Once again I found myself aboard a train cruising through the French countryside, destined for the village of Le Quesnoy (pronounced almost exactly like Le Quinoa). I was leaving tourist-France and entering real France, where I wouldn’t be able to count on anybody speaking English or babying me along my bumbling way. This was all the more concerning as I hadn’t yet booked any accommodation and was relying entirely on turning up with my baggage and repeating the single phrase “Do you have a room for two nights?” until somebody gave in and let me have a bed.

Luckily, a combination hotel-restaurant was located very near the station and so I managed to acquire lodgings at Chez Ahmed, revelling in my private room after four nights in shared hostel dormitories.

I then made my way to the tourist centre, where the receptionist’s first question upon realising I was an English-speaker was “Where from?”

I needn’t have responded because she already had her hand on the only English language brochure available, specially designed for visiting Kiwis. New Zealanders, it seems, are the only foreign tourists Le Quesnoy regularly sees. Are you intrigued yet? I picked up a map and a second brochure, both in French, and retired to my lodgings to study for the night.

Next morning, bright and sunny, I set out towards the fortifications that guard the border of the town proper, a complex combination of walls and ditches which run around the town and give it a curious shuriken-shaped footprint.

Le Quesnoy has been fortified in some manner since at least the 14th century, being the regular target of invasions, sieges and occupations by many competing empires. The defence system that we see today was created after the town finally became part of France in 1654 (it had been previously been Spanish or Austrian but never French). I set off onto the 5km path that follows the line of the fortifications in a circuit of the town, starting out along the bottom of the ditch that separates the inner bastion from the outer wall..

There are occasional small tunnels in built into the fortifications, the purpose of which was not clear to me. Exploring inside, beer-can evience suggested they had been occasionally been the site of parties, but I doubt that is what they were originally intended for.

I left the dry moat at the Porte de Valenciennes, one of four gates into town. Crossing the road, I continued on the other side, where the moat was actually filled with water. A family of ducks was making difficult progress through the thick bright green water weed covering the surface.

The path led me through a concerning field of nettles before bringing me to another tunnel through the defences. At first it seemed as if the tunnel exit was barred, but it turned out there was another way out to the side which was visible only once I got most of the way through.

Once through, I had to stop a couple of walkers to enquire after the precise location I sought, only to discover it was in fact only a short distance ahead of me. I found it quickly and, for the first time in a month, stepped into New Zealand.

To understand how a piece of New Zealand somehow got itself into northern France, we have to go back to the penultimate occupation of Le Quesnoy by hostile forces. This occurred on 23 August 1914 when the town was captured by German troops, and the citizens suffered under harsh occupation for just over four years.

Barely a week before armistice, the New Zealand Division arrived in the area and was tasked with liberating the village although it was still held by 1500 German soldiers who had been ordered to resist no matter what. Taking the well-fortified town from the enemy without harming the innocent civilians within was a puzzle which required some Kiwi ingenuity to solve. Of course artillery would have made light work of the ancient and now largely obsolete fortifications but why wreck the place if it could possibly be avoided?

So the Kiwis cased the town, searching for weaknesses. The inner walls were too high to be scaled by ladder from the bottom of the moat, but they eventually located a narrow ledge near a sluice gate that their ladder could be unsteadily perched on in order to get over the wall. This place is supposed to be near New Zealand’s little patch of territory, so I cased the area myself and could only find one likely looking ledge.

From (probably) this point the New Zealand troops were able to quietly enter the village and take the German defenders by surprise under the cover of smoke bombs aimed at the ramparts. Once the enemy learned the walls had been breached they quickly surrendered and the town was free, much to the jubilation of its residents. Of the 93 Kiwis killed in action in Le Quesnoy, 65 are buried in the local cemetery, which I unfortunately could not visit as it was too far for me to walk.

Thanks to the unusual tactics employed to take the town and the respect shown to its residents, the Kiwi effort has been remembered by the locals ever since. Visitors from New Zealand have often been received for ANZAC day and Armistice Day, and many parts of the town have been named after New Zealand people and places.

