I’d been back in Dunedin a week or two before I proposed an adventure with my good friend KL from KL’s Self Discovery. We decided on an old Otago classic, the famous Moeraki boulders north of Dunedin – I’ve been there before but not in many years. Studying the weather forecast we selected the least awful-looking day for a day out.

Unfortunately the least-awful day dawned in an unpromising manner, with thick grey cloud hanging low. Unwilling to abandon our adventure we decided to hope the weather would hold as we headed north with KL’s three kiddies in the back. Almost immediately our hopes were dashed as rain splattered the windscreen, but we pressed on regardless.

We passed Waikouaiti and the turn off for Johnny Jones’ pioneer farming settlement of Matanaka. Later the steep cone of Puketapu capped by MacKenzie’s cairn came into view as we approached Palmerston with its antique bookshop and delicious pies. And in short order we found ourselves passing Shag Point with its seal colony and derelict undersea mine shafts.

Then we cruised along a familiar coastal road, with macrocarpa-clad rest area that I recognised from many family outings. Not long after we reached the signposted turn off for the Moeraki boulders and parked up in the lee of the visitor centre. We fussed about ensuring that all the children were clothed appropriately for the foul weather before cautiously leading them across the parking lot. Little Theo, the youngest, was very keen to point out the “bus! bus!” but we were more concerned with ensuring the bus!bus remained far enough from the children for our comfort.

Passing the visitor centre we were a little surprised to see a sign requesting koha beside the path down to the beach. I’d left my wallet behind so it had to go unpaid as we followed the well-maintained gravel track which culminated in a steep wooden staircase slick from the rain.

I left KL to slowly accompany Theo down the steps (he wanted to do it himself) and forged ahead to the famous scattering of perfectly round boulders in varying stages of decay and sand-burial. Some were almost covered, some riddled with cracks and some had burst open to reveal the orange crystals that lined their hollow insides.

The boulders are a fascinating natural occurrence, called “concretions”, formed in sedimentary deposits when a cementing agent begins to solidify around a nucleus – usually something like a leaf or tooth or fossil. The ones at Moeraki are unusually large, and it would have taken them between 4 and 5.5 million years for them to form in their ancient mudstone layer, cemented by calcite.

The Moeraki boulders also feature septaria, a fancy term for “lots of cracks”, although it is a mystery how they were formed. These cracks allowed fresh water to leach into the boulders and form crystals on the interior.

When KL and the kids finally caught up to me I pointed out one of the shattered boulders and encouraged the children to “Touch the, uh…pointyness?”

Turns out the term I was looking for was “scalenohedral calcite crystals”. I looked up “scalenohedron” to find that it is “topologically identical to a 2n-bipyramid, but contains congruent scalene triangles”, and that was the point I gave up on trying to describe it in layman’s terms. It’s a kind of shape, okay?

The Otago Maori have a more interesting story to account for the presence of these boulders. It all started with the canoe Arai te Uru which was sent to Hawaiki to fetch kumara, which showed more promise as a starchy staple than the native cabbage tree roots which could take two days to steam into an edible form.

On her return journey, Arai te Uru dropped off some of her precious cargo in the North Island and at Kaikoura. But as she made her way further south she was battered by a succession of huge waves and some of the baskets were washed overboard to end up on this beach – giving it its Maori name, Kaihinaki, or the food baskets.

More landed at Katiki beach just north of Shag Point, and long-time readers of this blog may well recall the fate of the stricken canoe, because we have already visited the site of her wreck on the reef off the coast of Shag Point. We have also encountered two of her passengers, Aonui and Puketapu, transformed forever into stone as they searched for resources.

Tales such as this were incredibly important for the southern Maori. They transmitted important knowledge about the land, such as the dangerous sea conditions of the eastern coast and the fact that kumara could not be grown in the deep south. And since the Maori did not possess European-style maps, these stories provided an understanding of the local geography and how various places related to each other.

I for one can attest to the effectiveness of this method! Since I started this blog, learning the stories of the land and relating them to one another, I’ve gained a much greater understanding of the way everything fits together, much better than I’d ever gleaned from a paper map. Just look at how I used “my” places as touchstones on our journey north.

Now that the whole team had arrived, I discovered an unforeseen issue – the kids were so fascinated by the stones that I was having difficulty getting any child-free pictures of them. But I could not bring myself to say: “Stop enjoying these fascinating natural wonders, I need pictures of them to put online!”

So I decided, with their mother’s permission, that it would be even better to have pictures that showed the magic of the little ones interacting with something they’d never seen before.

I’d been worried about how they might handle the persistent rain, but they were having the time of their lives, especially little Theo who pushed back his hood and was determined to get as wet as humanly possible.

We found a broken-open boulder that everybody wanted to try standing inside. Just as I was contemplating how many children I could feasibly stuff into a boulder their mother arrived to take charge of the situation.

In fact the only trouble we had was in convincing the kids that it was time to move on.

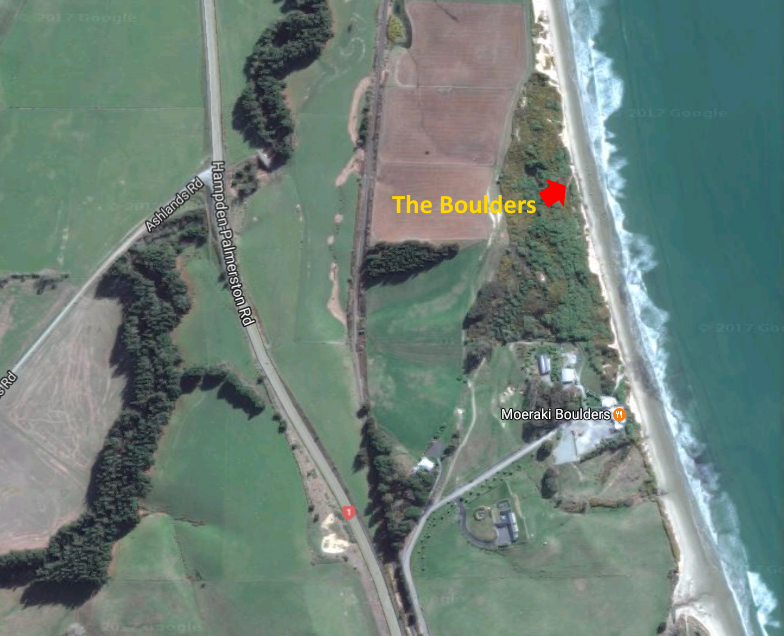

We climbed another set of steps at the other end of the beach, which took us on a short forest walk along the top of the small mudstone cliff from which the stones had slowly been emerging. From up here there was a convenient view point.

Then it was out past some lovely flowers and back to the car park. We had a quick drink in the warmth of the visitor centre café before successfully avoiding the buses for a second time as we returned to the car. Despite the rain the outing had been a valuable experience for us all!

References:

The Welcome of Strangers: An Ethnohistory of the Southern Maori by Atholl Anderson

2 thoughts on “Washed Up on Moeraki Beach”