This is part 2 of a series on the history of Niue. Find part 1 here.

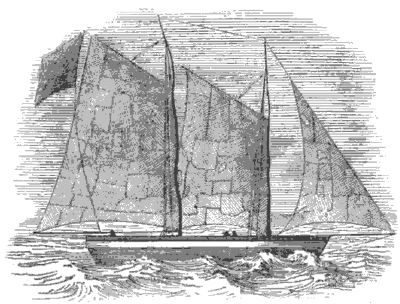

In 1830 the flagship of the London Missionary Society – the Messenger of Peace – sailed for a tiny island with a gruesome reputation. On board was missionary John Williams, and he had his sights set on saving the souls of its inhabitants.

Niue’s famous resistance to outsiders posed a bit of a challenge, but the LMS had specially adapted its strategy to the Pacific environment, often leading with native Polynesian teachers to soften the cultural impact and get a foothold in the community. This was John’s plan, to drop off two Cook Islanders with their wives, but though the four spent a short time ashore, they were too frightened by the fearsome Niueans to stay.

So John turned to Plan B. I’ll let him explain:

“We tempted two youths to stay on board by holding out to them fish hooks and pearl shells, articles they hold in great estimation. And while gazing at the wonders they saw we sailed away with them.”

The two men, Niumaga and Uea, were understandably very upset, and spent the voyage terrified that they would be killed or even eaten, as John observed that they mistook the pork eaten by the crew for human flesh.

They spent several months with the missionaries in Samoa, Rarotonga and the Society Islands before finally being dropped off back to Niue. Initially their families rejoiced but when their return was followed by an outbreak of disease, Uea and his father were killed. Niumaga managed to escape, hitching a ride on a passing whaler, and ended up back in Samoa.

John Williams was killed on Erromango in Vanuatu in 1839, a year before the next LMS attempt to get a foothold on Niue.

In 1840 the Reverend Archibald Murray employed the assistance of a Niuean called Liulauvi in the hopes of successfully landing his Samoan mission teachers. The visiting Reverend received a lot of interest from the island’s residents, though it was trade goods that interested them, not spiritual enlightenment. The crew were so intimidated that they purchased a large amount of weapons just to disarm the visitors.

Liulavi, after communicating with the people of his home village, became steadfastly opposed to landing. The answer was the same in every district – any outsider who attempted to land would forfeit their life. Any village that chose to protect them would be subject to the hostility of its neighbours.

Archibald Murray left Niue disappointed, carrying his spurned mission teachers, a massive quantity of weaponry, and three Niueans who had come aboard. It’s unclear whether this time they were voluntary passengers – one died almost immediately upon arrival in Samoa, one hitched a ride away in a passing whaler, and the last became a member of the church. Taking the name of Paulo he lived until 1852.

The LMS’s big breakthrough came with the return of Niumaga to Samoa some time in the 1830s. With him was another Niuan, Nukai. The newcomer was taught to read and write, and baptised as Peniamina.

Finally in 1846 Peniamina was able to land at Mutalau. Though he was not officially a mission teacher and the LMS missionaries had some doubts about his loyalty to the cause, he managed to pave the way for the acceptance of Samoan teachers. Today if you follow a rough trail into the rainforest at Mutalau, you can still find the limestone outcrop or “fortress” where the warriors of that village protected him from those who remained hostile to his presence.

Within three years Peniamina’s efforts had paved the way for the arrival of the first Samoan mission teacher, Paulo, to land at Mutalau. Over the course of the next decade great changes occurred on the island. The number of Samoan teachers increased to five, and soon people were able to travel without fear between the previously hostile districts. The constant warfare between rival villages was transformed into a more peaceful but no less intense competition over who could boast the best chapel, best teacher, or raise the most funds for missionary purposes. This strong sense of regional identity and competition still exists on Niue today – just look at any village open day.

Unfortunately the British Empire was about to return, and in doing so would endanger the three decades of delicate work of the LMS in gaining a foothold here.

In June 1852 the ship Legerdemain was wrecked on a reef to the southeast of Niue. Thinking quickly, the passengers and crew built a raft which when combined with three boats from the ship enabled them to set out in search of land.

