Predictably, as I headed south on my great road trip the weather got worse and worse. From bright sun and hot days in the North Island, to blustering winds in Marlborough, and now drizzling rain as I entered Canterbury. Still I wanted to make the most of my brief journey through the region, so I decided that no matter the weather I’d stop off at a place that was once the centre of Māori culture in the South Island.

I turned off State Highway One just south of the turn off to Waikuku Beach, where I’d camped with Dad a year before. The narrow dirt road didn’t seem to be leading anywhere auspicious, and I reached a right angle bend without finding the monument for which I was searching. I doubled back, this time to investigate an odd concrete pillar I had noticed poking up over a grassy bank next to the road.

I pressed my way through the unruly sodden grass cloaking the bank, shuddering as the freezing water seeped its way into my boots. From my new vantage point I observed what at first appeared to be simply an unkempt empty field, but closer inspection revealed undulations in the ground that might be the remnants of fortifying ditches and embankments. Despite the complete lack of signage, this appeared to be the place.

The background to the establishment of this pa was one of the many southward migrations of Māori times. This time it was Ngāi Tahu moving into North Canterbury in the 1670s, displacing the established Ngāti Mamoe as they went.

Kaiapoi pa was built in about 1700 by Tūrākautahi on the remains of an earlier Waitaha stronghold, and like Huriawa and Mapoutahi, was said to be built on a peninsula of land accessed by a narrow neck. On all other sides it was surrounded by lagoon and swamp.

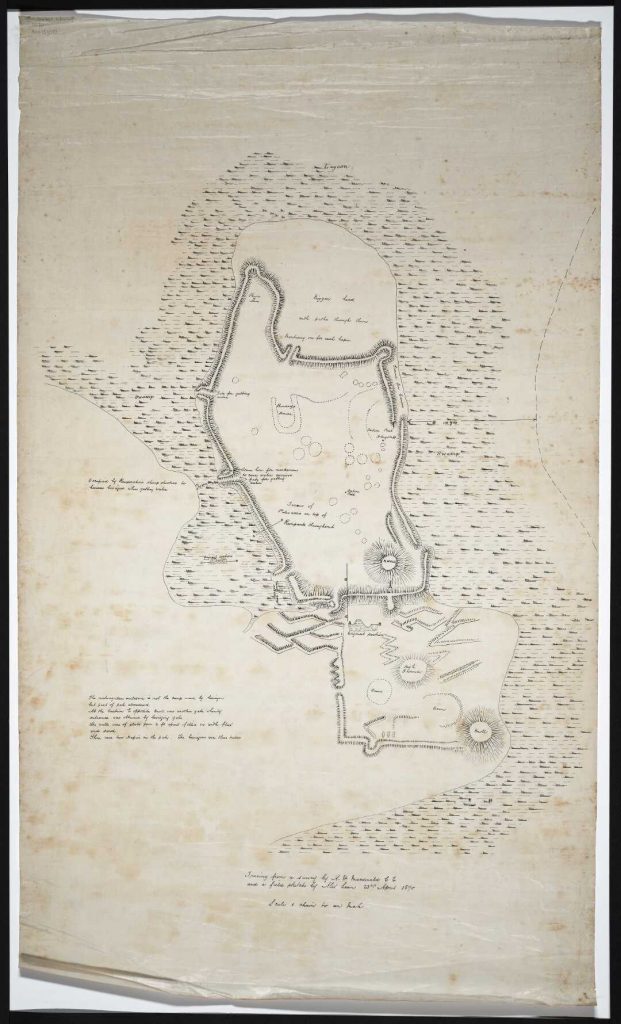

This did not jive with what I was seeing right now, as I saw no lagoon or swamp or peninsula. But an 1870 map of the pa confirms the tale – since those days the surrounding land has been drained for farming.

When criticised for his choice of abode, on the grounds of limited food supply, Tūrākautahi simply replied that kai (food) would have to be swung (poi) to the spot, hence the name. Some people still incorrectly think “Kaiapohia” is its true name, but this is in fact an insult referring to the piling up of bodies to eat.

Although a club foot prevented Tūrākautahi from taking an active part in any fighting, his brother Moki used it as a base for further raids into the south, and a route to the West Coast was established, sometimes used to peacefully trade in pounamu, at other times traversed by war parties. By the time it was destroyed the settlement had a population of approximately 1000.

Kaiapoi was prosperous, but another wave of southward migration was to bring its downfall. Te Rauparaha, pushed south by incursions into his own territory, was now bringing his musket-bearing warriors across Cook Strait. When this force arrived at the gates of Kaiapoi they claimed to be peaceful greenstone traders, but as alarming news of his depredations of their Ngāi Tahu kin to the north began to filter through the suspicious inhabitants launched a pre-emptive attack which killed eight leading Ngāti Toa and forced Te Rauparaha to retreat back to his Kapiti Island base.

