Heading down from Auckland once again, this time in a shiny new Jeep, I searched for historic places to hit up on my way south on State Highway One. There were a great deal of sites related to the Waikato War, but one stood out as having a story not only fascinating, but easily accessible to a person like myself who has little familiarity with this period in our history.

I followed my phone’s automated directions toward Pukekohe, but turned off on to Runciman Road shortly before reaching the southern satellite of Auckland and parked up on the gravel verge next to a low stone wall. What I saw from my parking space was a quaint little wooden church painted a cheery yellow and set next to a tidy cemetery on a gentle slope. The surrounding grassy fields interspersed with sheltering pines and macrocarpas only served to enhance the impression of idyllic rural quietude. Perhaps this is the very life the first European immigrants – who arrived from Scotland and Cornwall starting in 1859 – hoped for when they began to settle this district.

Strangely enough, this is also how the Waikato District, then controlled by a powerful confederation of hapu united under the banner of Waikato, was described in the period before it was riven by war. Here the Māori were peaceful and prosperous, growing wheat which fed the growing settlement at Auckland and was even exported as far as Melbourne and San Francisco. The Waikato were friendly to Europeans; although paramount chief Te Wherowhero declined to sign the Treaty of Waitangi he declared Auckland under his protection during the Northern War against Hone Heke. The Aucklanders even had a house built for him in Auckland Domain.

If things had been allowed to continue in this manner, the colonial European dream of a creating a utopia of racial harmony as they carried the Māori along on a wave of civilisation could for once have been realised. But it was not to be so. How did things go from harmony to invasion and conquest?

Alarm at the Kīngitanga movement and the presence of Waikato participants in the Taranaki War eroded settler trust in the Waikato Māori. Frightening rumours ran rampant on both sides – an attack on Auckland was imminent, the Government intended to extend the Taranaki conflict into Waikato. Governor Grey did not help to restore trust during negotiations with the Kīngitanga by simultaneously fortifying the northern bank of the Waikato river and extending “the Great South Road” further toward the King’s frontier.

On 9 July 1863 the Government issued the ultimatum to all Māori residing in the area between Auckland and Waikato: Swear allegiance to the Crown or leave the district. Thus the ranks of the Kīngitanga were swelled by previously neutral Māori who saw no other choice but to abandon their homes in this suddenly hostile territory.

Crown troops proceeded with the paradoxically “defensive” invasion on the 12th, followed by a final ultimatum to the Waikato tribes back dated to the 11th. Though the Māori King refused to bow to the laws of the Queen he was still bound to those of causality, and thus was unable to respond in time to prevent open war. As the Crown forces advanced south toward the Kīngitanga capital of Ngaruawahia they left their delicate supply lines, stretching via the Great South Road back to Auckland, open to disruption.

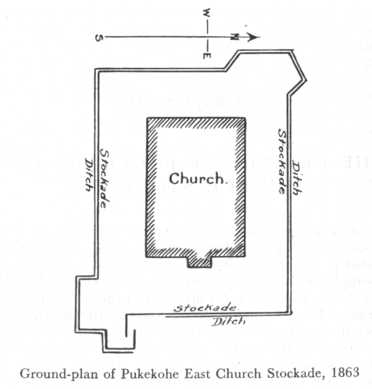

The settlers of this district came together to form a contingent of Forest Rifle Volunteers and began to fortify this position, building a wooden stockade around the church and digging a trench around the stockade.

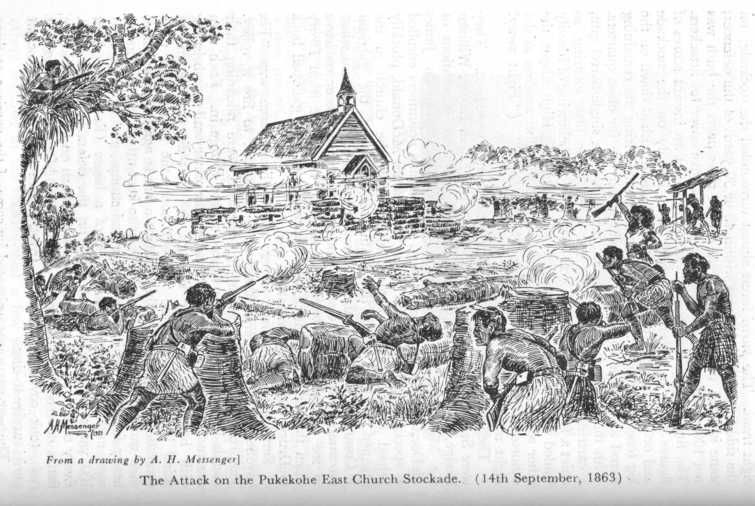

The stockade had yet been completed by the morning of 14 September when a force of mainly Ngāti Maniapoto and Ngāti Pou (whose territory this had been) came up from the volcanic basin to the south. The motley crew of settlers and special constables, numbering 17-19, abandoned their half-cooked breakfast and ran into the unfinished stockade, fixing their bayonets through the loopholes to counter the heavy fire now coming from the surrounding trees.

At this point in my investigation Thomas, a member of the trust that looks after the church, appeared on scene to unlock the place. He was delighted to hear the reason for my visit and proceeded to point out a detail that I’d so far missed – the defenders’ trench is still just barely visible.

