Spring of 2021 saw some wild weather in the south, with storms and high winds featuring strongly on our radars. This curtailed our adventure options in the short term, but as always the post-storm calm brought new revelations.

One we found by chance at Aramoana, and a few weeks later we decided to return to document it properly.

Knowing what we were looking for, a clue at the car park took on more meaning. Was this part of the relic just lately uncovered? Tough to know, as the mysterious rusty bucket was presented without context.

We made our way toward the spit, dodging the profusion of man-o-war jellyfish that also seem to have turned up just lately (prompting one concerned citizen to ring the city council, before reporting back to Facebook that our elected officials were scandalously indifferent to the threat posed by the hazardous hydrozoans).

Lucky for us, we made it to the end of the spit without incident, rounding the rocky point to the narrow end opposite the Harington Point fortifications. Here our treasure awaited, newly exposed in all its rusty glory.

But whose buckets are these, and how did they get here? No, it’s not an abandoned mining jig like the one still lying in the Waipapa dunes. For the answer, we have to go back all the way to the first European use of Otago Harbour as a port, and pay a lot more mind to the movements of sand than I’d ever expected I would.

When the first Pakeha arrived in Otago, Dunedin harbour at low tide was a shallow mire of sand flats and winding channels. The harbour was only navigable for ships of up to 6m draft and even then only as far as Port Chalmers. These difficulties were compounded by a sand bar projecting northward from Taiaroa Head, meaning that ships leaving the harbour had to turn hard to the left or risk grounding themselves. There was also another gnarly curve in the area of Otakou, known to sailors as “Harington Bend”.

If you, like I did, are finding this hard to visualise, try sliding the diamond right and left on the image below. On the left we have and excerpt from the 1855 Admiralty Map, while on the left we have the latest Google Maps satellite view, providing a hopefully-helpful comparison between then and now.

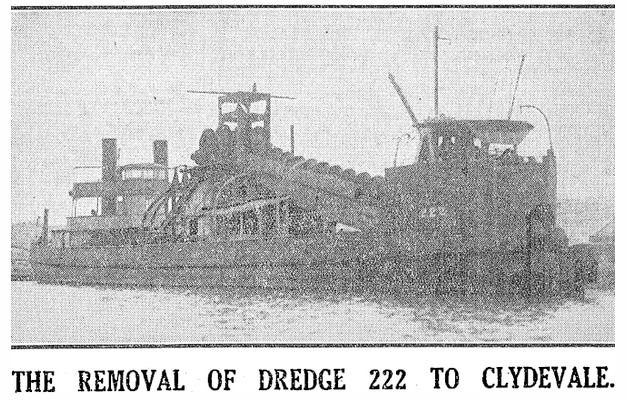

The plucky settlers, so reliant on imports and exports, were determined to transform this sand-trap into a world-class harbour. One way to approach the issue was dredging, which the Provincial Council (whose efforts over the years passed to the Otago Harbour Board, and today belong to Port Otago) began with the dredges New Era in 1868 and Vulcan in 1877. These two first dredges mostly focused on deepening the berths in the harbour basin, and it was the 222 in 1882 which was the first to be able to work on the harbour entrance.

Unfortunately the geography of the channel meant that dredging was a losing game, as the tides brought in more sand than they took out, resulting in a net gain of sand moving up the harbour with every high tide. This required an engineering solution – and so The Mole was conceived.

Originally known as Cargill’s Pier, the work was started in 1884, with the first structure completed in 1888. Its effect on the sands was considerable, training the tide in such a way that the Taiaroa sand bar was shifted into a more northerly and out-of-the-way position. On the other hand, caused the beach on its western side to grow while the Aramoana spit shrank alarmingly. You might think this was good for shipping, but it put the waters in “a state of unstable equilibrium”, shifting the deep water channel east toward Harington Point and preventing deep-drafted ships from entering further into the harbour.

