When I last left my ancestors the Parsons, they had just stepped off the Timandra and into their new lives in New Plymouth. That was in 1842, but now I’m going to skip ahead eighteen years to the outbreak of the First Taranaki War – perhaps the greatest challenge they had faced since fleeing the hungry forties in south-west England.

That’s not to say the intervening time was unremarkable, just that it was characterised by intimate family events rather than the sort of stuff that could change our country’s history. Thomas, an infant during the voyage from Old Plymouth, had grown to manhood. He had been joined in this new country by siblings Mary Sarah, William, Elizabeth Jane and Fanny. His father John had for some years been unsuccessfully trying to sell the family farm, which today is long gone but not entirely wiped off the map.

The Parsons had put their trust in the New Zealand Company when giving up everything to settle here, but we’ve already covered some of their many failings, including their tendency to be a little too casual about ensuring their land purchases were legitimate or even that the land they were selling actually existed. By the late 1850s these problems had become the New Zealand Government’s problems.

The New Plymouth settlement was especially hurting for land. But with the balances shifting (Pakeha outnumbered Māori for the first time in 1858) North Island Māori were becoming more and more reluctant to sell their land. Complicating matters, Māori disagreed among themselves, and even when somebody could be found willing to sell, their right to do so could be disputed by others who also claimed mana over the land.

It was only a matter of time before these tensions erupted into conflict, and the spark that lit the fire was a land purchase at Waitara, which the government decided to proceed with despite objection from Wiremu Kīngi, the rangatira who claimed mana over said land. In the words of governor Gore Browne:

The question of the purchase of an insignificant piece of land is merged in the far greater one of nationality.

Governor Gore Browne

At the time there were two types of settler-soldier, the Volunteers and the Militia. The Volunteers were just what the name implies – men who volunteered their service to (in their view) protect their homes. The Militia, on the other hand, could be called up by conscription if the situation seemed dire enough.

On 22 February 1860 it was decided that the time had come, and two members of the Parsons family were called to serve – the patriarch John Parsons and his eldest son Thomas.

I must wonder about their feelings at this. They did not volunteer; they were legally required to take up arms. Did they do so reluctantly? New Plymouth was the only home Thomas had ever known – how did he feel now that it was under threat? John had given up everything to move his family here, to find the land he’d purchased sight unseen now rendered worthless thanks to the “unsettled and perilous” condition of the province.

I wonder if he was simply fed up with it all. He was trying to sell – he wanted out. But now at the age of 46 he was ordered to take up arms to defend the worthless tract of land he couldn’t even sell.

There is, of course, a dangerous temptation to absolve my ancestors from the guilt of their part in an unjust war, by filling in the gaps in the evidence with my own wishful-thinking story of reluctant conscripts.

Of course I can never really know, for the record contains only the fact that they served, and does not tell what lay in their hearts. And this story doesn’t involve John. This is about what his son Thomas experienced at Waireka.

The first battle of the First Taranaki War occurred north of New Plymouth with an assault upon Wiremu Kīngi’s famous “L-Pa”. Meanwhile supporters gathered to the south, various hapū of Taranaki and Ngāti Ruanui, who built a temporary pā called Kaipopo on Waireka Hill (also known as Jury’s Hill) overlooking the coastline and the road south, even commanding line of sight to the beleaguered settlement.

Of course, I was determined to visit the site of Kaipopo, the fort that my forbear faced – willingly or not. It’s private farmland now, and no trace of the makeshift palisade or hastily-dug rifle pits remains, having been wiped out by later use. But at the corner of Waireka Road West and Sutton Road there is a single humble reminder of the struggle.

As outlying settlers crowded into the town for safety, they were startled by news of the killing of five settlers by the Māori entrenched to the south. Worse, there were five households in the area who had not yet made it to the safety of New Plymouth.

There was nothing for it but to devise a rescue. The plan seemed simple on paper: a force composed of about 50 Militia (Thomas among them) and 100 Volunteers would approach via the beach and swing around behind the pa to where the imperiled settlers were sheltered, while a separate contingent of about 120 soldiers of the 65th Regiment (professional soldiers imported from England) under the command of Liuetenant Colonel G. F. Murray would march down the Main South Road to secure the route back into town. There was also a small contingent of naval “blue jackets” from the visiting HMS Niger in company with the 65th.The Volunteers and Militia were to swoop in, secure the families and meet up with the professionals, then together they would all return to New Plymouth. All to be completed before dark – as per the orders of Colonel Charles Emilius Gold, the man in charge of the military action in New Plymouth.

These two forces marched on 28 March 1860. Captain Murray led his troop south to Omata stockade, which at this time was not yet complete, although some men were already posted there. Not meeting any opposition he ventured a little further, then settled down to wait for the colonists to do their part.

