Today I teamed up again with KL’s Self Discovery as we seized the opportunity to visit Otago Harbour’s iconic Quarantine Island. The occasion was an open day hosted by the Quarantine Island/Kamau Taurua Community during which we would be able to explore the island and attend a talk by Otago University’s Barbara Brookes about the treatment of soldiers confined to the island due to contracting venereal disease.

We gathered at Back Beach at 10am to meet the boat that would take us across. The morning was calm and clear – perfect conditions!

We gathered at Back Beach at 10am to meet the boat that would take us across. The morning was calm and clear – perfect conditions!

Then we loaded into the boat and chugged past Goat Island to land at the small dock below the lodge. We were greeted by a friendly community member beneath the wooden welcome arch and then left to our own devices.

First order of business was of course to investigate the two decaying ships on either side of the dock. On one side is the rusted steel remains of the Waikana, one of two ferries purchased by Bob Miller who leased the Island between 1925 and 1932 to bring excursionists (and their money) to the Island. Bob was a savvy businessman who made the most of every resource that fell into his hands, but he was hit hard by the depression and eventually unable to pay his rent. He was replaced by two brothers who also could not make the island viable.

An attempt was made to break up the hulk around 1960 as part of an island tidy up effort, but she did not surrender easily, so her remains were once again left to the weather.

On the other side is the wooden Oreti, a steamer built in 1902 in Australia. She had a career first in the North Island and then as a timber carrier in Dunedin before Bob Miller bought her for scrap. She was rather more thoroughly dismantled in 1960.

Having investigated the hulks to our contentment, we made our way up the path to St Martin Lodge. Somewhere in here amidst the extensions added by Bob Miller is the house which was occupied by the Dougall family who were caretakers of the island back when it was a quarantine station. Now it can sleep up to 30 people as a home base for visitors to the island.

We passed by, scored a complimentary cup of tea, and continued past the current caretaker’s house to admire the newly-restored married quarters. This is the one remaining wing of the old quarantine buildings built to hold passengers being held at the island. There was once a second wing to house single women, joined to this one by way of a kitchen, from which a mess hall also stood at a right angle. The single men were exiled to nearby Goat Island to prevent any hanky-panky. Each of the wings contained 24 rooms divided between two floors, holding as many families or ninety-eight single women.

This building also featured in another of Bob Miller’s schemes. He ripped out the interior dividers and converted it into a dance hall. With the restoration nearing completion perhaps it might once again be used for this purpose!

Near the married quarters, on a little headland looking out towards the mouth of the harbour, stands the iconic sail shaped island chapel.

This chapel was proposed by the Quarantine Island Community in 1960, back when it was still the St Martin Island Community, full of dreams of converting the island into a retreat for work and worship. Building of the chapel was fraught with many delays, and the chapel was not formally opened until 1972 when it was named the Knudson Chapel in honour of Trevor Knudson, a vital member of the Community who was killed in an accident while working on the island.

This chapel was proposed by the Quarantine Island Community in 1960, back when it was still the St Martin Island Community, full of dreams of converting the island into a retreat for work and worship. Building of the chapel was fraught with many delays, and the chapel was not formally opened until 1972 when it was named the Knudson Chapel in honour of Trevor Knudson, a vital member of the Community who was killed in an accident while working on the island.

By then it was getting close to 11am and time to gather in the lodge for the lecture we had come to see. The little room was packed to capacity, once again surprising me with how enthusiastic we Dunedin folks are about our history. Barbara was introduced by Lyndall Hancock, indispensable 85-year-old member of the Quarantine Island Community and author of A Short History of Quarantine Island, the culmination of 46 years of research. Said short history being 218 pages long, you can imagine just how much I’m glossing over to fit what I can into one readable article! The book is well worth a read and available from the University Book Shop or Dunedin Public Library.

Barbara took the stage and related the sorry tale of those ANZAC soldiers who were sent to this island in secrecy beginning in March 1915. They were men who had been found to be suffering from venereal diseases such as syphilis and gonorrhea, exiled here for treatment while their families were cryptically informed they were “in hospital”. At the time diagnoses of such diseases were met with moral condemnation and horror – rumours flew that they could be transmitted via towels and even through grass surrounding isolation camps. Life on the island carried a flavour of punishment, with few entertainments and regular military drills. If any needed to be transferred to Dunedin hospital they were housed in the oldest ward with the fewest comforts and only allowed outside under armed escort.

In 1917 they were forbidden from marching in the city’s ANZAC parade, and so raised their own flag on the island as a form of protest.

The deplorable attitude towards these unfortunate men was amply demonstrated when another group of soldiers had to be quarantined with smallpox – while the VD sufferers were hastily removed to a barracks and prison at Taiaroa head, the new group was showered with media attention and public donations. At least the VD sufferers were able to take advantage of some of the gifts (such as a piano) once the time came for them to return to the island.

