As the sun rose on a sweltering 2019, I looked back on a year well spent. I’ve visited so many wonderful and far-flung places – the bustle of Auckland, the steaming shores of Lake Rotorua, and the regenerating streets of Christchurch. I’ve made pilgrimage to Aoraki, to the place where Maori and European first met, and even to the very gates of Moria.

Now I was freed from the bonds of work for the holidays, but my ambitious adventuring plans were curtailed by an ill-timed vehicle breakdown. Could there possibly be any adventuring potential within foot reach of my humble home?

As it turns out, my very own neighbourhood is as rich in history as any other part of New Zealand. So I stepped out my front door into the summer sun and began my journey into Caversham’s surprisingly rich history.

I headed straight for the corner of Fitzroy and Thorn Streets, for on Fitzroy Street there are two heritage listed buildings. I’d always assumed that the one at this corner must be the green two storied thing, but in fact it is the understated yet undeniably fine house opposite.

Unfortunately all the heritage list has to say about it is “house”. Further complicating matters is that up until 1905 Fitzroy Street was known as Smith Street, and the area between David and Surrey Streets was the “township of Calderville”, a subdivision of land owned by Hugh Calder.

Further up the street, Faringdon Villa is at least more forthcoming in that at least its name and date of construction (1882) are easy to work out.

Faringdon Villa was built by Richard Grimmett, who was a bricklayer, stonemason, and – later in life – a building contractor. He arrived in Dunedin in 1873, with his wife Charlotte Rachel and seven children in tow. Two more children were born in Dunedin, though one did not survive.

Charlotte has been described as a “first wave feminist”. She ran the family finances, was a staunch member of the Salvation Army (in which women could take important leadership roles), and was an agitator for women’s suffrage and the temperance movement. None of that sounds too radical these days, but back then her actions were a bold invasion of the male worlds of pubs, politics and power. A formidable woman, she would stand outside local pubs like the Waterloo Hotel and collect donations from departing patrons using her tried and true technique of “The Look”.

I ambled along up to South Road, and turned to the right, sparing only a brief glance at the Baptist Church (built in 1907) and the magnificent memorial arch at the Caversham School gate as I made my way to the crossing. They are just as historic as everything else around here, but I have to ration out my attention if I want to keep any semblance of brevity today.

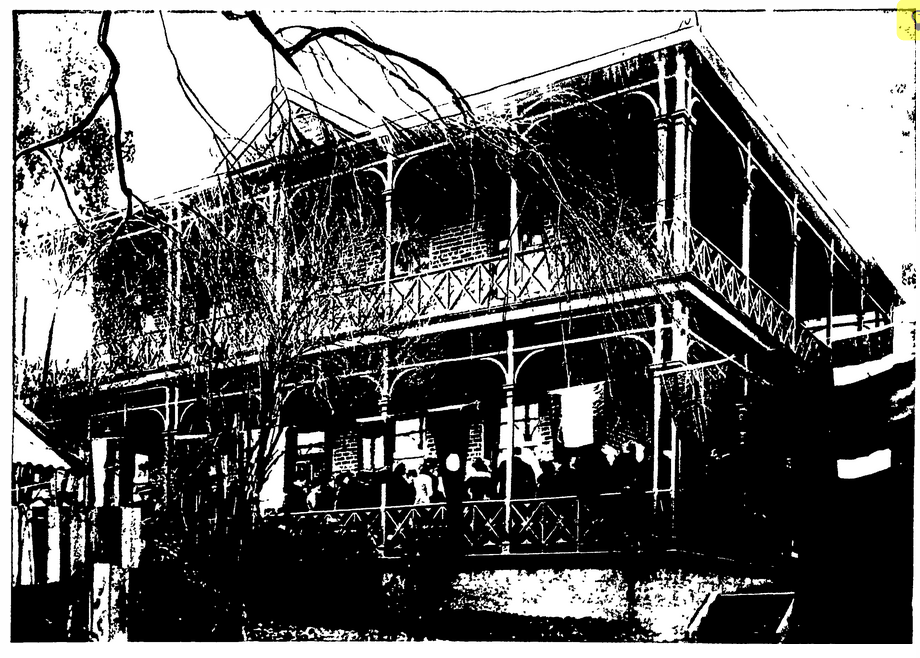

Now I headed up the short Lisburn Avenue to find one of Caversham’s most famous buildings: Lisburn House with its fancy brickwork and steep gables. This place was built by James Fulton, an arrival in 1849 by the ship Ajax, as a place for his family to stay when they visited town – their main homestead was located in West Taieri.

