As I arrived in Lawrence for my investigation into the Chinese community that once lived there, I couldn’t help but be preoccupied with worldly current events. The ongoing Black Lives Matter protests and the conversations that had been sparked surrounding history, monuments and how we remember the past were all swirling around in my mind. Even my home town of Dunedin had felt the ripples of these changes, with the announcement that the Captain Cook pub would be renamed and even our own Robbie Burns statue being made briefly to wear a sign bearing the word “RAPIST”.

So when I stopped next to the statue of a prospector who I took to be Gabriel Read (though it’s not marked as such so could theoretically be any prospector) I thought to myself that surely this monument would be unassailable. There could hardly be any way that our legend of Otago’s famous father of the gold rush could be founded on racism or involve glossing over the work of non-Europeans in order to laud the white man!

Upon visiting the local museum the veil was torn from my eyes as I looked upon the brief blurb dedicated to “Black Peter”. Though I did not immediately rush to tear down the offending statue, I realised that there could be no better time to tell his story.

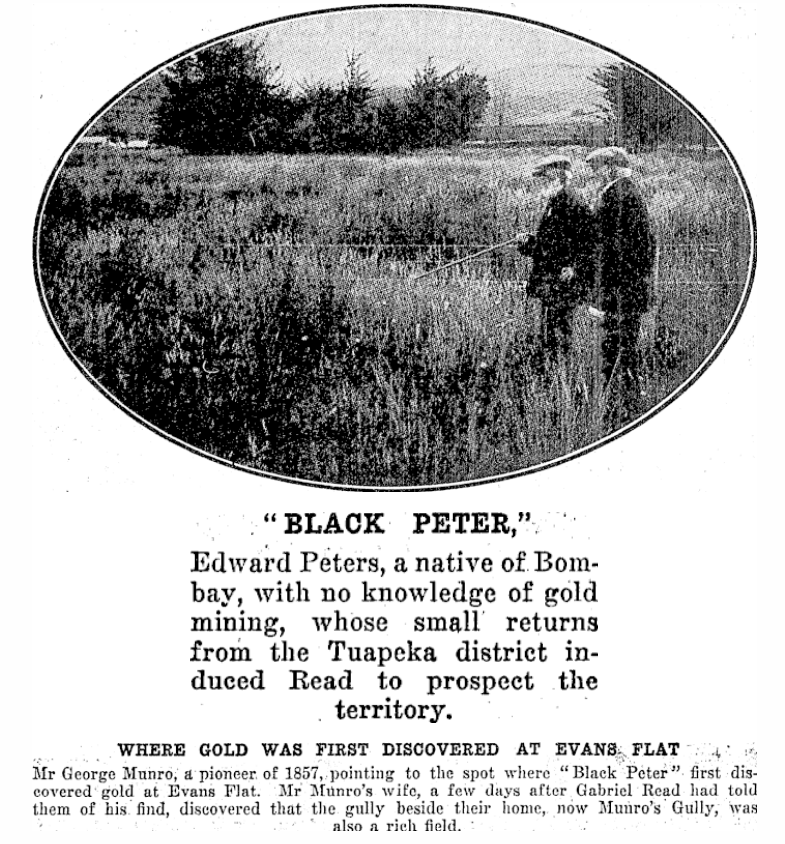

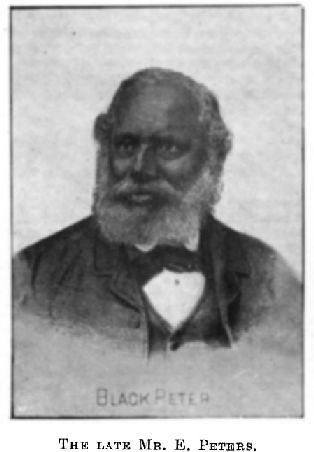

The man who would one day be unimaginatively nicknamed “Black Peter” harked from Mumbai (then known as Bombay) in East India and may have been the product of an interracial marriage, possibly half Portugese. In more official contexts he was called by his proper name of Edward Peters. Since there’s no surviving statement on what he preferred to be called, I’m going to try to be respectful and stick with ‘Edward’ here.

Not much is known of his life before he arrived in New Zealand, though it’s said he spent time on the Californian gold fields. He arrived in Port Chalmers in 1853 as cook aboard the Maori and jumped ship, turning himself in to the police a week later. I have to wonder about this episode, since everything else I’ve read gives the impression he was honest to a fault – it makes me feel like there must have been some extenuating circumstance that pushed him to abandon his employment, but if there was then it has been lost to history.

