My aim for the day was to find the site of a daring daylight highway robbery which took place during the Otago gold rush and caused panic in the city of Dunedin. My research indicated that it occurred in the bush above the village of Woodside, in a gully now known as “Sticking Up Gully”, not far from the 538m trig station. Well the station is on private land, so I’m not going to get that far, but most of Sticking Up Gully lies within DOC boundaries. There’s no track to the site, but how hard can it be? All I need to do is walk up Lee Creek until I get there.

Well the station is on private land, so I’m not going to get that far, but most of Sticking Up Gully lies within DOC boundaries. There’s no track to the site, but how hard can it be? All I need to do is walk up Lee Creek until I get there.

A flawless plan.

I set off down the southern motorway, left it at Mosgiel, and continued down Highway 87 through Outram. Not far beyond, I turned left at Woodside Rd, then right on to the narrow Ravensburn St. This took me directly to Woodside Glen, a grassy picnic area flanked by bush.

The town of Woodside is quiet now, but was more lively in the days of the gold rush, when travellers streamed through on the way to the Otago gold fields. It boasted a school, general store, mills and various businesses. The general store can still be seen at the corner of Woodside Rd and Ravensburn St, although it has been converted to a home.

By the 1880s business was moving to nearby Outram and Woodside began to decline.

Above me, the Maungatua range was shrouded in ominous white cloud. As we already learned, Maunga-atua is the great wave which battered the legendary canoe Takitimu of the Southland people, causing a man to fall overboard.

I started off along the track, which climbed steeply.

It all started on 18 October 1861, when a gold-seeker named Charles Corstophon was travelling up the Maungatua range, heading for the Otago diggings. Near the top he was confronted by four men, all armed with revolvers, who dragged him down into a gully and bound him hand and foot, pilfering his valuables as they did so.

Over the course of the day fourteen other men were robbed and brought down to the gully. Among the four highwaymen was a tall man, who gave the prisoners blankets to lie on as well as offering them tea, stolen whisky, and filling their pipes with tobacco over the course of the long day.

At sunset, each of the prisoners was tied to a different tree and the tall man covered them with blankets and tents for warmth. Then the villains departed. Eventually Corstophon and another prisoner named William Maloney were able to wiggle free and release the other prisoners, who had now been detained for as much as fourteen hours.

The newly-freed captives hastened down the hill to Woodside and the nearest magistrate to report the crime. In all, about £400 was taken.

The tall man, the one who had filled pipes and shared tea, was identified as Henry Garrett, a lifelong outlaw. He would become a legend and figure of much debate. Was he an unrepentant villain who resisted every opportunity to reform, or a sort of Kiwi Robin Hood, the tragic product of a horrific prison system who nevertheless acted with an odd sort of honour? I’m only the latest of a long line of people to ponder this question.

I soon reached Lee Creek, a narrow stream strewn with boulders and running between walls of tangled bush. All I had to do was head upstream.

As I slipped and scrambled and jumped from one boulder to the next, I reflected on the enigmatic character of Henry Garrett. He was described as unusually tall, with blue eyes and brown hair which tended to grey. There was a scar above one eyebrow and he walked with a shuffling gait, possibly the result of many years in irons. Although he had no formal education, the was keenly intelligent and taught himself to write eloquently. He scorned religion but knew his bible front-to-back as it was one of the few books provided in prison. It was a great source of stories, he said. In court he was theatrical, defending himself with threats and accusations of conspiracy. Throughout his life he carried a smouldering sense of injustice, blaming all of society for the cruelty inflicted by the harsh penal system.

He was charismatic and capable, a man who could have easily succeeded as a law abiding citizen. And yet he continued to turn to crime, spending fifty years of his life in various prisons.

I scrambled up a slippery moss-covered boulder that blocked my path, ducked a few fallen trees, and continued upstream.

Henry Garrett was born Henry Rouse in 1818, in the small farming village of Hose in Leicestershire, England. His mother died when he was very young, and by his own account his father was an abusive drunk (Garrett made many claims about his life, some decidedly untrue). He learned the trade of a cooper but by the young age of 24 he experienced his first run in with the law.

A gamekeeper confronted Garrett who was poaching on the land of a local lord, and a physical altercation ensued. Garrett was sentenced to three months imprisonment for the assault. Upon his release, he and his friends proceeded to terrorise the neighbourhood, culminating in the theft of several items from a linen shop. This would change his life forever, as he was caught and sentenced to ten years transportation.

He was first shipped to Norfolk Island, a hellish prison where convicts were worked ceaselessly and kept on the brink of starvation. Disease was rife, and any attempt by the prisoners to improve their circumstances was met with immediate sabotage. When they attempted to brew a kind of medicine for their constant illness, all their billy cans were confiscated and destroyed. The overseers were sadistic, and any complaint was met with a flogging or even worse torture.

