There’s been a lot of attention in the media recently about detention camps or internment camps, how they should be defined, and the history of such places in the USA, Nazi Germany, and elsewhere. I’ve long known that the WWII Japanese internment camps were a dark blight on American history, but I rested smug in the knowledge that no such thing had ever happened on our fair shores.

My smug bubble burst when I learned that not only did we have our own Japanese internment camp but we are responsible for an incident which ended in the deaths of 68 of those prisoners. That’s a shocking event to never have heard of.

Yet, as we shall see, the path to remembrance has been long and complicated by cultural difference, prejudice and the lingering sting of old wounds.

Featherston seems a nice town. Any town with two second hand bookshops on the main street is all right by me. But on the outskirts on State Highway Two I sought out a little pull off with a haunting past. All seems fine at first, a memorial surrounded by exotic trees recalling the role of the location in the First World War as a toughening up camp for recruits. I’m not saying the whole “harden up” concept isn’t problematic for us millenials, but it’s par for the course when it comes to history.

A closer look reveals that something more is going on here. Resting on the plinth is a string of multi-coloured origami cranes, which while beautiful are a little out of place for the average Kiwi war memorial.

Investigating further, I discovered in a far corner a small memorial with a copper plaque that went some way to explaining this contradictory token.

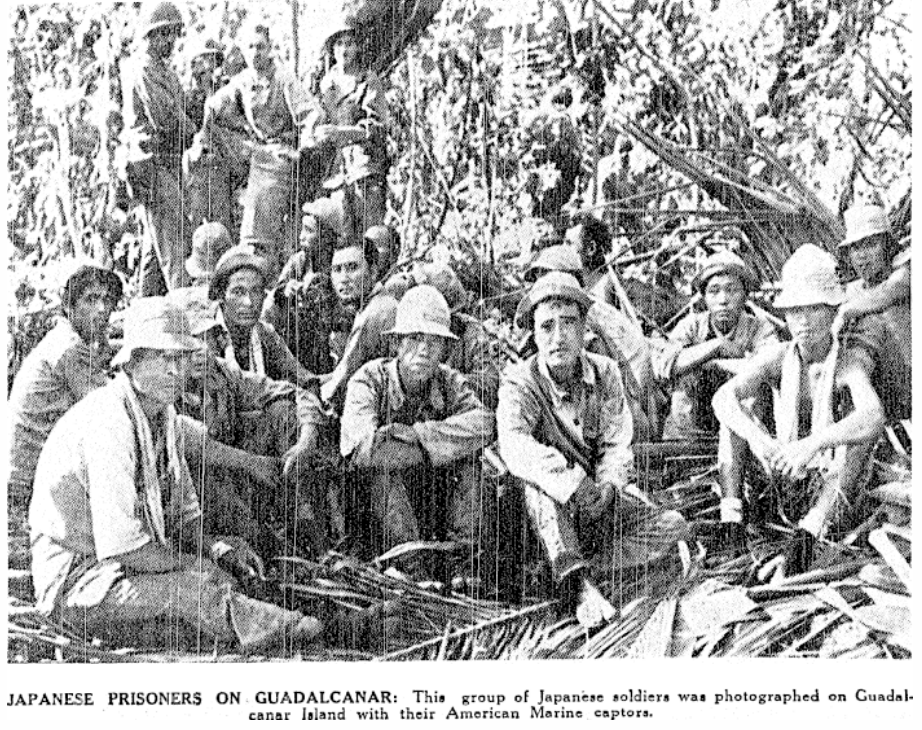

In 1942 the tide was turning in the Pacific War as the Allies launched their first major offensive against the Empire of Japan. Known as the Guadalcanal Campaign, this action aimed to wrest control of the Solomon Islands from the grip of the the overstretched Japanese.

But there was a human product of this offensive, and that came in the form of captured Japanese military and paramilitary personnel. At the request of the United States this old training camp was re-fitted as a prison camp, and 60 acres of land was closed off by barbed wire.

A total of 868 prisoners were interned here in the 1942-1943 period, about 500 of whom were members of work units while the rest were military personnel.

After an interlude on several Pacific islands, the first of the captured Japanese arrived in Featherston in September of 1942 to discover that tents were to be their only accommodation – at least until something more suitable could be constructed.

The New Zealand authorities prided themselves in adhering strictly to the Prisoners of War Convention of 1929 – otherwise known as the Geneva Convention – and our “official history” of the Second World War even pointedly states that we “erred on the side of generosity”.

But in his memoir detailing his imprisonment in New Zealand, Michiharu Shinya states that he arrived in Featherston to find the camp in an extreme state of tension.

The Geneva Convention allowed prisoners to be put to work, a requirement that the New Zealand authorities were determined to impose. Japan had not chosen to sign the Geneva Convention, and therefore many of her soldiers were unaware of its contents. The Japanese POWs were already in psychological turmoil – all their training and indoctrination had taught them to prefer death to being taken prisoner. Many considered their lives already over, believing they could not return to Japan regardless of whether they survived, and fearing the cruelties they might be subjected to while in enemy hands.