The section I’d located belonged to the gateway of the stockade, its jutting design allowing the defenders to better cover their southern flank. The crucial job of defending this gate fell to Joseph Corbett Scott and James Euston. Joseph was a settler here, and though he later moved to Epsom he returned to Pukekohe East shortly before his death in 1940, drove his stick into the ground and declared “Bury me here!”

He was the last veteran of this battle, passing away at the age of 102.

There are other signs here too. Here and there a little round hole can be found on the church façade, marking a spot hit by musket fire, perhaps from an attacker who had climbed up a tree in order to counter the defences. In at least one case the musket ball itself had remained embedded in the wood until very recently, as Thomas showed me photographic evidence on his phone of one that had been discovered during maintenance work.

Thomas then came to my aid again, pointing out the headstone of Betsy Hodge in the far corner. Betsy, he told me, died in childbirth in 1862 and at the time of the battle this was the only headstone in the cemetery. The story checks out, as the New Zealand birth search confirms a Richard Hodge born around the time of Betsy’s death. Richard’s obituary records:

when he was only 12 months old he was taken by his parents into the old Pukekohe church, which was fortified and used by the white people as a refuge from the natives during the Maori war.

Other sources say that the settlers had already evacuated their wives and children, so I wonder whether this dramatic story had become embellished over Richard’s lifetime. What everyone does seem to agree however, is that Richard’s father William was among the defenders, and he’d also had a close brush while out scouting the day before the battle, spending almost an entire night in the bush evading the approaching Māori force.

William moved with Richard to Ruatangata a few years after, and met his end in a tragic manner. While chopping wood with Richard, now in his teens, he was accidentally struck in the head by his son and died from the wound.

As for the attacking side, sources vary wildly on the number of participants, from less than 200 all the way up to 500. Stories from both sides mention an older woman who fearlessly pressed the attack. The account of Te Huia Raureti of Ngāti Maniapoto, who was present at the battle, names her as Rangi-Raumaki.

Also present was Wahanui Huatare, who later became a prominent leader among Ngāti Maniapoto, doing all in his power in the wake of the King movement’s eventual defeat in the Waikato War to safeguard his people’s land and mana. He was raised a Christian and had previously been open to European innovations such as a mail service but became extremely disillusioned in the years leading up to the war. He allegedly brought bad luck on the war party by breaching an agreement not to loot settler homes when he raided the house of James McDonald on the way to Pukekohe. James and his son and grandson were behind the stockade, the little boy courageously fetching ammunition for the defenders.

The number of casualties suffered by the attackers is just as difficult to determine, as the Māori removed their fallen from the battlefield when they fell. On the way back south after the battle they interred the bodies in hidden places. The place where the six that were left behind are buried is marked by a boulder. Te Huia Raureti, many years later, guessed that upwards of forty had been lost.

Two members of the Pukekohe garrison had been away and were just returning when the attack began. They heard the gunfire and immediately rode for help to Drury. But the first reinforcements, arriving at about 1pm and just as the garrison were running desperately low on ammunition, were some thirty men of the 70th Regiment from Ramarama – their commander had heard the firing and directed the company to investigate.

Then from Drury came the 1st Waikato Militia, who skirmished with the Māori force in the area around the stockade. Finally the balance was tipped by the arrival of 150 soldiers from the 18th Royal Irish and the 65th Regiments. Fighting continued for another hour before the war party retreated.

The British lost three soldiers in the battle and eight more were wounded. Only one minor injury afflicted the small complement of settlers who had held the church for so many hours.

To the Pakeha this seemed a victory, and I suppose it does sound like one. But in the end the Māori may have achieved exactly what they’d set out to do. The King knew that his forces were outnumbered and technologically outmatched, but here they’d created a disruption in the middle of their enemy’s supply route and distracted a great many European soldiers, keeping them busy away from the front lines to the south.

And the strategy was working – the Government’s invading force was stalled to the south and unable to secure the quick decisive victory it had so eagerly anticipated.

I too had now achieved exactly what I’d come for, so it was time to bid my farewell to Thomas and make my own way south. Luckily these days it’s not such a perilous journey and this is no longer the disputed no man’s land it once was.

But still the green rolling hills seem haunted by the shadow of those days, as I traverse the length of the Great South Road and make my way down into the King’s bitterly-won heartland.

References:

The Great War for New Zealand: Waikato 1800-2000 by Vincent O’Malley

The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period: Volume I (1845–64) by James Cowan

100TH BIRTHDAY New Zealand Herald, Volume LXXV, Issue 23014, 16 April 1938

LATE CAPTAIN J. C. SCOTT New Zealand Herald, Volume LXXVII, Issue 23738, 19 August 1940

OLDEST RUATANGATA SETTLER PASSES Northern Advocate, 25 August 1937

Untitled Auckland Star, Volume IX, Issue 2511, 24 April 1878

PUKEKOHE STOCKADE Auckland Star, Volume LIII, Issue 84, 8 April 1922

Great research thanks. I used to live near the church and know a lot of its history. I think Richard Hodge’s recollection may be a bit muddled. I read somewhere once that Betsy Hodge “died in childbirth whilst her husband was away getting assistance”. The child lived and was a boy. They later moved away.