Another ANZAC Day provided the setting for a now-traditional adventure between Dad and I. Dad suggested a road trip to Waipapa Point, where we could walk New Zealand’s southernmost beach. Seeing that the reef here was the site of the historic wreck of the SS Tararua, I agreed even before examining the locality more carefully by way of topo map, where I discovered the dunes at the eastern reaches of the beach were home to something marked only as “derelict gold dredge”. Serious adventure was afoot!

You know, it’s tough for me to travel through the Catlins. Every bend in the road seems to signal a point of interest, either scenic or historic. But we made it through the gauntlet of diversions to the remote Waipapa Lighthouse Road. Emerging from the controlled conditions of the vehicle into the winds of the remote southern beach, we caught our first glimpse of the lighthouse.

But distractions threatened even here, as our short route to the lighthouse was intercepted by a detour to the homestead site of the former light keepers, indicated by a cluster of severely hunchbacked macrocarpa trees.

All of a sudden I decided that today’s little bluster perhaps wasn’t all that bad. The keepers were encouraged to marry, so whole families were raised in this bleak environment from 1884 onwards.

Finally we approached the whitewashed lighthouse with its cheerful red door. The picturesque building belies the grim disaster that birthed it into existence – the wreck of the SS Tararua, which still ranks eighth in New Zealand’s top ten list of deadly disasters.

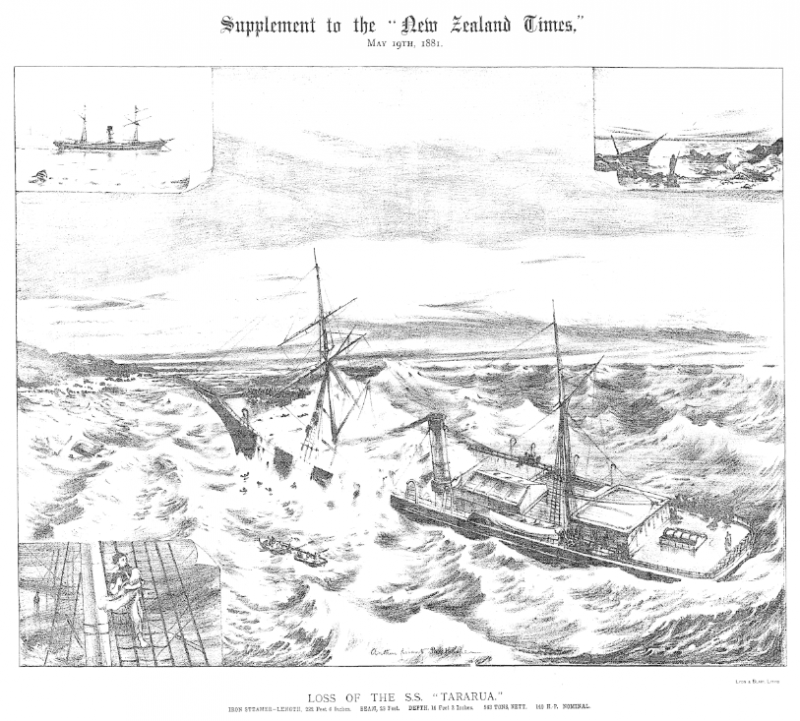

The Tararua, measuring 68m in length, was built in 1864 at Dundee by Gourlay Brothers and Company. Her first owner was the Panama, New Zealand and Australian Royal Mail Co but in 1869 she passed into the hands of McMeckan, Blackwood & Co, who gave her an overhaul and put her to work running mail, news and cargo between New Zealand and Australia. In that capacity she was fondly remembered as one of a fleet that was “indelibly connected with the rise and progress of New Zealand”, bringing across hordes of prospectors during the gold rush and promoting trade between the two fledgeling countries.