How, then, to solve this new problem? Harbour Board John Blair Mason tackled the problem in 1905. At his direction, a rubble “training wall”, designed to redirect the movements of the tides, was built in a north-south direction along the end of the spit, with a series of groynes running from the high tide mark out to the wall. Groynes too were installed jutting out from the peninsula side around Otakou, to siphon the tide back toward the middle of the channel.

The most northerly of said groynes was, in fact, what we were currently standing on, and is said to have done an admirable job at “arresting” the shifting sand, while sand-catching fences and later vegetation were used to build up the height of the spit. This resulted in a deeper channel and less buildup of sand around Harington Point, restoring the path for larger vessels.

Okay, but what’s with the buckets? Our early settlers were a waste-not-want-not bunch, and not opposed to tossing all sorts of things into the drink if it could fill space. In the case of these groynes, that included old pipes and dredge buckets. Since said buckets were property of the Harbour Board, it’s not a stretch to hypothesise they came from one of the harbour dredgers. 222 seems to be the prime candidate, as her buckets were replaced in 1901.

With the movements of the sand properly pinned down, the dredgers were able to straighten the route and carve out the Victoria Channel we know today. The “toe” of the spit does appear to be suffering some erosion of late, judging by the unearthing of these buckets and the great hollows carved out of the dune behind.

As for 222, she served for 50 years before being superseded by the Otakou. She was sold to a mining company for use in gold dredging, but the company didn’t last. Her final resting place was not far from here, as in 1936 she was scuttled next to the Mole alongside several other shipwrecks, to buffer the structure from the tides.

We continued around the toe, passing the largely-deconstructed Pilot’s Wharf

On the sheltered inner side of the bar we were greeted with the expansive sand flat, good for collecting shellfish on occasion. There’s a curious feature here too, a long straight ridge of basalt cutting across the sand. This is what remains of the railway line which once stretched from Pilots Wharf to the Mole, helping to transport materials to the construction site.

Naturally there’s no longer much need for such a service, and both the wharf and the railway are melting back into the environment.

As for us, we soon found ourselves back where we started and ready to head home for warm cups of tea – lest another storm come in and wash us away with the sand! What will the coming years bring for this delicately-balanced landscape? Only time and the winds will tell.

References:

Inshore Dredging Disposal Monitoring Factsheet – Disposal History

OTAGO INSTITUTE. Otago Witness, Issue 3145, 24 June 1914, Page 7

THE LOWER HARBOUR. Otago Daily Times, Issue 11189, 11 August 1898, Page 3

The Evening Star WEDNESDAY. DECEMBER 6, 1905. Evening Star, Issue 12679, 6 December 1905, Page 4

HARBOUR BOARD REPORTS. Otago Daily Times, Issue 13424, 26 October 1905, Page 11

HARBOUR BOARD REPORTS Otago Daily Times, Issue 11979, 28 February 1901, Page 7

HARBOUR BOARD REPORTS. Otago Daily Times, Issue 12158, 26 September 1901, Page 9

DREDGE 222 Evening Star, Issue 26011, 28 January 1947, Page 6

FIFTY YEARS’ SERVICE Otago Daily Times, Issue 22200, 1 March 1934, Page 5

THE WORKS AT THE HEADS. Otago Daily Times, Issue 7336, 20 August 1885, Page 3

we are currently fighting to have the training wall maintained as the backwash from current shipping is devastating the dune protection for the ecological area .An existing groune needing simples maintenance

Thanks Paul, that’s helpful to know what’s going on. We definitely seem to be losing a lot of sand from the “toe” area.

Thank you Paul for this research. I was looking for a photo of the original Pilot house as my grandparents lived there for a time while he managed the dredging project maybe about the early 1930s. He was Les Coxhead, a mechanical engineer with the Harbour Board from 1924 to 1963. The house was very basic with no hot water and my grandma had 2 young children to care for.

Thank you so much.

We walked out on The Mole today. I was fascinated and wondered about its purpose and construction.

This is the only information on its history I could find.

The overlapping illustrations with little drag diamond were brilliant (once I worked it out!)

Cheers

Eric