I was in England when the 2016 Kaikoura Earthquake struck my South Island home. It was hard to be so far from home during the most alarming seismic event in New Zealand since the Christchurch Earthquake, though thankfully the destruction was far less catastrophic despite destroying a good chunk of State Highway One.

I’d heard that the shake had made some radical changes to the coastline, and figured that since I was passing by on my way back home to Dunedin from my cursed road trip, I might as well check it out.

So south of Blenheim I found myself turning off on to Ward Beach Road. As usual whenever venturing off New Zealand’s main roads, no habitation was to be seen. I soon ran into a herd of sheep on the road, and was taken aback when the 4WD I’d presumed to be herding them merely passed by, leaving me with the flock. In trying to get around them I ended up driving them further down the road, for all intents and purposes as if I was now claiming ownership of this escaped rabble. I eventually managed to get by, only to turn the next corner and come face to face with several cows.

Lucky for me the bovine beasts paid me little notice, and I managed to pass by without further drama, heading for the great scarred heights of the limestone ridge which looms north of Ward Beach, which has been quarried for agricultural lime. This whole area was once part of Flaxbourne Estate, incorporated in 1846 by cousins in partnership Charles Clifford and Frederick Weld. Later the huge estate was controversially broken up by McKenzie’s policies.

I pulled up at the end-of-road parking lot and stepped out into the buffeting wind. A nearby sign warned me to watch out for ground-nesting banded dotterels, which I rather hoped I might see. Then I made my way carefully down to the stony shore.

Having recently read Charles Darwin’s Voyage of the Beagle, my head was filled with thoughts of the young genius as I approached the great rocky shelf ahead of me. Although at the time of writing Darwin had not yet developed his revolutionary theory of evolution, his travels in the geologically active regions of South America also caused him to question everything he’d ever learned about geology.

There were two battling explanations among Darwin’s contemporaries for the distribution of continents and the raising of mountains. One was based on a Biblical foundation, in which Noah’s flood was said to have accompanied a catastrophic rearrangement of Earth’s landmasses. This would explain how coastlines so far apart could fit together so well, why fossil seashells could be found so high above sea level, and why sediment had been deposited in so many thick layers. The other, described in a newly-published series by geologist Charles Lyell, suggested that gradual and ongoing processes were at work.

When Darwin reached the Chilean coast, he was given ample opportunity to observe the effects of frequent earthquakes and volcanism and make up his own mind.

As I watched Darwin make his observations and connect the dots on the idea of plate tectonics, I found myself wondering if I too could have come to the same conclusions. I like to think I’m pretty smart, but am I 19th-Century naturalist smart? Here’s my chance to find out – because I now have very similar evidence right in front of me.

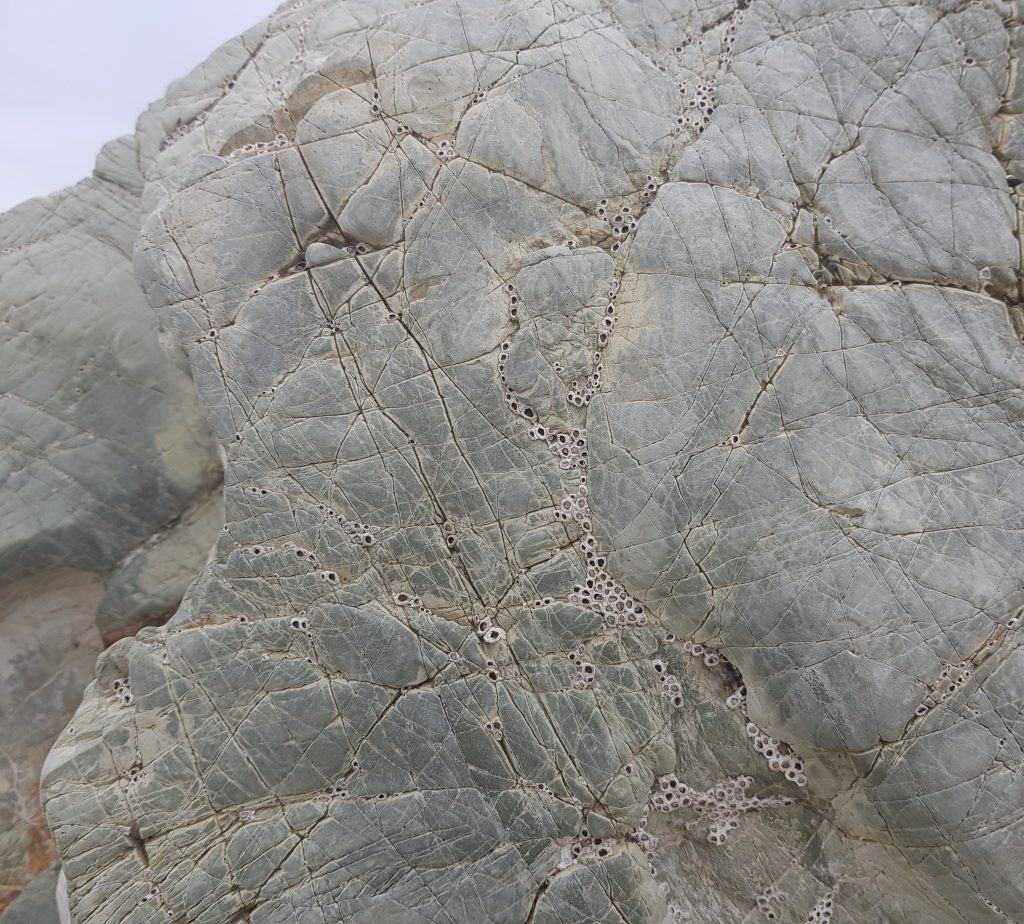

I approached the exposed rocks, noting a rather prominent white band encircling the outcrops. Up close, the white substance seemed almost like old paint.

