For my final English adventure, I decided to seek out a place I’d seen in many an online clickbait article – Tyneham, the Dorset town that has supposedly been “frozen in time” since 1943. The impression I got from these potato chips of the reading world was a remote abandoned place, shell-marked ruins reclaimed by the forest whilst the children’s books still lay open on their school desks. I resolved to see this place for myself, and committed to giving my readers a hearty meal of information.

From my home base near Stonehenge, I headed south into the county of Dorset. I turned to the east upon reaching West Lulworth and found the entrance gate to the Ministry of Defense firing ranges at a curve in the road just past East Lulworth. The range is still actively used for training purposes, and is only open to the public on weekends and public holidays.

Luckily I’d chosen a Saturday for my journey, so I was able to carry on along the narrow road winding up into the hills. The thick fog closed in around me, almost as if I truly was travelling back through the mists of time.

Stopping briefly at a lookout from which no view was forthcoming, I wended down into Tyneham’s wooded valley, eventually ending up in a large car park. Here I had my first view of the village which time forgot – apparently not forgotten by the maintenance man as the lawn was freshly mowed and a bright clean Union Jack was flying above the main street.

I placed my £2 in the first of several donation boxes – bylaws bar the Ministry from commercialising this place which prevents it from becoming a full-blown tourist trap, but that doesn’t stop them from begging for the village’s upkeep.

I headed straight for the first row of crumbling stone buildings, passing Tyneham’s phone box on the way. The village got its phone box in 1929, although this is not the original, which was destroyed by accident in 1986 during the filming of a movie. Sadly, I have not been able to find any further details on how the historic phone box came to be “flattened”, but the film company replaced it with an authentic recreation whose well-maintained paint job is a surprising contrast to the ruined buildings beside it.

Entering the first home in the row, I discovered that informational panels have been installed in all of the homes here telling of the families who last occupied them before the great government confiscation – saving me a lot of research!

The house at the end of the row was traditionally occupied by the local shepherd, followed by the Post Office which was cared for by a succession of postmistresses. Next came the labourer’s cottage, last occupied by the Whitelock family, and finally the house occupied by the school mistress.