And yes, James Fulton was grandfather of that Fulton – Julius (Jules) Fulton, half of the partnership that became the Fulton Hogan civil construction company.

Once upon a time this house sat upon extensive grounds, but now the railway cuts through its back yard while urban sprawl crowds up around it.

I backed out of Lisburn Ave and headed up South Road toward the small shopping area. Sam McCracken’s old store is the most obvious relic here, although the business started out in the 1880s as a small wooden grain store soon after Sam and his wife Mary arrived from Ireland aboard the Dunedin in 1879. The two storied stone building was built in about 1900, and, along with rival grocer Peter Rutherford across the road, catered to much of the shopping needs of this young suburb in the days before “getting groceries” meant a jump in the car to Pak n Save (incidentally, the McCrackens were one of the first families in Caversham to acquire a car). Sam also apparently had a “primitive sawmill” in his yard, driven by an old horse who he occasionally encouraged by throwing chunks of wood at it.

Sam died suddenly on a trip home in 1930, and when Mary passed away five years later at the age of 85 she left four sons, three daughters and 21 grandchildren.

The family sold the business in 1949, but it continued trading under the McCracken name until 1977.

I turned up Goodall Street, past the peripatus painting, and crossed the bridge over the motorway, from which I was able to look back over the crowded houses of Caversham. Ahead of me one particular building stood out from the rest, a yellow brick structure dwarfing the surrounding homes.

Built in 1903 by the Salvation Army in what was then Catherine Street but is today McCracken Street, this building started life as a maternity home for “young girls who have been betrayed and ruined”. Here they were “helped over their trouble and, if possible, returned to their friends”.

In this work it supplemented the previously established “Rescue Home” for young women at Rockyside, which acquired its residents from brothels, police courts, directly off the streets, or in some cases when women turned up of their own accord or were brought in by friends.

In its first 11 months of operation, the 17-roomed home housed 37 young women. 25 babies were born here, and another 12 were taken in for nursing purposes. The average age of the women was 21, 11 were under 20, and four under sixteen.

Residents were expected to work at laundry, ironing, and sewing (with women’s and children’s undergarments a specialty). Musical evenings were also held, and of course the weekly march to church was a must.

One such resident was an unnamed woman whose son was committed to the Industrial School in 1904. She had arrived from Ireland a single woman only six months prior and at the time had a second child to support as well as the implied baby on the way. The judge decreed it “a class of immigration not very desirable for the country”.

In 1906 the maternity home was relocated to Heriot Row and the building is now a block of flats.

Turning to the left I approached another building I have long been convinced is a historic relic – the barn-like house on the corner of Barnes Drive and Sydney Street. When I learned that J. R. Briggs’ Standard Brewery once stood nearby I became convinced that must be the answer…until I discovered that this building had only been built in the 1990s. It seems the Standard Brewery is long gone, buried somewhere beneath the motorway or adjoining park, and whoever built this house this way must have done it on purpose.

I made a detour to the Caversham tunnel, today decorated with festive tinsel, but I won’t talk about that here since I’ve already covered it. Then I crossed back across the motorway at the lights and back on to South Road in a vaguely homeward direction.

Here I found another structure which has often intrigued me, the strange half-church next to a row of early tenement houses. This was the Caversham Methodist Church, relocated to this spot from Kew in 1915, replacing an older church at Forbury Corner. It was closed in 1978, with the congregation merging into the Wesleyan Church on Hillside Road. Ironically more of this building still stands than of the one that received the departing congregation.

I continued down the road, past a high green wall with barbed wire twisted around its decorative ironwork. I’ve been told that this used to be a Mongrel Mob pad, although it mustn’t be any more unless the Mob is in to classic cars, which is what I saw when I peeked through the open gate.

I stopped to pop in to the adjoining Bill’s Antiques, where I was delighted to find a plethora of local history books and the current owner of Faringdon Villa himself. Weighed down with new treasures, I continued on my way, turning back down David Street to my final stop.