I considered the phenomenon for a while and proposed my own theory: the white substance is what was left when the ring of kelp attached to the rocks was lifted above sea level. Most of the organic matter has now rotted away, but this strange sign remains.

Modern naturalists, with tools Darwin never imagined, have discovered a record of ancient quakes in the kelp populations that colonise a disrupted coastline. The kelp on an uplifted section of shore dries out and dies (along with whole populations of suddenly displaced sea life!), to be replaced by a genetically distinct variety. Meanwhile the nearby unaffected rocks keep their original strain.

I can certainly believe this as a place of cataclysm. I picked my way between great stratified hulks of stone upended and half-sunk. The newly-lifted slabs of rock were gnarled and furrowed yet surprisingly smooth to the touch.

The records of the people who settled Flaxbourne confirms the evidence of my eyes. The first recorded major quake to affect this area occurred in 1848, only two years after the estate had been established. This quake lowered the level of the lagoons at the Wairau river mouth by about 1.5 metres.

The next big shake was in 1855, and followed by numerous aftershocks. Several settlers fled their homes to camp in outbuildings, and Frederick Trolove of Kekerengu (not far to the south) commented of watching his house crumble from the relative safety of the woolshed:

I felt that what I had done in New Zealand was doomed to be undone in one night. So, indeed, was it too true.

In his diary he goes on to record hills denuded of vegetation by massive slips, new ponds and inlets created by subsidence, and a large wave which left his boat marooned on the grass some eighteen metres inland from its mooring. He soon discovered things were no better at Flaxbourne when he received the news that 16 houses had been destroyed there.

This quake lowered the coastal end of the Wairau Valley, allowing small steamers to navigate the lower Ōpaoa River and helping to establish Blenheim as a river port. But Blenheim’s gain was Flaxbourne’s loss as the mouth of the Flaxbourne River was raised, rendering a previous safe harbour unusable.

By 1888 geologists had managed to trace the offending fault from Wellington, across the Cook Strait, through the Flaxbourne Estate and over the Hanmer Plain.

Referring to it as a single fault was a little optimistic however, and by 1933 four Marlborough land blocks had been recognised, all capable of moving independently of each other – explaining how Flaxbourne could rise while the Wairau would sink.

Our modern understanding has developed even further, and it is now known that Marlborough is home to a network of many faults all running roughly parallel to the Wairau River, which itself sits on its own fault line. In fact the 2016 quake may have set a world record for number of faults ruptured in a single quake, with 180km of surface fault rupture across 21 faults.

When all this evidence is put together – the changes in front of me combined with the accounts of past earthquakes, and the recent genetic discoveries – there can be no doubt about it. The uplift that occurred here in 2016 is part of a pattern of gradual landscape change, one which over enormous time scales has shaped our rugged islands. Of course, this is hardly a revolutionary idea for me – I was brought up with it the same way Darwin was brought up with the Biblical account.

But what if the evidence had told a different story?

Would I have taken the brave but risky path of Darwin and championed a new explanation, one that better fitted the facts? Or would I have followed the example of Robert FitzRoy, captain of the Beagle and friend of Darwin, who upon his return penned an essay insisting that the facts could still somehow be made to fit the old narrative? I could only hope I’d have made the right decision.

With weather worsening I proposed a new theory: a timely retreat and a hot cup of tea was in order.

I left the shaky coastline having learned not only a lesson of geology, but a lesson in humility, in careful observation and seeing for myself, and in the value of being willing to adjust my world view in response to new evidence.

My voyage was not yet over, and I had far to go.

References:

Life of a Pastoral Station by Joy Stephens

Story: Weld, Frederick Aloysius

Voyage of the Beagle by Charles Darwin

DNA from kelp records major earthquake that hit Otago about 1000 years ago by Paul Gorman

Life on the Fault Lines by Joy Stephens

AWESOME SHAKES IN TREMULOUS ’55. Otaki Mail, 8 July 1929

THE Recent Earthquake. Daily Telegraph, Issue 5323, 13 September 1888

Kaikoura earthquake ruptured 21 faults – that’s possibly a world record by Michael Daly

EARTHQUAKE PROBLEMS Press, Volume LXIX, Issue 20925, 4 August 1933

I enjoyed your article, having recently made yet another visit to Ward Beach, though the first since the Kaikoura event. The raised concretionary boulders were fascinating. Did you trudge a mile north as far as Chancet Rocks where the unidentified fossil remains lie in rows? A geologist from Canty Univ has written up the quake elevations at Ward, with photos. Well worth a read.