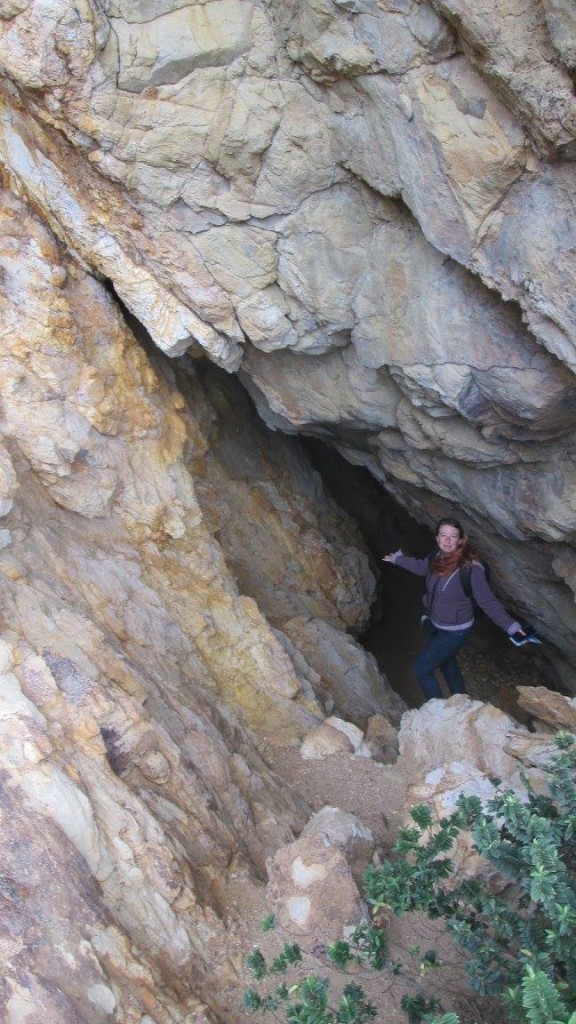

Leaving the lodge, we stopped briefly for lunch, then embarked on a circuit of the island. This took us past reforestation efforts (a struggle in such salty and windswept conditions!) and into the native bush at the western end of the island. Our brochure advertised an “energetic” detour down to Te Ara, the local cave, so I led KL down the steep slope.

It was a bit of a surprise when we were presented with some ropes to cling to as we scrambled along a near-vertical cliff face, but we made it in the end.

Then it was through the surprisingly large cave and out the other side. A dreadful pong drew our attention to some members of the shag colony sunning themselves on the rocks nearby.

When we turned our focus to the path back up the hill, we finally understood “energetic” to mean “involves climbing a sheer cliff face”. As we struggled slowly upwards I marvelled at the fact that I can somehow still convince people to follow me into these situations.

When we once again reached the main track, we collapsed to rest for some time, assuring each other that it was only to admire the view of Goat Island next door. Eventually we worked up the courage to set off again and continued around the headland. We emerged from the bush and passed above another scenic little bay.

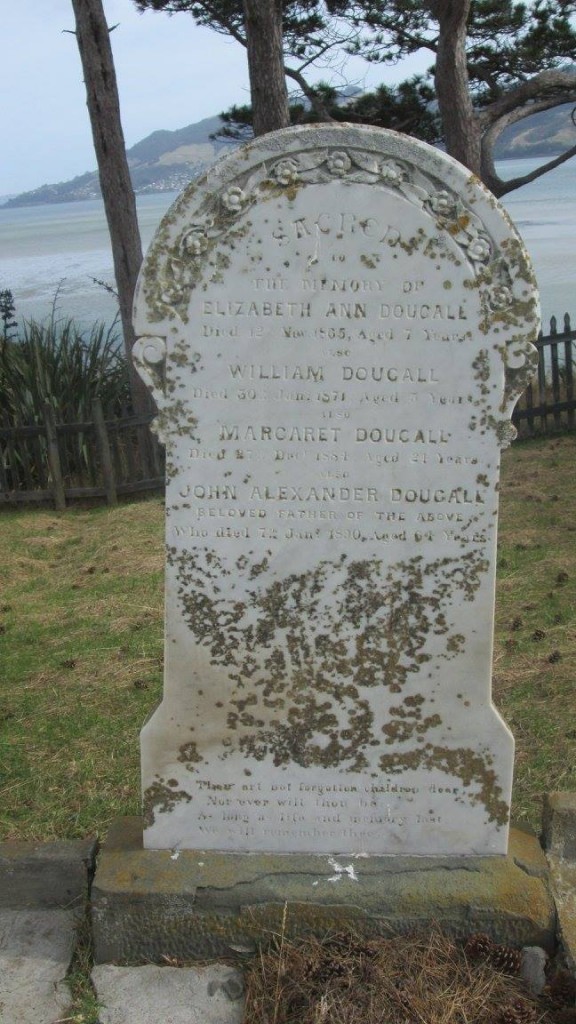

At the far end of the bay stood the little picket fence that surrounds Quarantine Island’s lonely cemetery.

