Salt Water Pool to calm the surf, reclamation of a small amount of land between the Esplanade and Salt Water Pool, and stabilisation of the dunes using geotechnical bags – or as we might call them: “sand sausages”.

The project was completed in November 2004, and the people of Dunedin rejoiced…for one month. In December a storm – which the Esplanade designers hastily assured the press was an “unprecedented event” – damaged the access ramp.

Then in June of 2013 large swells saw gaping holes open up in the pavings of the Esplanade as it was once again undermined, and of course by then the stairs and ramp had both failed several times in what the Council now conceded stemmed from design and construction issues.

In 2017 and 2018 debate again appeared in the Otago Daily Times about whether a new groyne, built over the existing piles, might help or hinder the state of the beach.

Which brings us up to the time of writing – no longer the shining summer of my visit. It’s winter in Dunedin and storms are once again stealing the sands of our seaside resort. Local Facebook groups are a-flutter with concerns for our dwindling beach and demands that something be done about it.

So what’s it to be? Will we finally try out that breakwater? Redesign the Esplanade yet again? Or shall we build new groynes just as the last remnants of the old slip away into the sea after a century of standing sentinel over the shifting sands?

Whatever our next move in this one-sided battle with Nature, I expect we’ll be re-hashing the options again in another twenty years. Meanwhile, Nature – unaware she is even engaged in a war – will continue to do as she always does: scour away the sand in winter storms and bring it back on spring tides, carelessly sweeping away all obstacles in her path.

References:

The Otago Daily Times. WEDNESDAY, MARCH 28, 1884. Otago Daily Times, Issue 6898, 26 March 1884

INROADS OF THE SEA. Wanganui Herald, Volume XXXII, Issue 9479, 4 July 1898

THE OCEAN BEACH SCHEMES. Evening Star, Issue 10792, 29 November 1898

OCEAN BEACH DOMAIN BOARD. Otago Daily Times, Issue 11191, 13 August 1898

OCEAN BEACH CONSERVATION. Evening Star, Issue 11726, 9 December 1901

Untitled Poverty Bay Herald, Volume XXX, Issue 9866, 7 October 1903

TOWN EDITION Poverty Bay Herald, Volume XXXII, Issue 10377, 7 June 1905

THE RIDDLE OF THE SANDS Otago Daily Times, Issue 17915, 21 April 1920

ST. CLAIR GROYNES. Evening Star, Issue 17536, 16 December 1920

Groynes buffeted by failure, opposition By Craig Borley

Evening Star, Issue 17594, 24 February 1921

ST. CLAIR GROYNES. Evening Star, Issue 17597, 28 February 1921

ST. CLAIR BEACH Evening Star, Issue 17649, 30 April 1921

DOMAIN BOARD Evening Star, Issue 18300, 13 June 1923

St. Clair, Dunedin : newspaper clippings by Dunedin Public Libraries.

Our St Clair : a resident’s history by Barbara A. Newton

St Clair Esplanade opens up by Rebecca Fox

New groyne could offer ‘buffer zone of protection’ by Jono Edwards

Groyne may cause more erosion, expert says by Jono Edwards

Still pursuing St Clair groyne plan by Jono Edwards

A wonderful tale of nature’s cyclical events with a few jabs of human nature thrown in .

Is there a coast guard who is always on guard?