![The SS Tararua mored on the Roper River. Source: State Libraray of South Australia [B 4643]](http://adventure.nunn.nz/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2019/06/tararua-1024x778.jpeg)

She left Port Chalmers at 5pm on April 28, 1881, headed for Melbourne via Bluff and Hobart. She was under the command of Captain Francis George Garrard – though popular with passengers and known to be meticulously careful, he had been involved in more than one accident in the past. He was a member of crew aboard the Taupo when she struck a rock entering Tauranga Harbour in 1879, resulting in the loss of the ship, and and only two months earlier he had been asleep below deck when his ship the Albion had collided with the Isabella Pratt.

Prior to embarking on the voyage, a number of the Captain’s friends had gathered in his cabin to celebrate his upcoming marriage to a Miss Buckhurst, the daughter of a wealthy merchant residing in Emerald Hill, Melbourne. He was to be married upon his arrival in Australia, and planned to retire from the sea and join his new father-in-law in business.

With that kind of foreshadowing, small wonder the voyage ended in disaster.

The Tararua made it farther than the Victory, rounding Cape Saunders at 6.40pm. She continued southward in the darkness until 4am when she was turned to the west, the Captain judging that she had passed Slope Point. Soon after the sound of surf was heard, so the ship was nudged back into a more southerly course for twenty minutes before turning west again

Shortly after 5am she hit the rocky reef that extends out to sea just east of the lighthouse, about 1.2km from shore.

For the people aboard, that 1.2km over roiling sea to the safety of land might as well have been as wide and deep as Cook Strait. Damage prevented the ship from being reversed off the reef, and the engineer’s leg was broken in the attempt. Enormous waves swept across the deck and within ten minutes the foundering steamer had filled with water.

The first boat to be lowered was destroyed in the process of getting it in the water, although all occupants made it back on board.

The next, containing four sailors and passenger George Lawrence, was successfully sent out to find a suitable landing place. When halfway to the shore George bravely dived from the boat and managed against all odds to make the beach. He lost no time in running to the nearest house to alert the residents of the Tararua’s predicament.

He then returned to the shore in time to assist three of the six strong swimmers who had been ferried to the surf line in the second mate’s boat and then attempted to swim the gap. The other three did not make it.

The second mate’s boat then returned to pick up more passengers (including David Hill, who left behind his wife and child) and James Maher, a stoker, who swam to the reef in an attempt to find a suitable landing place there. While James was on the reef, three of the passengers attempted to swim ashore but were lost. James swam back to the boat, which was now unable to return to the Tararua as waves crashed over her and the women and children huddled terrified in the smoke room. Instead the small boat struck out to sea in the hopes of locating another vessel to bring help.

Another boat under command of the chief officer attempted to get a line ashore but was capsized, though eight of the nine occupants managed to make the shore. The last, a young boy employed to clean lamps, drowned.

By 2pm on the day of the accident the ship was breaking up. The women and children were shepherded on to the forecastle-head, many being swept overboard in the process. The last reported sighting of unlucky Captain Garrard was with this crowd in his charge, and the last words heard from him were “Oh God, what shall we do now?!”

Of those washed overboard, one person, chief cook John Wilson, managed to make it to shore.

As the day wore on the remaining passengers were driven up into the rigging in a desperate attempt to escape the sea, while those on shore could only watch on in helpless horror. As night rolled in, the occasional flickering light could be seen from the ship, as from a match being struck. At one point cheers could be heard, perhaps after sighting the light of the passing Kakanui, which they may have believed heralded rescue.

Then at 2.45am on 30 April the inevitable happened. Screams and shouts were heard, and observers claimed they could hear the captain calling for a boat to be sent, and then only the sound of the waves. When dawn came, the Tararua was almost gone from sight, and bodies were washing up on the sand.

Meanwhile, a horse had been despatched from the homestead George Lawrence had reached, carrying news of the wreck 56km to the nearest town, Wyndham. The telegram requesting help was despatched at 12 noon and, misleading despite being true to George’s knowledge at the time, stated that all passengers were safe. Even so, the Union Steam Ship Company had made the Hawea ready by 5pm that day and she approached the scene of the wreck by 6.30am the next day. Alas she was too late, and she could only pick her way through the wreckage and pick up the second mate’s boat from the care of the Prince Rupert, another steamer which had come upon the site of the wreck.