Land they found, but it was the east coast of Niue, hostile in more ways than one. They could make no landing on the rugged coast, and the locals – as yet not swayed by missionary influence – took the opportunity to loot their belongings and send them on their way.

Rumour spread that Europeans from the wreck were being held prisoner on Niue, and captain of the Brithish Royal navy’s HMS Calliope Sir Everard Horne set off with his crew to investigate. What happened when he arrived off the coast of Alofi on the west coast (notable for having very little to do with the people on the eastern side of the island) was much disputed and remains unclear to this day.

The official Calliope record claims that when the Niueans came aboard to barter the crew noticed some unusual European items on offer, so they seized 17 men and a chief to be kept as prisoners until the white men were produced. After three days of attempting to get their demands across without the help of an interpreter, and the Niueans failing to produce the prisoners that they did not have, they released the prisoners, gave the islanders a stern warning, and departed.

The missionaries of the LMS heard a rather different story when they returned to check on their resident mission teachers. They were told that the Calliope had destroyed some of their vaka in the process of taking prisoners and had fired upon those in the water, causing one to be drowned.

When the prisoners were ‘released’ they had in fact been thrown into the water far from shore, and only three made it back to friendly shores. The others may have been drowned at sea, but the Alofi people also suspected they may have come ashore at Avatele and been killed by the people there. On that basis they made an attack upon the southern village and killed three people there.

Of those three who had returned to shore, one was killed by his own people, supposedly for stealing from the Calliope and creating all this misery. Lastly, the wife of one of the drowned captives committed suicide in her grief.

The LMS declared that in consequence of the Calliope’s disastrous visit 15 lives had been lost, conflicts had been roused on the island, and delicate mission work had been compromised. Unfortunately by the time they were able to make their criticisms public, Sir Everard Horne had died and was unable to respond to the accusations.

The first permanent European missionary arrived at Avatele on 20 August 1861 – William George Lawes who came with his wife Fanny. This time the people welcomed them and they were soon settled in comfortably.

But there was new trouble on the horizon, this time in the form of ships prowling the Pacific in search of labourers for Peruvian plantations – and they didn’t care if said labourers were willing, often employing coercion and trickery to lure their victims into the ship’s hold. Though the entire operation only lasted about seven months, this event was one of the most devastating to ever hit the Pacific. The victims could scarcely conceive of such a heinous crime, and whole communities suffered “demographic collapse” after families were decimated. The fate of those “recruited” was arguably worse, as we shall see.

In December 1862 one of these ships, the Rosa Patricia, called at Avatele. As usual the locals paddled out with trade goods but once on board they were ambushed and forced into the hold. The ship then moved on to Mutalau and repeated the process, although a small number of those captured at Avatele were able to escape here. Then the slave ship departed, leaving confusion and grief in its wake.

In March 1863 the Rosa y Carmen arrived and although trading with offshore vessels had been forbidden there were still those willing to take the risk. This time 19 men were taken – leaving 83 widows and orphans behind.

The Rosa y Carmen was in the grip of a dysentery outbreak when she called at Niue, and this combined with a shortage of food and water on board meant that many of her passengers were dead before ever reaching Peru. One historian called it “the worst voyage in the history of the labour trade”. Conditions on the Rosa Patricia were only somewhat better.

Upon arrival they found themselves slaves in every practical sense, though officially they were classed as ‘colonists’. In that alien environment they died at an alarming rate, deaths attributed to lack of immunity, overwork, mistreatment, ‘melancholia’, loneliness and loss of will to live.

Only one man out of those taken from Niue ever returned. In fact, while over 3000 Pacific Islanders in total were ‘recruited’ for Peru, only 257 of those survived the ordeal.

It had become abundantly clear that Niue could no longer protect herself from the outside world, and so the choice was made to turn to a higher power for protection. For this they formally petitioned the British Empire, once in 1887 and again in 1895.

After much stalling the Empire would finally heed the call, but not quite in the way the Niueans intended. This answer would bring our own New Zealand into the story, as we shall discover in part 3 of this series.

References:

NIUE 1774-1974, 200 years of contact and change by Margaret Pointer

SAVAGE ISLAND OR SAVAGE HISTORY? AN INTERPRETATION OF EARLY EUROPEAN CONTACT WITH NIUE by Sue McLachlan

Slavers in Paradise by H. E. Maude