But now the northern invader was determined to wreak his revenge. To start with he destroyed a pa at Akaroa by subterfuge – a story I’ll tell another day – but that was not enough, so in 1831 he returned to Kaiapoi with a besieging force which together with allies from Nelson and the West Coast may have numbered six hundred in total.

The people of Kaiapoi found themselves in a perilous position behind their palisades, for most of the men were away escorting visiting southern chief Taiaroa and his entourage. Though vastly outmatched, the old men and young boys left behind managed to drive off Te Rauparaha’s first assault. This gave the Kaiapoi men, accompanied by Taiaroa, time to return home and break their way back into the pa under the cover of night.

Now the conflict reached an impasse. Unable to gain the advantage by direct attack, Te Rauparaha’s men dug in to snipe at the defenders from under cover of a network of trenches. Taiaroa attempted to lead a counter attack, but that too failed to break the stalemate.

After Kaiapoi’s resident tohunga predicted the pa would eventually fall, Taiaroa chose to gather his men and leave the same way he had come – stealing through the swamp under cover of darkness. The Otago people, after all, had not had any hand in the act that had so enraged Te Rauparaha and thus had declined to send reinforcements to Kaiapoi’s aid.

Now standing alone, the Kaiapoi residents watched as Te Rauparaha’s trenches reached the foot of the palisades and his forces began to gather piles of dry brushwood. Their intent was clear – they would burn out the defenders.

A desperate measure was in order, and so under a favourable wind the defenders set alight the kindling, hoping that the flames would be driven away from their walls and the fuel would burn away harmlessly. But at a crucial moment the wind changed, and the move designed to save them proved to be their final undoing. As fire spread through the pa Ngāti Toa stormed inside and set upon the fleeing populace. Many were captured or killed, while some fled south across the swamp. Te Rauparaha pursued the refugees toward Akaroa, laying waste to several more settlements on the way, until better judgement deterred him from pushing any further into Ngāi Tahu territory. He returned to his Kapiti base, canoes laden with plunder and slaves.

The loss of Kaiapoi was devastating for Ngāi Tahu, and the southerners were faced with an influx of refugees from the north. Only slowly did settlers trickle back into the area, though never again was the site of Kaiapoi pa to be inhabited. There were a few attempts at reprisal, such as the doomed expedition that gave Measly Beach its name. Hostilities finally petered out around 1837, after Te Puoho’s disastrous attempt to strike at the heart of Ngāi Tahu territory.

Though this site was not to be inhabited, it was still considered extremely important to the local Māori . When the 1848 Kemp Purchase – in which Ngāi Tahu agreed to sell an enormous swathe of their land – was settled, the site of old Kaiapoi was guaranteed to be held in reserve, “sacred for both Europeans and natives”.

The monument – the mysterious object I had seen from the road – was erected in 1898, commemorating not the fall of Kaiapoi but the bravery of those who lived there. For the same reason a large gathering was held in 1931, the centenary of the battle of Kaiapoi, where attendees were given a history lesson and fed lavishly on dried eels and potatoes.

These days however, Kaiapoi seems largely to have been forgotten. The tekoteko (carved figure) which once capped the monument was removed after the earthquakes and is now kept in a museum. There’s no sign of the viewing platform that once served visitors, long since destroyed by vandals.

There are some who still try to keep this place cared for, but they are hampered by lack of funding, interest and manpower. It’s a sad statement on how little we care for the Māori part of our heritage that such an important historic site should go so neglected.

Who will gather here in one decade’s time, on the second centenary of Kaiapoi’s fall, to remember the deeds of Tūrākautahi and his kin?

References:

McDonald, Augustus Vanzant, 1842-1912. [Plan of Kaiapoi Pa] Tracing from a survey by Alex. Macdonald and a field sketch by Alex. Lean, 23rd April 1870]. [no imprint, 1870] [ms map]. Ref: MapColl-834.44941hkcmf/1870/Acc.5100. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/23148915

The welcome of strangers : an ethnohistory of southern Maori A.D. 1650-1850 by Atholl Anderson

SACKING OF KAIAPOI Evening Post, Volume CXI, Issue 141, 17 June 1931

The Story of Kaiapoi North Canterbury Gazette, Volume 2, Issue 4, 18 August 1933

SOUTH ISLAND MAORIS. Manawatu Standard, Volume IV, Issue 280, 27 October 1931

Degraded pa site lamented by Peter Hide