The town of Lawrence, Otago’s gateway to the gold fields, is one place I’ve always wanted to explore more fully. I acquired a taste when I examined the St Patrick’s Hall, but the Irish Catholics who built it were just one of many diverse groups who converged on the town in those heady gold rush days. When I saw an article on my news feed regarding the proposed restoration of the tomb of Sam Chew Lain in Lawrence Cemetery, I decided that this was my sign to look deeper.

I got in contact with Adrienne Shaw, herself a descendant of the Lawrence Chinese community and organiser of these noble efforts. An energetic woman, she was very passionate about her cause, and quite happy to share her research with me for the purposes of this post.

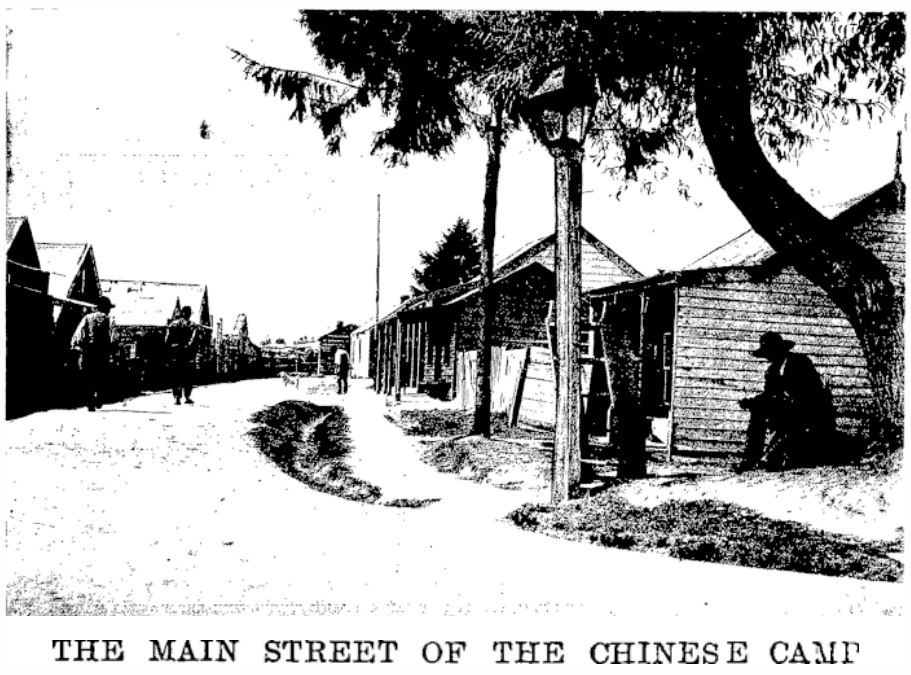

So we set off on a clear winter day for a town I often passed through but rarely stopped to explore. Upon arrival we cruised slowly down the main street right to the end of the town, beyond the outskirts and down the highway just a little more. Here we found the site of Lawrence Chinese Camp, where once a community of about 120 residents, mostly men, had made their home while they sought fortune in this remote country so far from their birth place.

There’s not a lot left here now, after the last resident died in the 1945. Just an empty field and three buildings. But during the 1870s this was the largest Chinese settlement in New Zealand, so lets take a look back in time to trace the history of this remarkable place.

My first surprise was to discover that the Chinese prospectors were actually invited here by the Dunedin Chamber of Commerce, eager to find a source of reliable and cost-effective labour to re-work the tailings since abandoned by European miners. This fact seemed rather at odds with what I’d learned in school about racism toward the Chinese in early Otago.

While bigwigs in Dunedin may have liked the idea, the locals of gold mining towns like this one were considerably less enthusiastic. Nevertheless the Chinese came, reaching a peak of 5000, mostly from the Canton region. Many had worked the goldfields of Australia prior to their arrival in Otago.

This camp was established in 1867, when the Lawrence Borough Council banned Chinese from working or living within the confines of the town proper. The ground here was originally waterlogged but the residents worked diligently to build drains and add topsoil until it was no longer in danger of flooding. At this important stop on the goldfields trail the town sported many amenities, including Chinese merchants and doctors, eateries, and two “Joss Houses”. One of those has been returned to its original home after having been moved into Lawrence for a time.

“Joss House” is a European term for these buildings which were not well understood outside the Chinese community. In reality they functioned more like a town hall, with a meeting space, altar, and space to care for the ill.

The Chinese, surprisingly, did not seem overly put out by being segregated from the town proper. They made few efforts to integrate into European society, for in general their goal was to earn enough money from work in New Zealand to return to China and purchase property. In fact, there are still houses built with Otago gold to be seen in China today.

But not all followed the standard pattern, as we shall see upon turning to the red brick building behind us. This is what remains of the Chinese Empire Hotel, a popular rest and watering place run by none other than the famous Sam Chew Lain himself.