There have been 72 burials in this cemetery, with over half of them being children. Only two headstones have survived, all the wooden grave markers having been lost over the years. Still visible however are many mounds crowded together, indicating burial sites.

The smaller of the remaining headstones lies broken in the middle of the field. We were unable to read the worn text, and small wonder because it is in Italian. Translated, the somewhat misspelled inscription reads “In God here lies the baby son of Nicola and Susana Azzereti. Born and died 27 October 1875”. The date doesn’t seem to indicate a quarantine-related death, but it’s possible that this baby was born to non-quarantined passengers within the harbour bounds, who could not afford burial elsewhere.

I would like to know more about the story of this family.

The other belongs to the Dougall family, who lived on the island as caretakers of the land and its quarantine buildings for three generations from1863 to 1924. They were all, men and women, experts at boating. The first of the family to arrive here were John Alexander and his wife Elizabeth Dougall, bringing with them two young daughters. It’s unknown how Elizabeth Ann, their eldest daughter, met her end at only seven years old, but their third child William fell victim to scarletina (scarlet fever) brought by the Robert Henderson in 1870. Remember the Robert Henderson, because you will meet her again in a future post

Another daughter, Margaret, caught typhoid fever from the Corona in 1876 but recovered only to pass away eight years later aged 24. The children’s father suffered a stroke five years after that and was interred here with the children he had lost. He had kept the island for 27 years, leaving two daughters and one son behind to mourn him.

His widow continued the family work, helped by her youngest child who was named John William after his deceased older brother but known as Will. Will later took over the work entirely when his mother retired and raised his two daughters on the island.

We left the poignant little cemetery and continued to the site of the second hospital, where quarantined patients who were actively ill were sequestered on the other side of the ridge from the healthy island residents. All that remains now is the fireplace.

The crest of the ridge brought us to the parade ground, a flat spot levelled by the men so poorly treated during WWI. This high spot was blustery and unpleasant, in stark contrast to the sheltered lower reaches. I wonder if that was intentional.

Here too stands the simple memorial to five local soldiers who were court martialled and executed. 28 New Zealand soldiers were sentenced to death during WWI, mostly for desertion and mutiny, or “extreme saneness” as the supplied brochure aptly puts it.

Eight paving stones nearby represent the men in the firing squads. Forced to shoot their own men, they were also victims – a sad reminder that war has ways of destroying the humanity of all who are caught up in it.

We left the bleak place and headed back down to the little cluster of buildings and the warm hospitality of the Quarantine Island Community. The visit had been an education for us both. Many thanks to Barbara, Lyndall, and the rest of the Community for sharing with us the history of this very special place.

References:

A Short History of Quarantine Island by Lyndall Hancock

Years of research for Quarantine Island book by Bruce Munro

QUARANTINE SOLDIERS Wairarapa Age , 12 December 1918, Page 5

Assorted brochures provided by the Quarantine Island Community

Me again! I managed to live in Dunedin for my first 20 years and never gave Quarantine Island a thought. Now, many years later, I have my maternal grandfather’s war record and aside from being shot by shrapnel and gassed three times (can you believe such bad luck?) he also contracted VD – probably in Egypt where the boys languished prior to being shipped to Turkey and other European killing fields. He spent quite a time in a VD hospital before being shipped home due to the gassings in 1917. Your story made me wonder if he was ever on this island? Naturally, given the “moral condemnation” of the times, his VD was never mentioned, although his PTSD certainly got an airing from my mother whenever his name was spoken!

Not sure if I will ever be able to find out if he was on the island, as I now live in Scotland and come home only every couple of years and very rarely reach Dunedin. He was a Dunedin boy and returning from WW1, lived in various parts of Central Otago for the most part.

Love your stories!

S.

Wow that’s certainly very interesting. I don’t know if there’d be any record of your grandfather being on the island as they certainly kept things very quiet. But it does make you wonder if he was one of the unfortunate men exiled to the island!

Hi.. I’ve just read your blog while I was looking for a photo of Baby Azzariti’s gravestone. Nicola and Susana Azzariti were my great-grandparents, and Baby Azzariti my Great-grand uncle. Nicola was from Naples and Susana originally from Ireland.. I believe Nicola met Susana in Australia on his way to New Zealand. Their daughter Felicia married my great-grandad Henry Steele Montgomery. After the loss of their baby son Nicola and Susana successfully settled in Port Chalmers and later Dunedin. I love your words “Memorial to a little boy who died before he lived”. As a family we feel the loss of this tiny boy and we would dearly love to see his gravestone preserved. Many thanks for publishing this..

Thanks Linda for the extra info, an interesting couple for sure! I’m glad to hear they settled successfully after the loss of their poor baby boy.