Endangered church buildings seem to have become all too common of late. Two years ago I rushed to the Hillside Wesleyan Church mere days before it was torn down to be replaced by a car sales yard. But now it seems every other week that another Dunedin church is either in danger of being demolished or sold into private hands.

Highgate Church, and its uncertain fate, stood out among these stories as being somewhat more contentious than usual. A significant community opposition movement had formed, and so I set out to investigate this thorny issue, find out why we are losing our churches, and who our built heritage really belongs to.

The building first came to my notice back in April upon seeing the ODT’s attention-grabbing headline: Church ‘covering up’ building’s true state. This was followed four days later by an equally sensational sequel: Church threatens legal action against demolition opponents.

Conspiracy! Controversy! Given this backdrop there was no way I was missing the public meeting organised by the group opposing demolition, attended (by my count) by almost 50 people, and to be held in the Coronation Hall just across the road from the church in question.

We were greeted by Richard Macknight, one of two brothers spearheading the church protection movement, and our chairperson for the night. At the heart of his argument was one factor I’d not considered in my previous look at the topic. He acknowledged that the community legally has no say in what the church does with its property, but because the community itself invested in the building of the church a hundred years ago, they should now be given due consideration when deciding its fate.

So let’s take a look at how this all began. Before 1905 the Presbyterian devotees of this area were served by Knox Church, in which parish they were located. By 1904 the idea was being floated of Sunday School and evening services being held “up the hill”, and so a committee was sent out to canvass the households in the district to gauge support for the idea.

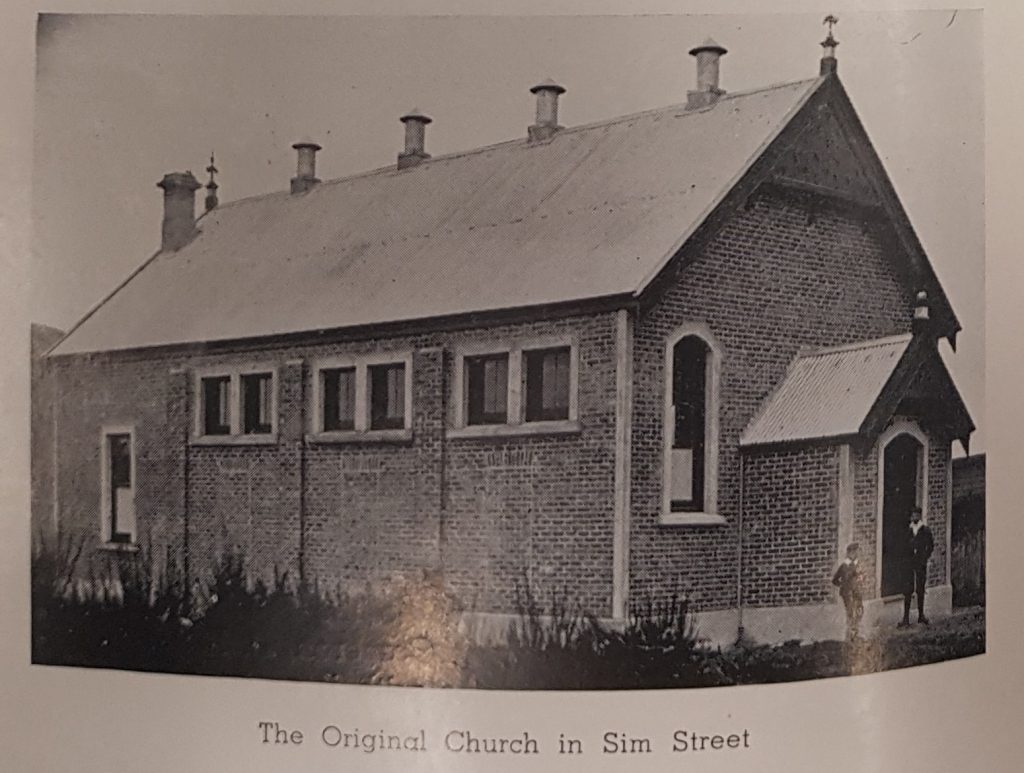

The numbers came in: 58 families were keen, consisting of 188 members, of whom 64 were children. The first church building was located in Sim Street and opened on 26 March 1905. Indeed the community did contribute toward the work, with the “ladies of the district” holding a sale in April of that same year in an effort to clear the debt for the work.

In 1907 Maori Hill was made a “sanctioned charge” which meant they could call their own minister instead of sharing with Knox Church. It was the second minister, Reverend H. H. Barton, whose tenure saw the construction of the present building, after the congregation was forced to use Coronation Hall, having outgrown the Sim Street premises.

The new site was duly purchased in 1917, but events intervened before construction could begin, and the existing building was hastily converted into accommodation for children whose parents had died or been “laid aside” by influenza. The 1918 flu epidemic swept through the country, killing as many again as had just been lost in the First World War, but in a matter of months rather than years.

The foundation stone was finally laid on 18 September 1920, and the community interest was represented by two of the guests of honour for the ceremony – the mayor of Maori Hill (back when that was a thing) and his “mayoress”.

The building was opened on 9 March 1922, to a total cost (including furnishing, fencing and heating) of £12,859 19s 8d. That’s about $1,258,545 in today’s dollars, and a debt of about £5000 remained even after all efforts to fund raise, which – thanks to the great depression lurking just over the horizon – would take seventeen years of hard work and special appeals to fully clear.