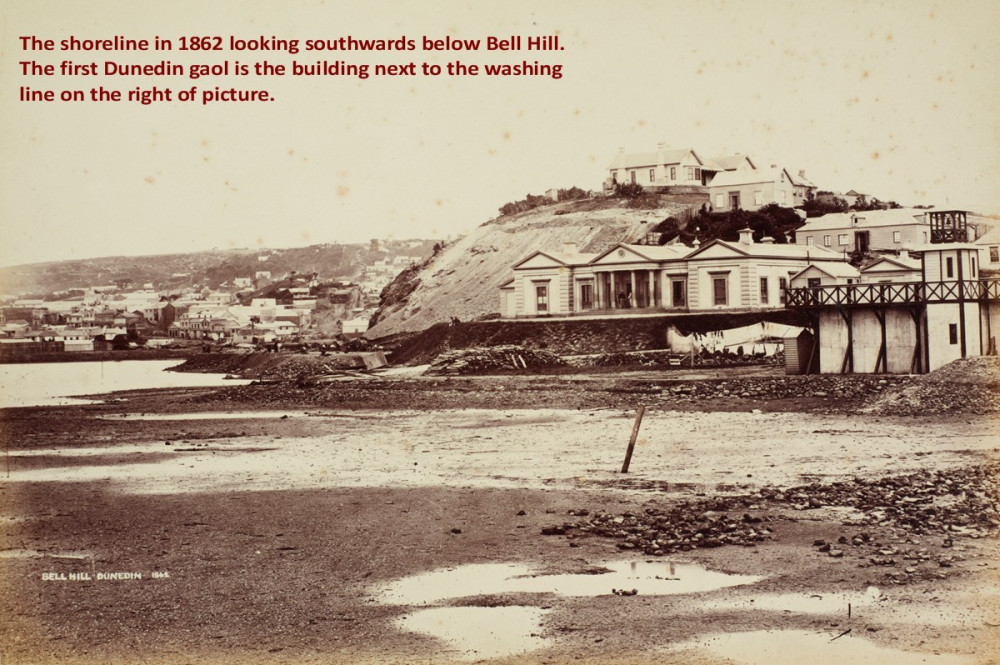

In those early days Dunedin prison arrangements were pretty informal, the jail being a simple and only somewhat secure wooden building. Edward Peters was sentenced to six weeks hard labour, which he is said to have completed by escorting himself to and from work sites without any supervision – see what I mean?

At this time the lands to the south and inland from Dunedin, especially around the Tokomariro River, were being opened up and settled. Once his sentence was done with, Edward – now in his late 20s – headed out that way to seek employment from the run holders, and was known to fossick about in the river near Glenore – though it wasn’t yet known by that name.

That was my first step on Black Peter’s gold trail, as I understood there was a monument to him somewhere in the valley, and I soon found it nestled in the half frozen grass of the Mount Stuart Recreation Reserve.

This was erected in 2009 (the 150th anniversary of Edward’s gold discovery), and opened by Governor-General Anand Satyanand, New Zealand’s first governor-general of Indian ancestry – a fitting touch, I think.

Feet well-soaked by dew and melting ice we returned to our vehicle before continuing to our next stop. This took us just past Lawrence to a locality known as Evans Flat. Today State Highway 8 bridges the Tuapeka here, but in Edward’s time it was a remote valley occupied by the Munro farmstead and teeming with wild pigs.

It was here that in the autumn of 1858, as Edward was finishing up a term of employment on Davy and Bowler’s run, that his oft-overlooked gold discovery occurred.

There’s a few different versions of this story. John Thomson, who was at the time ferryman at Balclutha (then called Molyneux), says that Edward came into town showing off a little bit of gold powder. Most people paid him no attention, but John was keen to accompany him to the place he’d found it and see if anything could be made of it.

Part way through their excursion they were also joined by a black American man (whose name John unfortunately fails to record!), and between the three of them they found small amounts of gold almost everywhere they tried. Unfortunately they were hampered by lack of proper equipment so John returned to his day job, intending to get together the funds for a proper expedition. But before he had the chance Gabriel Read announced his discovery and the rush was on.

