Family road trip ahoy! What better destination than the famous Old Man Rock, overlooking the wilds of Central Otago?

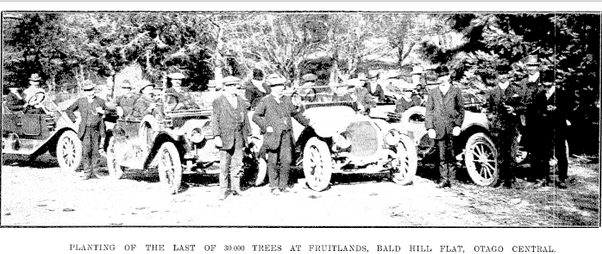

We first travelled inland to the locality of Fruitlands. Previously known as Bald Hill Flat, it was given the more attractive name when 40,000 fruit trees were planted there in the early 1900s. Alas, lack of sufficient water and an inhospitable climate caused the scheme to fail, and by 1930 most of the orchards had been pulled up and replaced with pasture, leaving only the name as a reminder.

We turned off up Symes Road and entered the Kōpūwai Conservation Area, beginning our climb up the Old Man Range. You may not guess by looking at it, but in fact we were climbing the flank of a long-dead giant. The first humans to settle this region were Te Rapuwai, and to them fell the responsibility of clearing out the monsters who inhabited this wild land.

They learned of Kōpūwai and his pack of fearsome two-headed dogs from a woman named Kaiamio, the sole survivor of a hunting party. Kōpūwai had kept her prisoner in his cave, but she was determined to escape. The ogre would only let her outside to fetch water, but tied a cord around her wrist which he would tug every so often to make sure she was still there. Secretly, she built a raft from raupo, then made her escape down the river, tying the cable to a bunch of reeds, which provided just the right amount of resistance to trick the monster into thinking he still had her.

Kōpūwai, when he discovered this, was so angry that he drank up the entire river. Perhaps that’s why Fruitlands is so dry.

Hearing this story, Te Rapuwai resolved to kill the giant. He took his men went to his cave while the dogs were away and the monster was sleeping. They lit a fire at the entrance, beating him to death when he tried to escape. Dying, Kōpūwai became the Old Man Range, and his dogs also turned to stone where they were ranging in the Waitaki River valley.

It wasn’t long before we found the estate of a bold few who tried to build a life on Kōpūwai’s shoulder, long after the giant was subdued. Overlooked by yellow mountaintops and snuggled among schist outcrops is a little house – Mitchell’s Cottage.

A premier example of the stonemason’s craft, it is perhaps also a good example of a labour of love, for it was built by Andrew Mitchell for his brother and sister-in-law, John and Jessie Mitchell.

The two brothers hailed from the Shetland Isles, which is where Andrew learned his craft. Like many gold-seekers, he first worked the Australian gold fields before joining the rush to Gabriels Gully. When that too dried up, he moved north, and in the 1870s finally found the gold he sought in Kōpūwai’s frozen veins.

It soon became a family affair as he asked his cousin James White to join him.

James Mitchell, meanwhile, arrived in New Zealand around 1872 and first settled in the Skippers/Macetown area where he met his wife, Jessie. Some time in the 1880s he joined his brother here, bringing a corrugated iron clad building all the way from Skippers and erecting it near the future site of the famous cottage.

Andrew completed the 5-room stone house by 1904, and just as well, for the couple needed the space to house their 10 children.

Out the back are a few outbuildings, cleverly incorporating the hulking tor behind, one door leading to a laundry. I have to salute dear old Jessie, who presumably did the laundry for her 10 children with this as her only amenity!

Round the corner is the chicken coop, and up the hill is a path which takes us up to a boulder with a sheer face and many vertical ridges drilled into it, one of the places from which Andrew gathered his stone. Back down the hill and along the other side of the huge tor at the rear of the house, we found another small stone structure – the cool store.

On the slope below the house is a convergence of stone walls sheltering an outhouse and a small cluster of introduced trees – holly, poplar, spruce and rhododendron – a little glen of European harmony in this harsh land.

Having fully explored the cottage (mostly at my insistence) we were back on the road again and quickly discovered Kōpūwai’s lower reaches are positively hospitable compared to his higher slopes. The grass grew gold, punctuated with patches of speargrass and looming rocks, while the road became ever more gnarly.

This is the land that Andrew and James, and his cousin John White worked. In fact, we spotted another example of Andrew’s masonry down the slope – White’s Cottage, which gained its own little historic reserve in 2017.

The work of extracting gold from these slopes was troubled by the same issue that killed the dream of Fruitlands – lack of water. To reach White’s Reef, the cousins had to build a water race over 9km long.

Andrew doesn’t seem to have built a homestead for himself, perhaps because he remained a bachelor all his life. He was a miner until his death in 1905, when he was fondly remembered as a pioneer settler who would happily walk to Alexandra and back whenever the need arose (they sure did walk in those days!).

Speaking of walking, here’s an excerpt from a 1928 article regarding the difficulty of reaching Old Man Rock:

At last a fair lady appeared who had been there, and her advice was as comforting as her appearance. The trip, we were assured, could be made in three hours by horseback. That decided us. If it took horses to get a woman there, we could use Shank’s pony.

Rude guy

Rude.

Finally we made it to the summit, bare and rocky, and emerged from our vehicle into a chill, whipping wind that threatened to freeze us if it did not first blow us away, and we stared up at the landmark described in 1897 as:

A monument not made by hands

In solitude sublime.

Sprung from the depth of ages past,

And on through future ages last —

A sentinel of Time.

MINER

Imposing though it is, adventurous souls have nevertheless aspired to conquer it.

The earliest account I can find of someone climbing the rock is from 1879, when a surveyor known as “Mr W D B Murray” reached the summit. By his account he was tasked to make the Old Man Rock a boundary, and was quite determined to do so.

His strategy was as simple as it was clever – Mr Murray tossed a weighted line over the top of the rock, which he used to pull up a thicker line, and finally a thick knotted rope. He was then able to ascend the rock and fix an iron bar on its summit, thus transforming it into a trig station.

After this, it became a bit of a tradition to leave a half-crown piece on the rock as a mark of a successful climb. I cannot tell you whether any remain, as I did not make the attempt myself.

We could only stand a very short time in the weather before we fled downhill to more welcoming climes. Behind us, Kōpūwai slept on and the stony sentinel once again donned its cloak of solitude sublime.

References:

WHERE ORCHARDS FAILED Evening Star, Issue 20015, 5 November 1928, Page 16

The Welcome of Strangers: An ethnohistory of southern Maori A.D. 1650-1850 by Atholl Anderson

Mitchell’s Cottage, Outbuildings, and Sheepfolds

Conservation reserves extended extra 1200ha by Pam Jones

Obituary. Alexandra Herald and Central Otago Gazette, Issue 484, 23 August 1905, Page 4

THE OLD MAN ROCK. Tuapeka Times, Volume XXVIV, Issue 4412, 16 January 1897, Page 4

THE OLD MAN ROCK Alexandra Herald and Central Otago Gazette, Issue 1630, 11 April 1928, Page 5

THE OLD MAN ROCK OR OBELISK Otago Witness, Issue 3823, 21 June 1927, Page 6

Overseas Mail Otago Daily Times, Issue 22750, 10 December 1935, Page 8

What was the original name of the locality that later became known as Fruitlands, and what led to the failure of the fruit orchard scheme in the early 1900s?

Visit us telkom university

Remember, adventure can be found anywhere, even in your own backyard. Take a walk in a new park, explore a hidden alleyway, or strike up a conversation with a stranger.