Sam was born Chung Tsau Lin in 1840 at Sin Lin, Canton, China. The second son of a large impoverished family, he was nicknamed “the hungry son”. At 15 he left home for the Victorian gold fields and by 1866 he had made his way here to the Tuapeka workings. This decision may have saved his life, as one acquaintance of his claimed that all Sam’s relations in China had been killed in the Taiping Rebellion. If that’s true, it may be the reason he chose never to return to China, and instead made a permanent home here in New Zealand.

Two major steps in this vein were completed in 1872. He became a naturalised New Zealander, and he married Scottish-born Amelia Newbiggins Peacock, whose family he’d become acquainted with back on the Australian gold fields. The next step was to go into a business more permanent than prospecting, so he became a partner in the Tuapeka Flat Hotel – later the Chinese Empire Hotel – and bought out his partner’s interest in 1881.

Now sole proprietor, he set about rebuilding the place in grander style. The new building was completed in 1884, described as a “commodious” single-storey brick building boasting seven “lofty, well-ventilated” bedrooms. The building that remains today is not the same as it was back then when it opened, being halved in size during the 1940s.

In 1889 the addition of a stable was completed to a design of Sam’s own.

Sam passed in 1903, and his resting place was our next stop. We made our way to Lawrence’s cemetery and traversed the frosty ground, easily locating Sam’s tomb which still stands out splendidly despite its current disrepair.

Not only does it stand out for its magnificence, it stands out too for its placement firmly in the European section, showing just how much he’d become a respected figure in Lawrence. His obituary serves to further emphasise this, noting that he would be mourned not only in Lawrence but across all of Otago, as well as by the Chinese community to which he traced his beginnings.

From here we turned down the hill toward the Chinese section of the cemetery. As we descended I was struck its sparseness. While the European section was packed with headstones and monuments, the Chinese area had only a smattering of austere markers.

This likely reflects the fact that so many Chinese were in Lawrence on a temporary basis, without family or other connections, and so when they died they were without without anyone to mark their passing with more than a basic burial. What’s more they would not have left descendants in New Zealand to maintain their graves.

Once I had made my way through the frost and fallen oak leaves, I noticed one headstone was slightly different. I couldn’t help it really – it was the only one that featured English text in addition to Chinese. That made Fung Ming Chew the only person buried here whose story I can touch upon today.

Fung Ming Chew (alternatively spelled Fung Ming Chow) was a 20-year resident of Lawrence who became a member of the local Presbyterian Church. This brought him closer to the Europeans at the cost of alienation from his countrymen. A prospector, he made his simple home on the church grounds, attending service regularly despite the language barrier.

It was his European friends who arranged for this headstone to be erected in his honour.

This was the last stop on our brief foray into the experiences of Lawrence’s early Chinese immigrants. While many who came seemed content to hold themselves apart just as the racist policies of the time mandated, there were some who chose to cross those boundaries. Fung Ming Chew suffered exclusion from the Chinese community for his choice to cross the line when he converted to Christianity and joined a European church.

Sam Chew Lain appears to have been more successful, becoming highly respected on both sides of the divide. However, as well integrated as he was, it does appear he was occasionally reminded of his status as an outsider. One story tells of his attendance at a dinner party held to discuss the “Chinese question” – in other words whether Chinese should even be allowed to work and stay in New Zealand – as one of two Chinese representatives present. I feel second-hand embarrassment just thinking of what that experience must have been like, but Sam reportedly handled this event with grace and charm.

The day had been enlightening for both of us. We’d been well aware of the hardships faced by settlers to these frontier gold-mining towns, but had barely considered the extra dimension that being in a minority group would have posed. These learnings are something to bear in mind today when our accustomed historical narratives are suddenly being re-examined with a more critical eye.

Preserving these places is one small step in the journey to creating a more complete picture of our history, a history which is complex and contains many truths – truths which might look very different depending on which side of the boundary you stand.

References:

Push to restore tomb to honour heritage by Richard Davison

Individual research by Adrienne Shaw

The remarkable journeys of NZ’s Chinese goldminers by Lydia Anderson

New Zealand’s Chinese Gold-Mining Heritage:(Re) Telling their Stories by Helena Huang, Joanna Fountain, Harvey Perkins

Interpretative materials provided on site

WEATHERSTONES. Otago Witness, Issue 2557, 18 March 1903

Local and General Intelligence. Tuapeka Times, Volume XVII, Issue 1082, 4 October 1884

SAM CHEW LAIN. Tuapeka Times, Volume XXXVI, Issue 5046, 18 March 1903

Local and General Intelligence. Tuapeka Times, Volume XXIII, Issue 1705, 2 July 1890

LAWRENCE BOROUGH COUNCIL. Tuapeka Times, Volume XXIII, Issue 1735, 15 October 1890

Great tour thanks

Hi

Sam Chew Lains Tomb now as Cat 1 status

Please email me ; onemadcow@xtra.co.nz

And I can email you the confirmation letter

Adrienne Shaw

Hi

Sam Chew Lains Tomb now as Cat 1 status

Please email me

And I can email you the confirmation letter

Adrienne Shaw