Under increasing public scrutiny, Norfolk Island was eventually shut down and Garrett was moved to Van Diemen’s Land (now known as Tasmania). He was posted at the Cascades, part of the peninsula separated from the Tasmanian mainland by the 30m wide isthmus of Eaglehawk Neck – daunting prospect for any prisoner who might dream of fleeing, with its row of vicious dogs chained just far enough apart to be sure to maul anyone who tried to pass.

Garrett tried to work well to reduce his sentence, but a petty theft resulted in a heartbreaking eighteen months added instead. When gold was discovered in Australia he absconded despite being denied a ticket of leave, and by 1852 he was in Ballarat under the new name of Henry Beresford Garrett.

Here he cooked up a scheme with three other dodgy gentlemen to rob the local bank. They strode into the bank in broad daylight brandishing revolvers and bound and gagged the unfortunate staff. They escaped with booty to the value of £14000, a grand success!

Their freedom, however, was to be short lived. Garrett’s three accomplices were soon apprehended, and Garrett himself was tracked down to London and dragged back to stand trial in Australia. Despite roundly protesting his innocence, he was sentenced to ten years hard labour.

Thus began another miserable period in Garrett’s life, imprisoned aboard the prison hulks in Hobson’s Bay, Victoria. The food was measly and often rancid, the rooms barely large enough to lie in, and the prisoners’ clothing was taken away at night so that they would be denied even the small luxury of using them as a pillow. Any complaint resulted in “ringbolting”, a punishment in which the victim’s hands would be chained behind his back to a bolt about three feet above the floor so that he was unable to sit or lie down.

By his own account Garrett witnessed the murder of the cruel warden John Price, who was beaten to death by a mob of prisoners in a dispute over inedible bread. He made much of the idea that a little kindness – just a little bit of good bread even at the last minute – might have saved the warden from his grisly fate. Unbearable cruelty, he declared, is how the penal system turns desperate men into monsters. Perhaps that day on Maungatua he was proving a point?

When gold was discovered in Otago in 1861 Garrett had finally managed to obtain the coveted ticket of leave. He immediately took ship for Dunedin, robbed a gun shop, and joined up with three mates for the daring heist. A fortnight later he was back on his way to Australia.

He enjoyed only three months of freedom before being nabbed in Sydney and sent back to Dunedin to face trial. Despite his impassioned performance he was sentenced to eight years in Dunedin Gaol.

Prison in Dunedin was only marginally better. Lashes were still employed and Garrett was probably put to work levelling Bell Hill to prepare it for the construction of First Church.

After serving six years of his sentence he was released. The Dunedin police sent him to Australia, but he wasn’t wanted there either so they sent him right back. So he ended up working in his old trade of cooper at a local brewery, where by all accounts he was a good employee – a kind and generous man who was nevertheless inclined to hold grudges.

This worked out well…until he was caught in a seed store after breaking in and pilfering some small items.

It is strange how readily Garrett surrendered, almost as if he was resigned to his fate. What could have led him to throw away his new law abiding life for a few trinkets? Was he a kleptomaniac? Did he arrogantly think himself above the laws of society? Or, as some have suggested, could he simply not function outside of the prison system that had been his home for so long, and so deliberately arranged his return?

The judge was not inclined to be sympathetic, and handed down a sentence of twenty years. Garrett settled down to study and write from behind bars.

Garrett was strong, but finally his health began to fail. And so he was moved to the kinder climate of Lyttelton in 1881.

Then in 1882 he was released in Canterbury. He got a job a a cooper and I’ll give you a moment to guess what happened next. That’s right – nine months later he was back before a judge, having been caught in the act of stealing a bottle of wine.

Garrett was to die in prison, passing away in 1885 at the age of 67. His funeral was attended by the governor of the jail and six fellow prisoners. Thus ended the “strange and turbulent life” of Otago’s first bush ranger.

And here too ends my attempt to reach Sticking Up Gully, as I met an impassable wall of fallen rocks and tangled tree trunks over which Lee Creek cascaded. I had no choice but to turn back, and honestly I doubt I got anywhere near my target. If I want to visit the site of Garrett’s most notorious crime, I’ll have to find another way.

My adventure ends here, and I’ll leave you to draw your own conclusions on the mystery that is Henry Garrett.