This building was the home of the New Zealand Wax Vesta Company from 1901, though the company was founded in 1895 and operated out of the old Caversham Immigration Barracks before setting up shop here. It was known as “Rutherford’s”, the Rutherford in question being manager Robert W Rutherford, son of Robert Rutherford (who was also a shareholder), first mayor of Caversham and brother of Peter Rutherford, Sam McCracken’s rival in the grocery trade.

The Company manufactured matches by passing long lengths of cotton through a waxing machine, then through a drying machine and repeating until a thick enough coating had been achieved. Then they were cut and placed in the dipping machine. The match boxes were also made on site.

The majority of the employees here were unmarried women, daughters of unskilled labourers who suddenly found that the industrial revolution had given them new opportunities to work outside the home. Not everyone in the neighbourhood was impressed, calling the girls “matchy tarts” and complaining of their “yahooing” and carrying on in the streets on a Friday night – despite Mr Rutherford’s stern admonitions to keep things respectable.

Though the industrial revolution provided new opportunities, it also introduced new dangers. The white phosphorus that made the “strike-anywhere” matches so convenient was also deadly poisonous, and anyone who worked with it for extended periods of time was at risk of developing “phossy jaw”, a hideous disease that destroys the jaw bone and eventually enters the brain.

Thus far we’ve only found one Caversham victim, William Norman. It might seem odd that the only known victim is a man when the vast majority of the factory employees were women, but this can be put down to a couple of factors.

First off, women were usually employed for shorter periods, often leaving the job once they got married. Up until that time they could earn more than many boys their age, but once they were married they would receive a married woman’s rate as it was assumed that their husband would take on the bread-winning role.

Secondly, the 1894 New Zealand Factory Act forbade women and children from working in the mixing or dipping of phosphorous matches, meaning the women were more likely employed in the waxing and box-making departments and thus less directly exposed to the dangerous chemical. I’m not sure why it was still considered okay to expose men to the danger of such a grisly occupational disease, and it seems the government eventually agreed, outlawing the use of white phosphorus in the manufacture of matches by 1911.

I suppose, as with every new technology, the law takes a while to catch up with the reality.

William’s story is covered well in the link above, so I’ll leave you with only this quote from his wife Annie, who cared for him as the fatal disease progressed, eating away at his face. She spoke of the day her husband remarked:

“Oh…there’s something sticking out of me gum” And he pulled it out. It was a piece of bone, a small piece, just like the end of a chop, where it’s perforated.

Let’s all take a moment to finish screaming.

The match factory operated here until 1953 and the building went through several other hands, including that of a woollen manufacturing company and as the premises of H.E. Shacklock, Dunedin’s own coal range and electric oven manufacturers.

And with that I ended my little neighbourhood tour. Turns out that if you live in a place like Caversham, a car is not necessary if you want to find history. This little snapshot of early Dunedin has given me a glimpse into the lives of temperance campaigners, fallen girls, and life working in the first factories.

What history awaits you in your neighbourhood?

References:

Building the New Word: Work, Politics and Society in Caversham 1880s-1920s by Erik Olssen

The Edge of the Town: Historic Caversham as Seen Through its Streets and Buildings by Alma Rutherford

Christianity, Modernity and Culture: New Perspectives on New Zealand History edited by John Stenhouse, G. A. Wood

WEST TAIERI CEMETERY Dunedin Family History Group Newsletter Issue 46 Oct 2011

OBITUARY Otago Daily Times, Issue 23048, 26 November 1936

THE SALVATION ARMY. Evening Star, Issue 11916, 18 June 1903

SALVATION ARMY SOCIAL AND RESCUE WORK. Otago Daily Times, Issue 13010, 27 June 1904

SALVATION ARMY. Mount Ida Chronicle, Volume 29, Issue 1506, 9 September 1898

Page 5 Advertisements Column 2 Evening Star, Issue 12129, 25 February 1904

CITY POLICE COURT. Otago Daily Times, Issue 12931, 25 March 1904

The Salvation Army Maternity Home. Otago Witness, Issue 2728, 27 June 1906

PASSING OF THE WAX VESTA. New Zealand Herald, Volume XLVII, Issue 14441, 6 August 1910

Sites of Gender: Women, Men and Modernity in Southern Dunedin 1890-1939 edited by Barbara Brookes, Annabel Cooper and Robin Law

Wow this is amazing I used to live in Sydney street for seven years. I didn’t know the history especially the big yellow house on barns dr. Thanks Amanda

Smith Street was named after Hugh Calder’s wife Marion Young Smith. There was also Marion Street now named Thorn Street.