The Hawea lowered her boats to search for mail and bodies. The corpse of an infant was recovered and David Hill, one of the survivors from the second mate’s boat, was dismayed to discover it was his own child. In the days afterwards bodies continued to wash up on shore, and as it soon became impossible to identify them, 55 (or 64 according to another source) were buried in nearby Tararua Acre, which was where we now headed.

The tiny cemetery lies at the far end of a large field, just beyond the dunes. There are two memorials here, the smaller – a marble headstone – erected in 1884 with money raised by the children of Fortrose School. The other was put up by the community in 1960 in association with the Historic Places Trust.

The only remaining individual headstone is that of Auckland book-keeper William Bell, who was travelling to England in order to obtain medical treatment for a troublesome old injury to his leg. Instead, he ended up here.

The remnants of the steamer were sold as-is where-is for £20, though the £4000 of silver was rumoured to have been on board was never recovered. Could the silver be out at sea still?

Though other ships had been wrecked on this same point, this was the one that resulted in a light being placed at Waipapa Point. Had one been erected after any of the earlier wrecks this whole disaster would have been averted and 151 lives saved.

Sadly human nature always seems to demand a tragedy first.

References:

List of disasters in New Zealand by death toll

LATEST TELEGRAMS Wanganui Herald, Issue 505, 14 January 1869

SALE OF THE ALBION. Auckland Star, Volume XVIII, Issue 120, 23 May 1887

McMeckan, James (1809–1890) by G. R. Henning

The Observer 7 May 1881, pages 360-361

New Zealand Shipwrecks 1795-1960 by C.W.N Ingram and P.O. Wheatley

WRECK OF THE S.S. TARARUA. Evening Star, Issue 5660, 30 April 1881

WRECK of the UNION CO.’S S.S. TARARUA. Bay of Plenty Times, Volume X, Issue 1041, 17 May 1881

S. S. TARARUA.Ne w Zealand Times, Volume XXXVI, Issue 6272, 19 May 1881

Untitled. Observer, Volume 2, Issue 34, 7 May 1881

“TARARUA ACRE” MEMORIAL. Daily Telegraph, Issue 4031, 23 June 1884

SS Tararua Wreck Site, Tararua Acre, and Waipapa Lighthouse Site

The wife of my 4th great-uncle, Benjamin Paddon, was one of the heroes of the wreck. Susan (formerly Theresa Susannah Edge) and Benjamin were the storekeepers at Fortrose, and some of the first on the beach.

From ‘The Wreck of the Tararua, Joan McIntosh, Reed, 1970, p. 31: “… It was a heart-rending situation for those ashore, for now they saw wave after wave carrying people overboard, and though they searched diligently, they could not recover a single survivor. Susan Paddon became so distressed at the plight of the women and children that she urged her horse into the breakers as if to get nearer to help them. She did this several times.

P. 63: “…Public recognition was sought for several persons who had never been thanked or recognised for their services in connection with the terrible disaster. Among these were Mrs Paddon and her sister [Esther Octavia Boyer, nee Edge; incidentally her husband John Boyer is also a 4x great-uncle on the other side of the family!], who had worked nobly. Mrs Paddon stayed on the beach all night on one occasion and had washed some of the dead and prepared them for burial. She had done work which few women would have the courage or strength to go through with.”

The ODT in May, 1881, recorded a presentation made to Susan in regards to her work for Tatarua victims.

Susan died eight years later of ‘pulmonary phthisis” – tuberculosis.

Thank you for this great piece of family history. Poor Susan, it must have been such an upsetting experience for her!

I have visited the lighthouse on several occasions and have a framed photograph of the lighthouse I took about 5 or 6 years ago I also have books on nz shipwrecks but I was totally unaware of the monuments, how very sad but all to common in the 19th and early 20th century.Great to see the blogs coming again but family must come first.

Yes a very sad event but unfortunately many ships were wrecked on our coastline. Thanks for your comment and support!