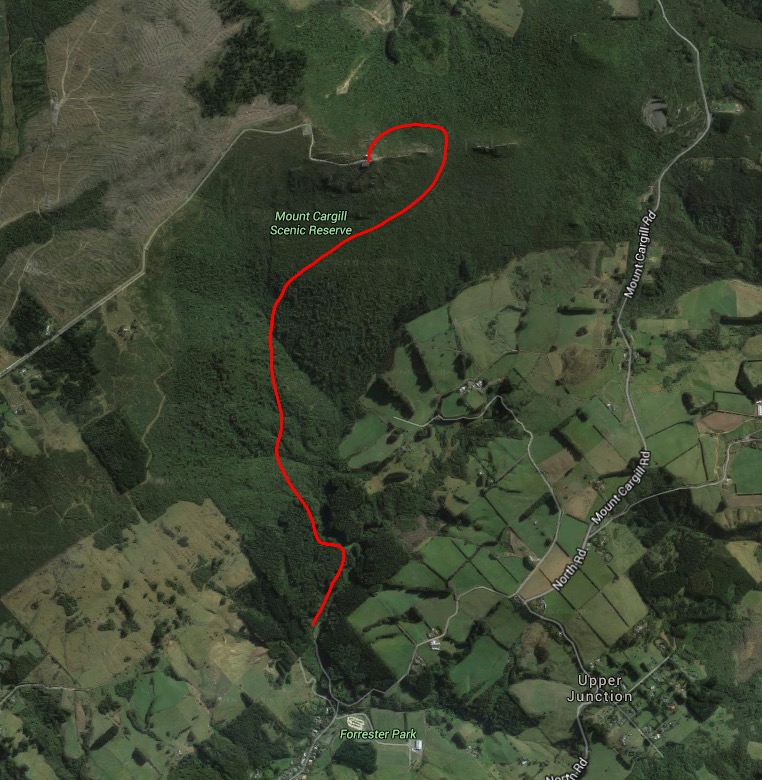

We’d already climbed Mount Cargill the easy way, so today we were back to do it the hard way. The route from Bethunes Gully in the far reaches of North East Valley to the Mount Cargill summit is roughly twice the length of the one from Mount Cargill Rd to the top, and it doesn’t take in the Organ Pipes. However, as we discovered, there is still a lot to interest a daring adventurer!

We passed through town and up North East Valley, taking a left on to Norwood St instead of following North Rd up the hill. Just past the bike and dog park we reached the gated entrance to Bethunes Gully.

We parked up by the picnic area, complete with barbecues and playground, and prepared for the great ascent. The morning was overcast but calm, perfect conditions to climb a mountain without overheating.

We parked up by the picnic area, complete with barbecues and playground, and prepared for the great ascent. The morning was overcast but calm, perfect conditions to climb a mountain without overheating.

We headed up the grassy clearing between Lindsay Creek on one hand and tall pines on the other. The famous Bethune of Bethunes Gully is David Bethune, a butcher who arrived in New Zealand aboard the Sevilla with his parents in 1859, and bought the land in 1878 (incidentally, I found a note that the correct pronunciation of the name should be “Beeton” but I don’t think I’ve ever heard anyone say it that way).

Bethune was the first to make radical improvements to this property, although there is little sign of most of them today. There was a house, kiln and slaughter yard near the gate of the property, and a sawmill and workers’ cottages elsewhere – it was said that many homes in North East Valley owed their existence to timber and bricks from Bethunes Gully. Where the picnic area is now, sale yards were built but never used.

He kept peacocks, geese, parakeets and pheasants, some of which occasionally got out of control. Today those were gone, replaced by a lone tui calling from the branches of a tree fuchsia at the edge of the field.

David Bethune led a pretty troubled life. A neighbour from before his time at the Gully claimed that he was a nuisance, that because of his “habits of life” they had to keep their children away from him, and that he had offered to fight any man for £10.

It seems David suffered from alcoholism, which his son tried unsuccessfully to mitigate, following his father to the pub on occasion and losing his temper at the bartender who served him. David suddenly wrapped up his affairs and left the gully in 1884. He went back to butchery after a few years but was “never the same”, and was staying at a boarding house when he was robbed while intoxicated in 1903. His son got a prohibition order on him but it was too late – David died soon after from a broken blood vessel in his stomach, which the doctor declared to be a result of excessive drinking. He was 66.