References:

Calm days after goldfield heist

SUPREME COURT, Otago Witness , Issue 610, 25 January 1862, Page 3

RESIDENT MAGISTRATE’S COURT. Otago Witness , Issue 886, 21 November 1868, Page 4

The real Henry Garrett, 1818-1885, Aus. and N.Z. criminal by Lance Tonkin

The first New Zealand Bushranger by David McGill

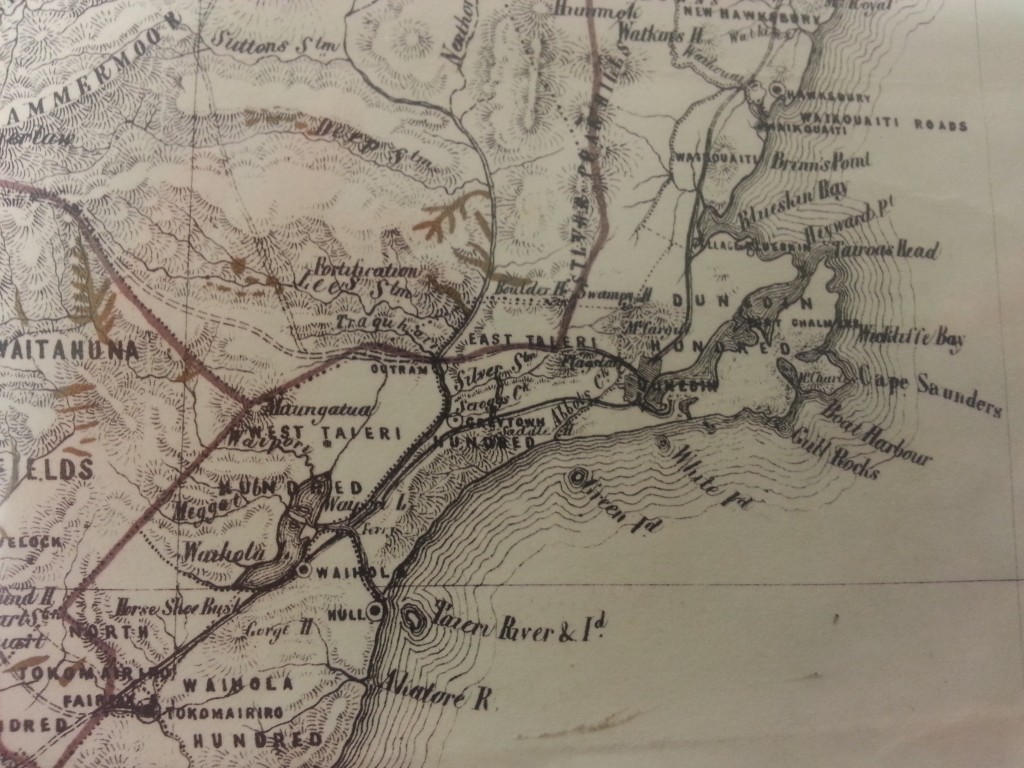

Papers and Returns – Map Of the Otago Gold Fields and sundry other maps laid on the table by the provincial secretary

[Archives Reference: R20351911 AAAC 701 D500 Box 14d/39a]

Dunedin Regional Office, Archives New Zealand, Department of Internal Affairs/Te Tari Taiwhenua

A great yarn…and a challenging walk..

You missed out this part of the story. The following extract from the book – Early Days in Central Otago, by Robert Gilkison tells an interesting tale: “The late George Calder, of North-East Valley quarry, had a narrow escape from being robbed on that eventful day. He was a boy of sixteen, and had to drive a dray containing over two hundred ounces of gold, worth some eight hundred pounds, to Dunedin. At one point of the road, where the track to ‘Sticking-up Gully’, as it is now called, branched off, Garrett had two outposts, who hailed all likely customers and advised them to take the short-cut down into the gully. Luckily the short track was not suitable for a dray, and the men did not suspect that a boy would be driving such riches, so they gave him a drink of water and let him go on his way. Only two men were ever convicted of complicity in this daring robbery—Anderson and the leader Garrett.” George Calder later developed the quarry in NEV and was a very successful stonemason in the City.

Thanks Allan, I didn’t come across that part when I was researching Garrett. Very interesting! I’ll have to check out that book.

No worries. Interesting reading a comment on the facebook article about a large deposit of gold found at base of the Outram bridge as the piers were built by George’s brother Hugh Calder and their father David built part of the top structure of the bridge.

What an interesting man! Great writing too. I really liked the way you wove the narrative of his life into your adventure – it was very gracefully done.

Thanks! It was tough to put it all together into a cohesive narrative. The one book I read that tried to do so wasn’t too great.

I have visited Sticking Up Gully. It is actually near the top of the ridge at 400m . The point is exactly north of the end of the red track line. However, it is easier to take to the ridge halfway up the red track and follow this to the little valley near the top. The old road takes a 90 degree turn just short of the Gully.

GPS -45.846252 170.166766

Thank you for the tip! I’ll have to make another attempt some time!