Michiharu describes his own distress at the position he was in, spending many days lying in bed in a daze, debating with himself over whether to suicidally attack the guards, attempting a slow suicide by refusing to eat and avoiding medical attention, and his self-recriminations upon discovering that no matter how had he tried, he could not overcome a treacherous will to live.

He says of the work requirements that to the Japanese:

…such a thing would go beyond all that was proper. Of course the work itself was not important, but it was the question of honour. It was an issue based on the difference between culture and traditions, a point which the New Zealanders were completely unable to understand.

The POWs at Featherston were divided on the issue – some advocated rioting and resisting until all prisoners were dead (including one group known by the since-ruined-by-a-movie moniker of ‘Suicide Squad’), some preferred stubborn refusal to work, still others were willing to accept that they had no choice and reluctantly do as required. The paramilitary prisoners were much more inclined to go along with what was requested, but the captured soldiers simply couldn’t countenance working for the enemy.

The Kiwi prison guards and commanders at the camp had little notion of what was going on in their captives’ heads. They were pulled from reservists considered unsuitable for overseas service, and received no special training for this delicate job.

In Western culture there was no shame in surrendering when faced with overwhelming odds, or with being taken prisoner. Combatants had an understanding that POWs were due certain standards of treatment and expected hostile powers to adhere to these. But the convention said that prisoners could be required to work, and they saw no reason that the Japanese should be exempted from this.

On 25 February 1943 matters came to a head. One of the compounds refused to send out a work party, and instead about 240 prisoners gathered in the yard and sat cross-legged while two officers who had joined them demanded a meeting with the camp Commander. Instead of giving in to this demand, the Commander sent 47 soldiers to take up positions around the obstinate prisoners, demanding the officers return to their own compound and the rest of the prisoners make their way to the assembly ground. They managed to forcibly remove one of the officers, but attempts to remove the second only escalated the tension.

What happened next is not entirely clear. It seems the adjutant fired a warning shot – and either that or a second shot wounded the protesting officer and killed a second prisoner. This incited the mob to action – our official history says they rushed the guards, others suggest they threw rocks.

Yasuhiro Ota’s study of the event, based on eyewitness accounts, suggests that the first guard to shoot did so without being ordered. This soldier’s brother had been killed in the Tarawa Incident, in which 17 New Zealanders had been cruelly executed by Japanese troops, perhaps explaining why he may have panicked. Accounts indicate that this may have been the soldier whose friendly fire wounded some of his colleagues.

The official history states that the soldiers fired for only 15-20 seconds before being ordered to stop, and when the dust cleared it was found that 48 prisoners were dead and 74 wounded. One New Zealand guard was killed and six others wounded by ricochets.

In a twist quite astonishing to the Japanese, who had expected this event to end in death or execution, their wounded were removed to hospital where they not only received good care, but were visited by supportive Featherston locals who sought to bring them comfort. Michiharu Shinya, though not involved in the incident itself, describes such acts of kindness from his enemies as playing a huge part in breaking down his resistance.

The Prime Minister of the time, Peter Fraser, made a brief announcement regarding the incident, but otherwise sought to cover it up as much as possible, fearing reprisals against Allied prisoners of the Japanese. To some New Zealanders, this was the first they’d learned of the Japanese being interned on our soil.

The subsequent inquiry highlighted the lack of cultural understanding at play (although the original report which accepted some responsibility on the New Zealand side was edited at the behest of Britain to portray the Japanese as wholly at fault). Efforts were made to improve conditions – the tents were replaced by pre-fabricated buildings known colloquially as “dog boxes”, greater efforts were made to provide a more familiar diet, and cultural exchange improved with English lessons and a visiting pastor, while the prisoners occasionally made gifts for the New Zealanders they came into contact with.

The issue of work seemed fairly settled from then on, with a 33-hour work week being imposed. The Japanese worked at carpentry, gardening and stone crushing.

No further incidents occurred, and when the war ended in 1945 the prisoners were returned to Japan, sometimes to families who had already mourned them as dead. For both sides now it was time to move on and time to heal…but the road to that destination would be long and filled with pitfalls and prejudice.

The story of that journey will be told in part two of this series, but for now let us take this moment to behold the summer grass and reflect on the dreams of warriors.

References:

Prisoners of War. Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War by W Wynne Mason

The “Peace Gardens”, Featherston, South Wairarapa and The Chor-Farmer by Yukiko Numata Bedford

Beyond Death and Dishonour: One Japanese at War in New Zealand by Michiharu Shinya

Shooting and friendship over Japanese prisoners of war by Yasuhiro Ota

Hello – where can I find part two of this series, please?