Back to the present, and we heard from Richard’s brother Steve, an experienced heritage developer. He contended that the work required to get the building up to earthquake safety standards is likely not nearly as prohibitive as its owners claim. “Earthquake safety” has been the death knell of many a historic church, but in this case is it simply the scapegoat?

Steve spoke of the fact that this is one of the only historic landmarks in the area, of how it provided a connection to the past and represented the sort of community ties that we once had but seem to have lost in this modern age, of how this building could perhaps form a hub to rebuild those ties.

And indeed in the mid-1950s, when the church was celebrating half a century, the congregation was “flourishing” with a membership of 397 and a focus on youth services. In 1965 the church boasted a Bible class roll of 100 and 248 children enrolled in Sunday School.

I was deep in contemplation of mid-century nostalgia when our third speaker took the floor, Andrea Farminer of the Dunedin City Council. Andrea harks from the UK and is therefore no stranger to this problem of ancient buildings, and had many suggestions for creative uses of the space such as subdividing into separate café and worship spaces where economic and spiritual needs could both be met. I couldn’t help but respect her opinion after my own observation of English churches that had been built before the first human had even set foot in New Zealand. If they can make those work, why can’t we?

After Andrea was Anne Barsby of the Southern Heritage Trust. Anne spoke of Dunedin’s unique history and cityscape, of the problem of shrinking and ageing congregations without the funding or bums-on-seats required to maintain old and elaborate buildings.

And indeed the church’s centenary in 2005 was quite different in tone from the celebration 50 years earlier. While the quinquagenary was characterised by an atmosphere of growth and hope, the sermon by Reverend Martin Stewart on the occasion of the centenary spoke of “the wilderness” encountered by Moses and the Israelites as they wandered in search of a place to call home. The Reverend likened this wilderness to the challenges facing the church in the current day, with its dwindling congregation, difficulties attracting new members, and a community seemingly no longer interested in religious matters.

Though the church had not sent any official representative to this meeting, a few members of the congregation still attended in an unofficial capacity. Two such people spoke next, the first pleading for understanding and trust in the Parish Council, who have gone through a long process to come to this decision and must have some very compelling reasons to do something so drastic as relinquish this fine old building.

The second took a far stronger position. Tony Borick is a congregation member of 50 years and both appalled at and completely opposed to the decision.

As I already mentioned, the church did not have any official representative at the meeting, so I’ve had to fall back on one of the earlier articles about the situation in order to get a sense of their point of view. The Reverend Geoffrey Skilton told the ODT that the building was no longer fit for purpose and had become too costly to maintain, and added:

I find it hard when people say the church should do this, and the church should do that. Where have folks been for the last 20 or 30 years?

It seems a fair point – it’s not really fair to obligate an organisation you don’t support to expend their own resources on causes that don’t advance their mission, just to soothe our own feelings about the past slipping away. If this is really about the community, then surely the community must pull its share of the weight, and not place it entirely on the shoulders of a church doing its best to adapt and survive in today’s changing religious landscape.

As the months went by updates on the embattled church’s fate continued to trickle out. The church agreed to put a hold on demolition plans so that the DCC could investigate alternative options, including availability of funding. A comprehensive report seemed to suggest that it was not earthquake-prone as defined by law, and may require less than $10,000 to bring it up to code. Tony lodged an appeal with the Southern Presbytery over the matter. Local residents gathered 800 signatures on a petition to save the building.

November rolled around and with it the Southern Presbytery hearing for Tony’s appeal. By now the petition had reached 1414 signatures. The decision came back favourably for both parties, keeping demolition on hold until further information had been gathered, but also absolving the Parish Council of any bad-faith action or misinformation around the matter.

Since then things have been quiet, and as we enter a new year the fate of the building still hangs in the balance.

I wonder why, with so many church buildings currently under threat, that it is this one in particular that has become our battleground. Perhaps it was the scandalous cover-up/legal-action angle that got us all invested, even though after that rocky start everyone involved seems to have calmed down and proceeded quite reasonably.

Or just maybe this this is about more than just one building, and Highgate Church is a stand-in for the nostalgia we feel for the connected and close-knit communities we once had. Religion may not be as central to our lives as it once was, but that doesn’t mean we want to lose our last tangible symbols of what that stood for.

It doesn’t mean we’re ready to give up on the idea of that community.

References:

Church ‘covering up’ building’s true state by Tim Miller

Church threatens legal action against demolition opponents by Tim Miller

“Spring up, O well!” : the jubilee record of the Maori Hill Presbyterian Church, 1905-1955 by Henry H. Barton

MAORI HILL PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH Evening Star, Issue 12478, 13 April 1905

NEW MAORI HILL CHURCH Otago Daily Times, Issue 18045, 20 September 1920

Maori Hill Church centennial service, 11th September 2005 : “Spring up O well”

Rethink call for churches by David Loughrey

Much effort made for eleventh-hour reprieve by Tim Miller

Report may save church by Tim Miller

Less than $10,000 to strengthen church, engineer says by Tim Miller

Support for Maori Hill church petition by Brenda Harwood

Church proponents eager to be heard by David Loughrey

Hope remains for Highgate church by Brenda Harwood

Confidence church can be saved by John Lewis

One thought on “Fight for Highgate Church”