And, as I have already mentioned, part of Le Quesnoy literally is New Zealand.

In front of this peaceful area, perfect for reflecting on the past, beyond the low wall inscribed with “From the uttermost ends of the earth”, a memorial has been installed on the inner wall.

Inaugurated in 1923 and loaded with symbolism, the monument depicts the Kiwi soldiers scaling the wall. Lady liberty stands by, brandishing the wreath of victory, and in the bottom left corner crosses commemorate the ones who fell.

Ferns (as a symbol of New Zealand) have been planted on the edges of the brook running along the moat below, and as I looked down I noticed a bird that looked a lot like a pukeko. Perhaps I truly am home!

Then the bird entered the water, floating away like a duck, and the spell was broken. Later I learned that it is what in the UK they call a moorhen.

I sat for a while in the bright sunlight, trying to imagine what this scene must have looked like a hundred years ago as the Kiwis fought for the liberation of this village.

Then I continued along the path, which took me up on to the grassy top of the inner wall, giving me an excellent view out over the green parkland surrounding the town.

From atop this bastion the path lead down into town (nowadays it is that easy to get inside) and on to the Avenue des Neo-Zelandais which took me through an arch into the centre of town. Other notable signs marked the Place des All Blacks and Rue Helene Clark. I passed by the town hall and site of the original castle that was once the seat of the local rulers.

I passed the tourist office again and exited the town by Porte Fauroelx (no, I can’t help you pronounce that), crossing a bridge over the moat and stopping only briefly to watch the anglers as they tried their luck. Then I stepped onto the hornwork, a triangular-shaped island added for extra defensive purposes in 1712 after the town had been overrun in only six days by an invading Austrian force and then taken back in seven by the French despite all of its walls and ditches.

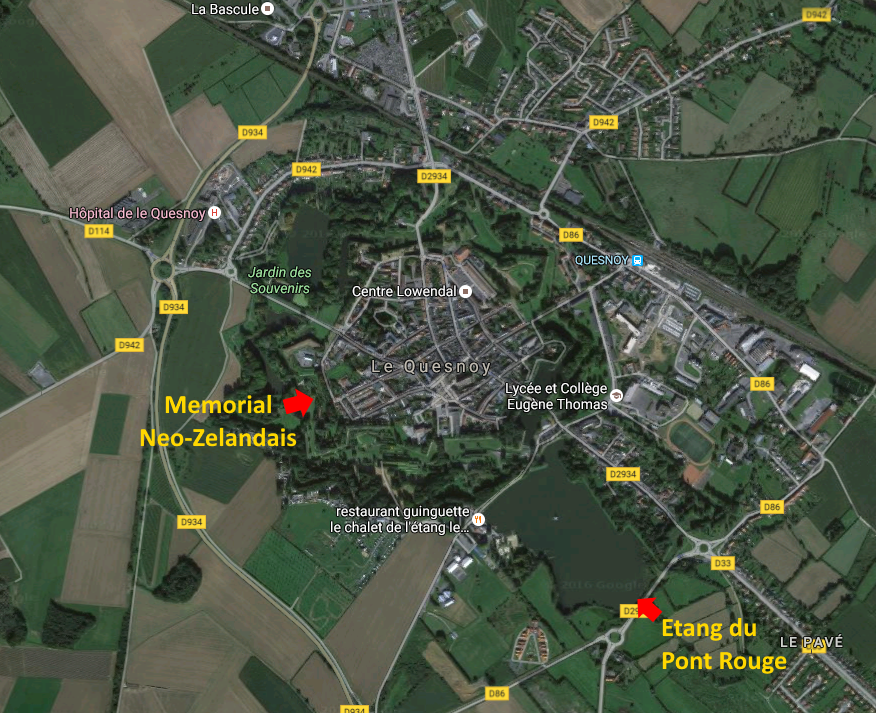

Beyond the hornwork you find Etang du Pont Rouge, one of two ponds created to hold water to fill the town’s moat when necessary. Currently this pond (or small lake, as I see it) serves as a fishing spot, activity centre and wildlife refuge. As it was still a bit too early for dinner, I decided to take a little wander along the shore line.