It was a strange and sad downfall for a man who had developed his property with such gusto, and had once been known and respected throughout North East Valley.

Further up the gully, we spotted some concrete structures by the creek.

I’m not sure if these are relics of David Bethune’s time or if they hark from the time of John Begg Thompson, who fell in love with the by-then overgrown property and purchased it in 1916. Thompson installed a water wheel to cut up firewood and with this being so near to the creek, it makes me wonder if it is somehow related. The waterwheel itself was washed away in the floods of April 1923. Some of the debris ended up in the harbour as far away as Macandrew Bay and other parts were looted by neighbours downstream as they floated by.

Thompson, irritated by constant trespassing and vandalism, offered the property to the DCC in 1930, and it has been here for our enjoyment ever since. The DCC apparently once also offered “boilers” for picnickers to sanitise water from the creek, so maybe the concrete “thing” could be a remnant of a fireplace used for that purpose.

We continued past the last grassy area and up into a stand of douglas firs. Coming up this way when I was younger I was always spooked out by this part of the journey, surrounded by bare trunks as far as I could see and hearing the creaks and clonks as the trees knocked together in the wind. No wind today though, so the plantation seemed almost friendly. I was surprised how quickly we passed it and emerged into the native bush that cloaks Mount Cargill. In my memories this stage was always much longer (and very dark for some reason?), perhaps because it was the part that made the biggest impression on me.

Whether it was the time or the season or just the normal state of affairs, we found ourselves surrounded by bird life. There were tui, bellbirds, fantails and kereru in abundance. A pair of tuis in a tree ahead of us were so engrossed in their conversation that they didn’t notice us until the last minute. Startled, they left to continue their discussion elsewhere.

We crossed a new-looking wooden bridge across a slip and another further up over a branch of Lindsay Creek, both giving us the opportunity to look out over the treetops back towards civilisation. Further up, there was a little detour to a picnic area and bench – the sign said five minutes, but it was more like 30 seconds. From here we could see across the gully to the summit, tantalisingly close although we would have to detour around the ridge to reach it. Below us kereru burst from the treetops before swooping away to a new perch.

We returned to the track, just as a kereru exploded through the trees above us and swooped over our heads, to the surprise of all parties involved. Its companion soon arrived and they proceeded to ignore us.

Nearby we found some large red-orange berries hanging from the dangling fronds of a miro tree. They are edible, so we gave it a go, sampling the thin layer of flesh that coats the big seed. I found it to have an acrid taste that lingered in my mouth for the rest of the walk. My guide book describes it as “barely edible” and tasting “strongly of turpentine” so I guess this is another native food to avoid unless truly desperate.

Traversing the ridge, the thick forest began to give way to more compact alpine plants. This always cheers me up, because it means I’m really getting somewhere.

Picking my way carefully along the rocky walkway, I admired the otherworldly alpine mosses and lichens that lined the edges of the track.

Then it was one last push and we were at the summit! From beneath the TV tower we surveyed the vista before us, which included the entire harbour from Aramoana to the city.

I tried to pick out all the spots I’ve visited in my past nine months of blogging – there’s Quarantine Island, Harbour Cone, Harington Point…and in the distance the one that got away: Mount Charles, the highest point on the peninsula, which I’ve been told is closed indefinitely to public access.

After resting and enjoying the view, there was nothing for it but to head back down. The trek had taken two and a half hours and we were regretting not bringing our lunch. But stiff legs and a late lunch is a small price to pay for the right to say we’ve conquered Dunedin’s most famous landmark from both sides!

References:

PRONUNCIATION OF SOME ENGLISH NAMES. Hawke’s Bay Herald, Volume XXI, Issue 6878, 6 June 1884, Page 4

Bethune’s Gully : how I obtained it and what I did with it by J.B. Thompson

Bethunes Gully a Popular Picnic Spot Otago Daily Times, 26 December 1958

RESIDENT MAGISTRATE’S COURT. Otago Daily Times , Issue 3566, 10 July 1873, Page 3

CITY POLICE COURT. Evening Star , Issue 10870, 2 March 1899, Page 2

A Field Guide to the Native Edible Plants of New Zealand by Andrew Crowe

Love the new design! Gorgeous photographs too. And, as always, excellent writing!

did the track take 2.5 hours each way?