In May 1858, after the excursion with John but apparently before the rush, Edward was moving a flock of sheep in the area with some companions. Come evening they set up camp by the river and Edward disappeared for a while, panning for gold. He generously offered what he found to William Dawson who had it made into a ring for his wife – said ring can now be found in the Otago Settlers Museum.

There’s long been controversy as to whether and how much Edward’s find inspired Gabriel Read’s own prospecting, leading to the ‘discovery’ that would have him go down in Otago’s history and enable him to claim the reward for finding a workable gold field.

Some sources say that Edward and Gabriel met by chance after one of these expeditions, and that Edward – ever open about his finds – told Gabriel all he needed to know in order to make his discovery. Others state that the rumour reached him indirectly. Still others insist there was no link at all.

This isn’t just a matter for historians to quibble over – it’s also a matter of justice. In 1857 the Otago Provincial Council set up a reward fund of £500 to go to the discoverer of a remunerative gold field in the province. The reward was applied for on Edward’s behalf in both 1857 and 1861 but both times the requests were brushed off. Gabriel on the other hand ended up receiving £1000 after the reward was doubled.

This begs the question as to why Edward was overlooked and Gabriel rewarded, since our sources indicate that it has always been known that Edward’s discovery came first. The easiest and most obvious answer – especially in our current times – is racism. However, the oldest sources suggest that Edward did not have the required knowledge or connections to take advantage of his discovery. This is somewhat supported by the fact that his applications to the government were always made with the assistance of another person. Alan Williams, in his history of our subject, argues that it was instead a matter of timing.

Until 1860 Captain William Cargill was the Superintendent of the Province of Otago, and as a pious Presbyterian his vision for the region did not include the sort of unsavoury characters brought in by news of gold. So perhaps he was the reason that Edward’s find was ignored in 1857 but Gabriel’s publicised in 1861.

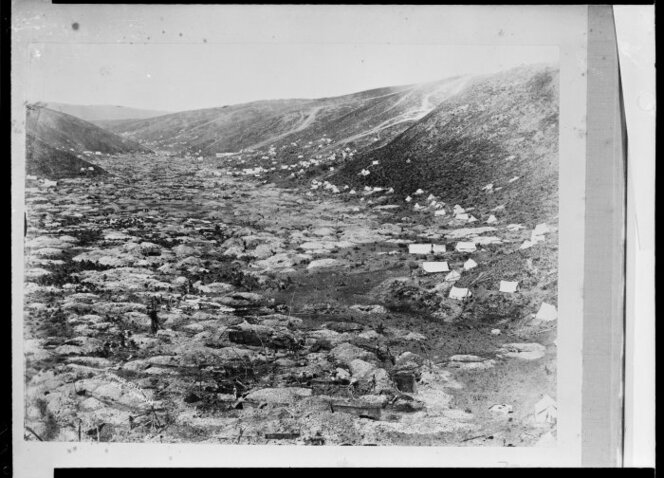

Whatever the reason, the gold rush was in full swing by 1863, presumably to the disappointment of Captain Cargill, but Edward did not take up a claim. Instead he is briefly mentioned as being a store keeper at Waitahuna Gully. Then history loses sight of him until 1885 when it then came to the public’s attention that an ageing and unwell Edward – now living in Balclutha – was on the verge of destitution.

The government was once again petitioned that he should be honoured for his discovery. Unfortunately the cold-hearted politicians decided that too much time had passed to make such a reward, and opted instead to offer 50 pounds provided that the petitioners could raise another 50 themselves.

This was promptly done and the money raised was enough to keep “Black Peter” looked after for the rest of his life. He died in 1893 and was interred in Dunedin’s Southern Cemetery.

Whether it was racism, personal circumstances, or politics, Edward Peters missed out on his rightful reward and his true place in our founding legend. It’s much too late to fix the first, but with a little work we may still be able to set the second right.

References:

OLD IDENTIANA. Otago Witness, Issue 2300, 31 March 1898

Edward Peters (Black Peter), the Discoverer of the first Workable Goldfield in Otago by Alan Williams

Unsung gold-rush hero to have his day by Glenn Conway

GABRIEL’S GULLY GOLD. Hutt News, Volume 10, Issue 6, 8 July 1936

GABRIEL’S GULLY Otago Daily Times, Issue 22048, 2 September 1933

Striking it unlucky in the gold fields by Glenn Conway, Otago Daily Times, Saturday, 11 April 2009

Images

View of the gold mining camp at Gabriels Gully, Tuapeka. Ref: MNZ-0336-1/2-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/23147843