I discovered a family of ducks, a gaggle of geese, some clever fish hiding far away from the anglers, some pretty blue damselflies and this swan.

Having skipped lunch, I was getting pretty peckish, so I made my way to the nearby Le Carpe D’or restaurant and asked for a table. It was only 6pm so still far too early to eat (dinner tends to be late in Italy and France) but I was offered a table and the option of ordering a drink to pass the time. I checked the wine menu and noted the drinks were provided in measures of cl, which I presumed to be French for ml. Well, 35ml is not enough wine to get me by, so I’ll take the 75cl option.

I sat back, very proud of my ability to get by in French, and watched as my waiter returned. He produced a bottle of wine with a flourish and poured me a little to taste. Strange, but I know they take their wine seriously in France. I magnanimously approved the selection and found myself unexpectedly left with the entire bottle.

Said bottle, on closer examination, contained exactly 750ml of wine. Oh. My French skills weren’t good enough to explain my mistake, and I certainly didn’t want to be rude and waste all this lovely wine…so I concluded that the only possible way out of this situation was to pretend this was exactly what I wanted and drink the lot.

Perhaps that helped with my decision when I finally received the menu to try out the snails as an entrée. Besides, it was the first time I’d actually seen them available so I had to seize the opportunity. They came out scalding hot in a specially designed pot.

Trying them, I found the parsley taste to be a little overpowering. The snails themselves didn’t seem to have much flavour so I guess they’re one of those things that pick up the taste of whatever they’re cooked in, so if they’d been cooked in say garlic and butter I probably would have liked them a lot better.

I continued with another French favourite, moules marinières, a pot of mussels cooked in wine and served with fries. Since bread is served with every meal in France (and Italy) I enjoyed several chip-and-mussel butties, no longer particularly concerned with whether this might be considered crude.

Once all was demolished, I unsteadily paid for my meal and carefully made my way back to my room where I collapsed on the bed and waited in vain for the world to stop spinning.

Despite the over-abundance of wine, I did enjoy my visit to this quiet village of just over 5000 souls. I’ve come to the conclusion that I’m not much of a big city person so I enjoyed this break in the countryside. And it was great to see some familiar names, stand in my home country again and visit the site of one of the New Zealand troops’ most famous exploits.

Coming next: my last stop in France before moving on to the UK.

References:

Brochures and information provided by Le Quesnoy tourist office

Great finding a little piece of home in a far land…Tisk Tisk with the wine… did you sleep well? Looking forward to your next adventure as always.

Amanda,

I was sent a link to this blog page by Bill Harrington, who has written a book about Le Quesnoy based on letters and other material sent by Holly Wensley Spear to Bill’s mother. Holly served in the NZ Division and was among the first New Zealanders to enter Le Quesnoy after it had been liberated. Bill has asked me to help him produce the book, which we hope to publish in a month or so. The account of your visit to Le Quenoy is very interesting, and we shall certainly refer to it in the book. Also. with your permission, we may wish to use one or two of the photos in the book. I’ll send you a PDF draft of the book when it’s ready in a month or so (if all goes well!).

Bob Stoothoff

Rawhiti Editorial Services

Amanda,

We are now in the final stages of preparing Bill Harrington’s book FROM LE COLAC BAY TO LE QUESNOY for publication. Wishing to use your photo of the memorial garden in the book, we’re asking your permission to do so. The photo will appear on the same page as a photo of the Memorial Plaque. We’ll send you a copy of the book when it is published, we hope some time this month. Please tell the address to which we should send it. Thanks.

Robert Stoothoff

Rawhiti Editorial Services