Meanwhile the Militia and Volunteers were making their way along the beach. Inexperienced and barely trained, some among them were all to eager to engage the enemy.

Watching from Kaipopo, the defenders were in prime position to follow all these proceedings. It may have been naive to think that they would sit tight and let the Europeans run rings around them, and in any case they did not, and made their way down the hill through the Waireka gullies that ran to the beach.

The fight was on.

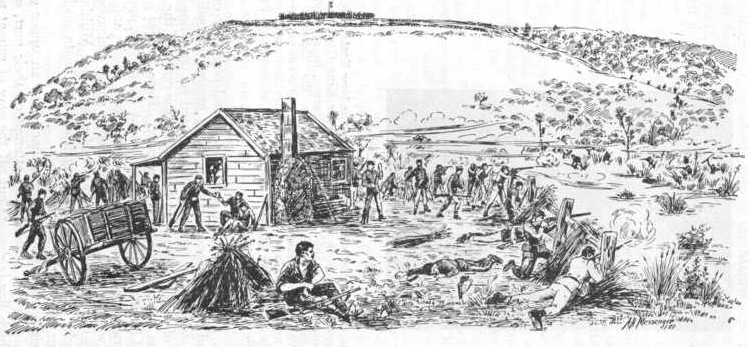

A party of Volunteers reached an empty farmhouse on the flank of the hill, which they were able to convert into a passable defensive position. The Militia, presumably including Thomas, climbed a steep hill positioned between the two main gullies so as to cover them.

Captain Murray, hearing the gunfire, sent what little help he could while focusing on his main objective of keeping the road open. But at about 5.30pm, mindful of his order to return to New Plymouth before dark, he ordered his troops to retire.

Meanwhile, the settlers were in a precarious position. The Militia managed to cross over to join the rest of the force at the farmhouse, and there they hunkered down to face the night. They were almost out of ammo, unable to retreat the way they had come thanks to the rising tide, and fearful that one good rush from the Māori might be the end of them.

One later recorded in his journal:

As we lay inside our fort waiting for the young moon to go down, not knowing what execution we had made, & only guessing what had happened on the hill, we had almost given up hope. Very few of us expected to see town again, for besides our want of ammunition and our wounded we had a long flax gully to go through where they might easily have made short work of us. I remember looking up at Orion just visible between the clouds & wondering whether I should soon be up among the “unvoyagable stars”…

Arthur Atkinson

He was not to join the stars that night, however.