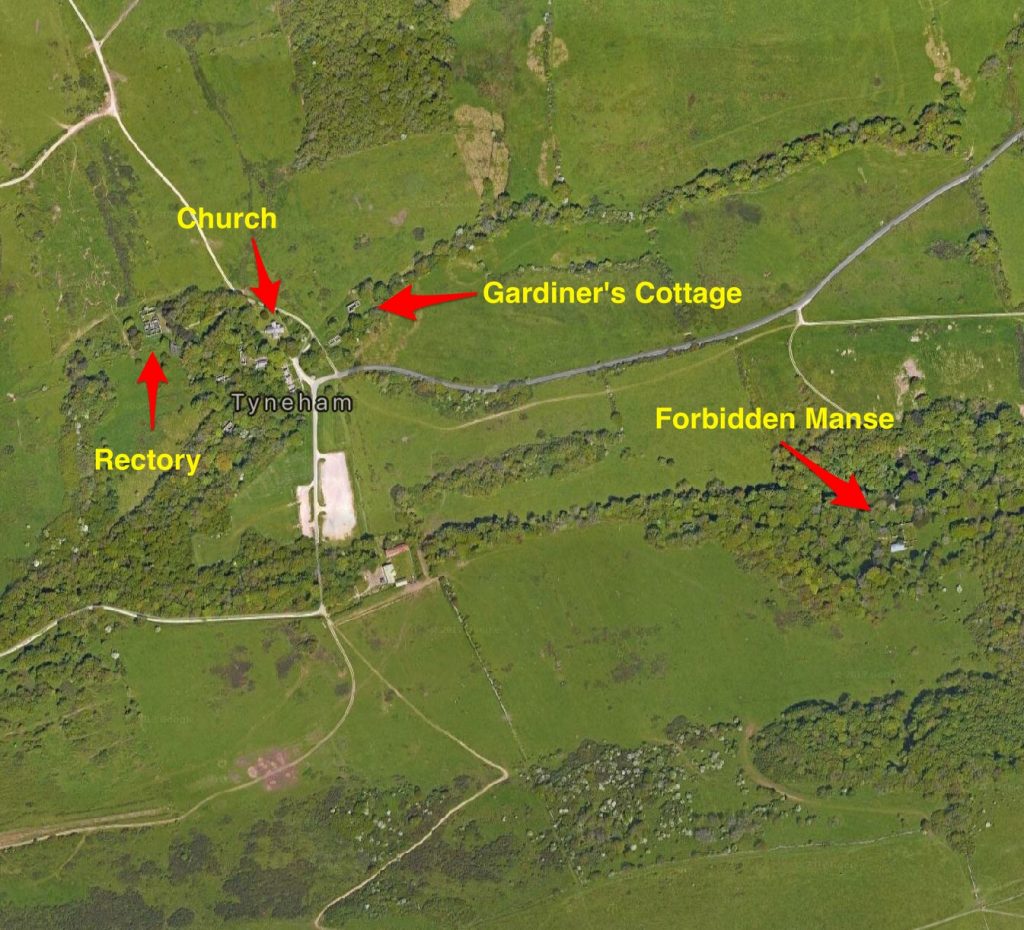

Beyond this little row, across the lane, stands the church – where the final note was hung by evacuating residents asking its new owners to treat their homes well and stating their intention to await the day when they could finally return.

Why was Tyneham taken? The date gives the clue – during the Second World War the War Office required the land for training purposes ahead of the D-Day landings, and so its 224 residents were given 28 days to leave – in at least one case this blow came just after being notified that a son had been killed on the front line. The confiscation was supposed to last only for the duration of the war, but the close of one very hot war heralded the dawn of a new colder one and the purchase was made permanent in 1948.

By now I expect that even if the village were returned to its previous occupants, very few would remain to come home.

The church itself dates back to the 13th century and has survived relatively unscathed. The Tyneham civil parish still officially exists, despite having a population of zero.

I tried the door and found it unlocked, allowing me to enter the building, now home to an exhibition showcasing the history of the village.

One of the most interesting features of the church was the 700 year old piscina, or stone basin used by the priests to wash their hands and ceremonial objects. Its rough-hewn stone was a contrast to the otherwise smooth interior walls of the church.

Leaving through the back door, I crossed back over the lane to the old school. Time to see the legendary abandoned schoolwork…which turned out to be another exhibition, set up when the school house was restored and reopened in 1994. In fact the school, opened in 1856, was closed in 1932 due to lack of pupils. Now it has been preserved as it might have looked in the 1920s.

Next up were the laundry cottages, the only homes in the village to have running water. All the other residents had to bring water by bucket from the pump near the church (next to a tree planted to commemorate the coronation of George V in 1910). I recognised the old fashioned laundry tub from similar ones I’d seen in the occasional Kiwi early settler ruin.

From the laundry I spotted another ruined building camouflagued in the wintry woods beyond. For the first time the experience felt like I’d imagined it, approaching a mysterious ruin through the trees.

These were the Gwyle cottages, once homes of the Wellman and Grant families, now just as empty as the rest of the town. I poked around, passed a picnic area and wended back around to the rectory, a large impressive building which had once been two stories but has now been reduced to one. I could only look longingly at it from a distance as it had been fenced off due to instability.

Having made a circuit of what appeared to be the only street in the town, I continued wandering in the hope I could find something more without stumbling into the military zone. Following another mown trail I found success as another derelict building loomed before me.

Here I found the cottage that had been home to the gardeners of Tyneham House, the grand 1523 manor that belonged to the Bond family, owners of Tyneham. The mansion was controversially destroyed by the army in the 1960s and its former location remains out of bounds to the public to this day.

The last gardener to live here was Tom Gould, along with his wife Virtue, son John and daughter-in-law Muriel. John was away serving in India when the village was requisitioned. For the rest of his life he campaigned for his right to return to the place where he was born. Sadly, it was not to be, as the success of the campaign was limited to the access now granted to the public on weekends and holidays.

Retracing my steps I ended up back where I’d started.

So Tyneham was not quite what the clickbait had lead me to believe, but it was fascinating none the less and well worth the day trip. But now it was time for me to leave the wooded valley and pass back out through the mists of time to modern day England. Soon enough it would be time for me to leave even England, marking this as my final adventure in this part of the world.

Until the next time I get the urge to go flying, of course.

References:

Interpretative signage provided on site

Good to know what is real and what is just hype…Another great yarn

I understand what you are saying, this is indeed an interesting topic right now. I often hear people discussing this at social gatherings. I have come up with an idea after reading your explanation. Cheer https://internet-installation.onrender.com