David Street was named after Hugh’s father David Calder.

Yes he named a lot of streets after family members! Some of them were changed in 1905 when Caversham merged with Dunedin, to avoid double ups. That’s also why Cargill Road was renamed Hillside Road

I was told the house I live in was Dr Morrisons surgery, could you confirm this or have any history on Dr Morrison?

There’s an Arthur Morrison who was an MHR who lived in Caversham but he doesn’t seem to have been a doctor. Without knowing more about where you live or when Dr Morrison would have been practising, I probably can’t help 🙁

Its a house up Morrison street, it has the old steps that lead to no were

This was very interesting as I e mentioned before my great grandfather had a connler shoo at for ur corner from memory I think behind shackloocks building would love to here anything if anyone knows anything about shops in that area from what I know around early 1900’s

Does anyone know about the old quarry by 27 Lindsay road in the forest below?

Because in the book (The edge of the town) 27 Lindsay road used to be home of John turnbull Thomson a chief surveyor.

In 1858 he made his home at ‘rockyside’, building a house with with a small obsevertory I’m not sure if it’s the same house that’s sits there today but it’s quite interesting but it never says anything about the old quarry maybe it was built after the book because it was written in 1978.

We lived a few houses up from 27 Lindsay Road and I remember it was owned by the Andersons. We always thought it was a half way house for homeless people. The older Andersons lived across the road from us and I am sure it was their grandchildren that lived at 27 Lindsay Road. They could have been boarders.

The yard was always full of old abandoned cars.

‘i use to own and live at no 25 lindsay road.. at that time 1988-1990 thee where no other houses around me.. they had all been pulled down for the new motorway… then when they canned it they sold the remaing houses off… the sections sat vacant for years.. on the lower side of 25, there where a set of stairs that was a public walkway to thru the bush there…

Great history lesson – lived in Playfair Street Caversham for first 20 years of my life. All the children played happily in the street and In those days it was a very busy little suburb. Mr Cunningham’s dairy served us the biggest icecreams, best fish and chip shop directly opposite. McCrackens store for fresh cheese, Rutherford’s for groceries, Mrs Grants little drapery store, Shum’s with the most amazing range of fruit and vegetables, and the news agent where we purchased our comics. What a wonderful childhood when we never had a care in the world. Thanks for the memories.

PS Match Factory now being demolished for housing units.

Hi,

I loved reading your history tour of Caversham. I have just finiwriting a history of Patrick John Bellett who lived and worked in Caversham and St Kilda from 1859 to 1903. The Bellows Company ink and starch factory was located in South Dunedin near the gas works. It’s also mentions a Rankeilon Street. I wonder if the factory is still there.

The Woolen Company was “The Bruce Woolen Company” based in Milton. The factory made and assembled woolen garments. There was a works garden at the rear of the factory, with Roses and an Ornamental pool with live goldfish. I can remember it as a small child. The woolen mill was responsible for the erection of the brick building adjacent to the park.

When was smith Street in Caversham changed to Fitsroy Street. My great grandparents built Farringdon Villa in what is now known as Fitsroy Street.

Hi Noel, a lot of the street name changes happened in 1905 when South Dunedin was merged with Dunedin City. All the street names that would have been duplicated were changed.

Just found this website, Richard Grimmett was my great great great (I think) great Grandfather and built Farringdon Villa.

There is also a book (no Gravestone in the Ocean) about the Voyage the Grimmetts undertook from Plymouth to Dunedin and I believe the Voyage ticket is still in tact at Otago Museum I believe but the ticket clerk wrote the name incorrectly as Grinnell – which is what they state in the book incorrectly too.

Farringdon was names after the town in (now Oxfordshire( Berkshire which Richard and Charlotte met and married in. I was at the house in whhich they lived prior to leaving for NZ just days ago, still gotta get to Dunedin to take a look one of these days.

It’s “Faringdon villa”, not farringdon villa