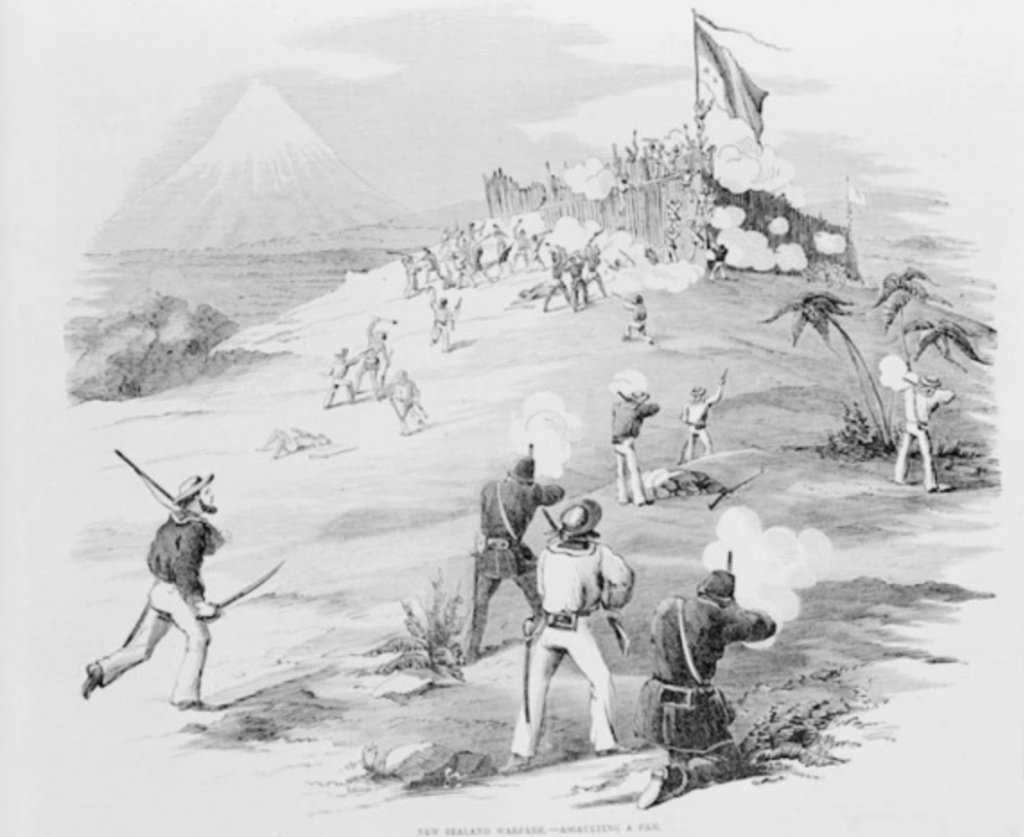

On to the scene swept the saviours of the hour: Captain Peter Cracroft and his sailors off the HMS Niger, a British Royal Navy ship which had been assigned to the New Zealand coast in anticipation of the brewing trouble. These “blue jackets” stormed the pā and successfully its flags, but seeing that Murray had returned to New Plymouth they gave up the position and followed.

Though they may not even have known of the situation down in the gullies, their decisive action proved just the distraction that was needed. The stranded militia waited until the dark of night before effecting their retreat. Unable to return along the beach, as the tide had risen, they were forced to make their way through the bush, an arduous journey even for the able-bodied. It was midnight before they made the safety of the town.

Perhaps you might be wondering about those five settler families, the ones for whom this entire exercise had been launched to rescue? They arrived in New Plymouth the day after the operation, entirely unharmed. In fact they had probably never been in any danger at all, as they had been given the protection of tapu and told that they would not be harmed if they did not move from the place they had taken shelter.

In the aftermath Captain Cracroft and the blue-jackets were hailed as heroes, while Colonel Gold and Lieutenant Colonel Murray were heavily criticised for their decisions, especially the choice to retreat and leave the settler-soldiers to fend for themselves. As time has gone on, tales have been spun, legends have grown and in turn been challenged by more recent historians. There have been numerous questions raised about the happenings at Waireka, chief among them whether the outcome could truly be called a “British victory”, or if it should be relegated to the ranks of “paper victories” (in other words, only recorded as a victory thanks to who held the pen).

The answer is not a simple one, and perhaps lies in how you might define a “victory”. In the traditional British sense, taking the enemy’s position – and its flag – is a sure-fire sign of victory. Māori approached war rather differently, often holding a position only as long as it remained practical before quietly abandoning their fortification to regroup elsewhere. Perhaps we can count it as a tactical win in that the Māori forces gathering to the south did disperse, which might indicate the show of force had given them second thoughts.

On the other hand, if you consider a victory to involve achieving one’s stated goals, then this was a miserable failure for the British. The poor families at the centre of this were all but forgotten as the militia got bogged down, the soldiers went home, and the Navy conquered the hill. Had they truly been in danger, nothing the British did would have saved them.

We might also assume the Māori failed to achieve their goals, although their intentions are more difficult to determine, thanks to the lack of written records on their side and the general tendency for history to be written from the British perspective. If the intention was to hold the hill, they failed, but as I said earlier, “holding” a position is a very European way to measure the results of warfare.

If you would rather approach the question as a numbers game, you’ll run into another problem. While the British casualties are well documented (two killed and 14 wounded), estimates of Māori losses vary wildly. British reports suggest 46 or more were killed an an unspecified number wounded, but only about 17 can be confirmed with any certainty.

Personally I don’t feel like anybody “won” here, but I’ll leave you to draw your own conclusions.

As for Thomas, he was awarded the New Zealand Medal for his service in the battle of Waireka, and from there seems to fade from history. If he served in any other battles, I haven’t found any record of it.

It appears he never married or had children of his own, and he died in 1906 at the age of 68. As he passed without heirs, the medal is now held in the Puke Ariki collection.

I guess that’s the way it goes for most of us. Though we might live through perilous times, our impact is small and easily overlooked. Perhaps in a hundred years time, if someone remembers me, it might only be because we share a tenuous tie of blood, or through some relic in a museum collection.

I don’t think that means that life isn’t meaningful, or not worth remembering. I think there’s something special about remembering those who might otherwise be forgotten.

References:

The Battle of Waireka 28 March 1860 An anthology of eyewitness accounts by Graeme Kenyon

OBITUARY. Otago Daily Times, Issue 13716, 9 November 1906, Page 4 (Supplement)

Images:

Artist unknown :New Zealand warfare – attacking a pah [Storming the Waireka Pah, Taranaki … 1863]. New Zealand. Internal Affairs Department :Making New Zealand; pictorial surveys of a century. Wellington, Department of Internal Affairs, 1940.. Ref: PUBL-0098-02-24-06-lower. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/23074257

One thought on “What Happened at Waireka”